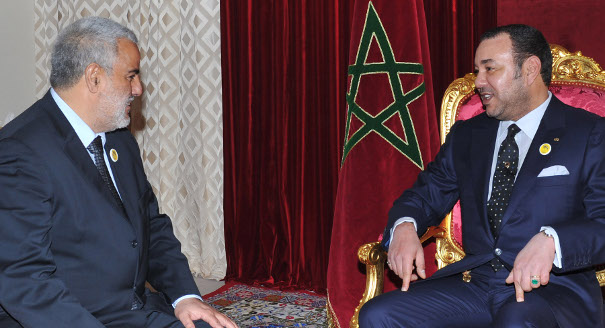

Prime Minister Abdelilah Benkirane and the Islamists of the Justice and Development Party (PJD) have been butting heads with the palace since last November. Some conflicts with King Mohamed VI have been subdued, but others are in the open outright. Among the most important was this past March’s crisis: Mustapha El Khalfi, the minister of communications, attempted to launch the media reforms that his party had promised its voters, resulting in a clash with palace officials over what has traditionally been royal oversight of television and radio. The most recent scuffle, however, came at the end of August. At a gathering of youth that took place from August 26 to September 1, Abdelali Hamieddine, a young PJD leader specializing in political and legal studies, suggested that the king did not adhere to the July 1, 2011 constitution of enacted by the popular protests of that year. He noted that while the document maintains the king’s exalted positions as supreme commander of Morocco’s armed forces, the country’s sovereign representative abroad, and the “commander of the faithful,” the new constitution gives 70 to 80 percent of executive powers to the head of government. Hamieddine argued that there is no need for the king to encroach on the prime minister’s jurisdiction.

Hamieddine's unusually sharp statement is only part of a broader crisis currently underway between the palace and the PJD, which has headed the government since receiving a plurality of seats last November. The current crisis—though long festering—was likely triggered by the king’s August 9 meeting with the ministers of interior and finance, security officials, and high-ranking military officers, all without the knowledge of the prime minister. During this meeting, the palace publicly announced it had decided to open investigations against police and customs officials in Tangiers and other ports in northern Morocco on charges of bribery and the mistreatment of migrants. The announcement was promptly followed by the arrest of some 130 government employees—a rare event despite the corruption plaguing northern Moroccan ports for decades. PJD hawks, including Hamieddine, saw the royal initiative as overstepping the palace’s authority and violating the law—insisting that the prime minister is the only authority empowered to give orders to the other ministers. The palace reacted to Hamieddine’s pointed statements by banning a PJD event in Tangiers where Prime Minister and PJD Secretary-General Benkirane, was to deliver a speech. Thus, the head of state banned the head of government from speaking, using the local authorities of the ministry of interior to do so. The minister of interior is, at least in principle, supposed to be an ally of the Islamist party.

Since the early 1960s, the Moroccan political model has always functioned with the king in the dominant role while other legal institutions have been more or less negligible. The new political reality imposed by the Arab Spring put the monarchy on the defensive and made it look for new allies to expand its support base, and in the end, it found Benkirane as an invaluable tactical collaborator. Yet with the youth protest movement weakening and internal conflicts among the February 20th Movement’s secularists and Islamists simmering—to say nothing of the movement’s infiltration by intelligence agents, the survival of other monarchies in the region and their comparative stability—the monarchy’s confidence in itself seems to have been restored. As a result it appears to be returning to its old ways of directly exerting authority without regard for the constitution. This new crisis highlights the prevalence of two fundamental, interlinked issues: corruption and the struggle for power.

Although the new constitution can be interpreted as more democratic than its predecessors, it is also more ambiguous. Its authors were crafty enough that the text, despite its democratic overtones, can be given a more opportunistic reading if the balance of power permits. Many of the skirmishes between the PJD and the monarchy stem from this deliberate ambiguity, and the climate of mistrust between the political players is only enhanced by Mohamed Al-Touzi’s (one of the members of the committee that wrote the constitution) claim in August that the constitution the committee submitted to the king is neither the version which the sovereign proposed to the public nor the version published in the official gazette.

The PJD’s powerful election campaign focused on what it deemed financial corruption, political corruption, and the rentier economy which benefits the ruling elite—including those close to the monarchy. During the first weeks of the new Islamist government, which the press mocked as “half-bearded,” some ministers wanted to uphold their campaign promises to expose some of the rentier economy practices which are at the heart of the traditional political system. This alarmed the influential elite—including some representatives of the parties loyal to the palace within the ruling coalition—who considered their Islamist colleagues’ behavior to be populist. Then the Islamist Minister of Justice Mustafa Ramid, a PJD hawk whose appointment set off the first crisis between Benkirane and the palace, made the risky decision to open investigations against two figures close to the monarchy: the former minister of finance Salaheddine Mezouar and the current treasurer Noureddine Bensouda, citing financial documents published by the press as sufficient evidence of their corruption. This move clearly upset relations between the palace and the PJD.

In this atmosphere, and in an attempt to allay fears of a witch hunt, Benkirane told Al Jazeera “God has pardoned what is past” (Qur’an 5:95), thinking that this would alleviate the royal pressure on him. But Benkirane did not take into account that the palace would turn his statement against him, and show its own will to fight corruption by arresting dozens of police and customs officials. Benkirane, who sought a moderate, conciliatory stance, was instead blasted by pro-regime media for his inaction in confronting corruption—all the while, of course, praising the monarchy’s own move.

The irony here is that fighting genuine, large-scale corruption in Morocco isn’t really on the agenda of either the palace or the government: it is so deeply entrenched in the state that an actual attempt to uproot it could uproot the regime itself.

Maati Monjib is a political analyst and historian. He is the editor of Islamists versus Secularists in Morocco (2009).