Every week a selection of leading experts answer a new question from Judy Dempsey on the foreign and security policy challenges shaping Europe’s role in the world.

Ian BrzezinskiSenior fellow at the Atlantic Council

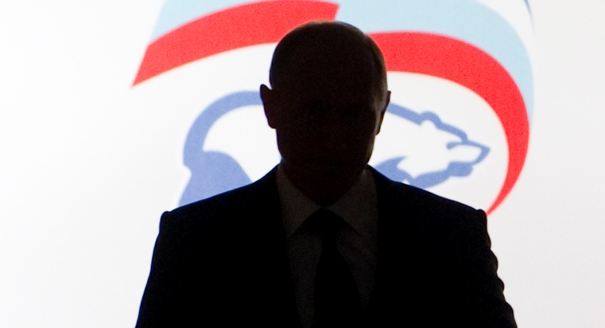

If Russian President Vladimir Putin’s provocative territorial grab in Ukraine is to be reversed, more than Europe will have wake up. The transatlantic community as a whole will have to demonstrate the commitment necessary to make Russian forces return to their barracks.

NATO, U.S., and EU leaders have warned of grave consequences for Russia should it continue its incursion into Ukraine. Some have suggested economic and political sanctions, including Russia’s expulsion from the G8 group of industrialized nations, suspension of trade negotiations, and the freezing of Russian corporate assets.

Yet, the West still balks at taking even defensive military actions that would reinforce Ukraine’s security, reassure NATO’s Eastern members, and complicate Russia’s military planning. Such actions could include mobilizing NATO’s rapid-reaction Response Force, deploying defense assets to Central Europe and the Black Sea, and providing security assistance to Ukraine.

Economic and political sanctions are necessary but unlikely to be sufficient to compel Putin to reverse course. He has surely concluded that he can ride out those consequences, just as he did after invading Georgia in 2008. Meanwhile, if NATO limits its role in this crisis to consultations, its relevance as a security institution will be significantly diminished.

Rob de WijkDirector of the Hague Center for Strategic Studies

The current Ukrainian crisis should serve as a wake-up call for Europe. Russia’s occupation of Crimea is the price the EU pays for the neglect of its armed forces, a financial crisis that spiraled out of control, a lack of strategic thinking, and political disunity.

Since the end of the Cold War, Europe has imposed on Russia German unification, NATO enlargement, and Partnership for Peace agreements, a series of accords between NATO and former Soviet states. In 1999, NATO fought the Kosovo war against Russia’s ally Serbia. Ten years later, Poland and Sweden initiated the EU’s Eastern Partnership with post-Soviet states of “strategic importance.” Geopolitical objectives (read the weakening and isolation of Russia) have played an important role in most EU foreign policy decisions.

Humiliation after the collapse of the Soviet Union, together with the weakening of the West, explains the current behavior of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Postmodern Europe thought that geopolitics would be something of the past. Even U.S. President Barack Obama said that Putin’s actions in Ukraine put him on the wrong side of history. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry accused Russia of “nineteenth-century” behavior.

They were wrong. Power politics are still very much alive.

Andrew DuffMember of the European Parliament and constitutional affairs spokesman for the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe

Europe does not need Vladimir Putin to wake it up, but the EU does need to learn how to steer a clearer strategic direction in Eastern Europe and Turkey.

The Ukrainian crisis was foreseeable once the country’s successive post-Soviet presidents and ruling elites failed to take a serious grip on the drive to constitutional liberal democracy or to combat corruption. The last straw was when the Ukrainian parliament voted on February 23 to repeal a law on regional languages (including Russian), making Ukrainian the sole state language. It was no wonder that Putin, high on the success of the Sochi Winter Olympic Games, was enraged enough to make a grab for Crimea.

Let’s hope the Russian grab ends there. The good news is that Moscow cannot afford a long military campaign. When Putin’s generals ask him for more money, he will have to say no. And Russia’s powerful oligarchs are seduced not by nationalistic gestures but by the continued opportunity to get rich quick. Financial instability is Putin’s greatest enemy.

What should the West do? With Russia, it should focus on smart words, sanctions, boycotts, and asset recovery, coupled with intensive diplomacy. With Ukraine, it needs to offer political and economic support. Regardless of Europe’s moral case, the EU has interests too. It needs to find the gumption to articulate and promote them.

Fabrizio GoriaFinancial reporter at Linkiesta

Vladimir Putin’s threats are a chance for the EU to take the quantum leap that Ukraine deserves and say what it stands for in Europe’s East.

The echoes of the Cold War seem to be back. Ukraine’s political, diplomatic, and financial crisis could become a serious threat to the EU’s fragile stability and precarious credibility. Since Ukraine’s former president Viktor Yanukovych rejected an association and free-trade agreement with the EU in November 2013, the bloc does not have a clear position on Ukraine.

In short, Ukraine is a failure for the EU and its European Neighborhood Policy. A new state has de facto appeared on the map, but no one dares to talk about it explicitly. And it is hard to believe that the EU can act decisively enough now to stop the spillover of Yanukovych’s removal.

A diplomatic crisis is not what the EU needs—not on the eve of European Parliament elections, at least. Populism is on the rise in the EU’s periphery. To contain Euroskeptic political parties, the EU must show that it can live up to people’s expectations and dreams.

The EU urgently needs to clarify its stance in Eastern Europe. It is clear that the EU has not done enough to avoid losing Ukraine. Perhaps it would feel encouraged to do more to win it back.

Roderick ParkesHead of the EU Program at the Polish Institute of International Affairs

Russia has certainly given the EU a jolt, but I’m not sure it’s woken it up. Rather, Europe risks becoming Vladimir Putin’s creature. With armchair warriors wheeling themselves out of retirement, it’s not just that the EU seems to have undergone a collective brain transplant. Europeans are also dancing to the Kremlin’s tune, unwittingly confirming Moscow’s assumptions about the West.

Sometimes this can be flattering, for example Putin’s notion that the EU’s weak and bureaucratic European Neighborhood Policy is in fact an aggressive geopolitical masterstroke. More often, however, it highlights how poorly Brussels understands Ukraine: the EU’s emphasis on releasing the discredited former prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko confirmed Russian cynicism about “normative Europe.”

In a decade, Europeans will look back and wonder how Putin led them to forfeit their soft power, how he hemmed them into an unstable neighborhood that he no longer wants, and how he turned them into an international player without a team.

In fact, it will be the EU’s lack of nous that delivered all this. There are some excellent strategists in the EU who have a clear idea of where Europe needs to be, and what the right combination of muscle and mouth is. It would be better if they were the ones to wake Europe up.

Gianni RiottaMember of the Council on Foreign Relations

Europe is already awake. The trouble is, it does not know what to do.

Seven decades of peace have slowed the EU’s response to international crises. The UK can dispatch a fleet to the Falklands, France can send troops to Mali or Libya, and Portugal can fight a late colonial war in Mozambique and Angola. But when war hit hard in the Western Balkans, Europe did nothing until the United States decided to stop Serbian dictator Slobodan Milošević.

France and the UK are the only EU member states that used to have decent defense budgets, but now even their resources are being butchered by the EU’s debt crisis. Today, Paris and London pretend to follow a hard line against Vladimir Putin, while Berlin pretends to negotiate. Meanwhile, Italy is puzzled, torn between its muscular new young premier, Matteo Renzi, and old Russian oil interests.

The EU was born in the cozy safety of the Cold War, protected by U.S. muscle. The union was enlarged in the naive years after the fall of Communism, when well-intentioned economists flocked to Moscow, trying to teach Russians what to do with their derelict rubles and kopecks. Then Putin came along, and the atmosphere returned to the bloody days of 1918–1919, when Kiev was torn between Russians, Ukrainians, Bolsheviks, Germans, nationalists, and Cossacks.

Today, as yesterday, the real question is not what Europe wants to do vis-à-vis Putin or Crimea, but what Europeans want to do with themselves.

Julianne SmithSenior fellow and director of the Strategy and Statecraft Program at the Center for a New American Security

Vladimir Putin may well wake up Europe—but not nearly to the extent that many would like.

If you are hoping that Russia’s military aggression in Crimea will alter the downward spiral of European defense budgets, you’re likely to be disappointed. Most EU finance ministers will continue to view defense as a convenient place to find cost savings, especially in the face of the NATO drawdown in Afghanistan this year.

If you are looking for the crisis in Ukraine to produce greater unity and momentum from the EU’s foreign policy arm, again, you might be left empty-handed. The EU’s statement following its emergency foreign ministers’ meeting on March 3 offered few signs that it’s contemplating anything that substantive. What is more, divisions across Europe over the degree to which the West should pursue confrontational policies such as sanctions are a reminder of just how challenging it is for the EU to speak with one voice.

If, however, you would like to see the EU do more to focus on the safety and prosperity of its immediate neighborhood—perhaps in the form of a collection of like-minded allies—there are reasons to be encouraged. In recent weeks, a handful of EU member states, especially Poland, have shown remarkable leadership in addressing Russian aggression, assisting the new Ukrainian government, and reassuring neighboring countries.

Damon WilsonExecutive vice president of the Atlantic Council

Over recent years, European defense policies have resulted in an ever weaker political commitment to the transatlantic alliance. Vladimir Putin may stop this downward spiral—but not overnight. Just as Europe was slow to appreciate the gathering storms in the 1930s, many Europeans have so far concluded that Putin’s increasing authoritarianism at home and aggression against his neighbors would not affect them.

They were wrong. Putin has succeeded in reconstituting his ability to project Russian power into the heart of Europe. More seaworthy Russian ships now patrol the Arctic and Baltic Seas, where they were once absent. More capable Russian forces are now concentrated on NATO’s Baltic border. More accurate Russian missiles now target Poland and Romania. More lethal fighter aircraft routinely violate Swedish and Finnish airspace. And Russia more often exercises land invasions of Europe.

Under Putin, Russia has been hard at work to reverse the outcome of the Cold War. He has played a zero-sum game even as the West has insisted it is not. Russian forces now occupy territory in Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova. Coercion has produced feigned fealty in Belarus, Armenia, and part of Central Asia.

Europe is waking up. But many are attempted to hit the snooze button just one more time. They should resist—for the sake of those in Baltic and Europe’s East.