Cornelius AdebahrNonresident Fellow at Carnegie Europe

Hardly. That’s because too many among Europe’s leaders—at EU or national level—appear to think that U.S. President-elect Joe Biden means a return to some good ol’ days.

Yet, the world has changed since whenever that was, and so have the United States. Enough has been written in the past days about how much a President Biden will focus on “building back better,” but at home. It’s time for Europeans to grasp what that means.

Because if the chances of a “transatlantic reset” depend on who the next U.S. president is, its actual revival hinges squarely on what the Europeans are willing to do. To put it in very simple terms, Biden will only have to signal that he wants the allies to be partners again, but the latter will have to deliver. That means strengthening the European project through further integration—in particular in eurozone matters to prevent another financial crisis—and taking care of the many crises in the EU’s neighborhood.

The great leap forward for European policymakers and strategists would be to acknowledge that Europe’s “autonomy” is actually in the transatlantic interests—without it, there is no real partnership with Washington, only extended dependency. At the global level, rather than just confronting China in what is perceived as systemic rivalry, this means jointly tackling the issues of public health, climate action, and digitization in order to prove the effectiveness of the democratic, multilateral model.

In short, no pleasure cruise but a rough ride.

Krzysztof BledowskiSenior Council Director and Economist at the Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation

It’s hard to say, since U.S. President Donald Trump had provided convenient cover for Europe to duck cooperation on several fronts.

Some carryovers of transatlantic import from the Trump era are here to stay. Europe could chip in a few of those.

- China: Europe will delight the United States if it opens talks on common rules in future technologies—including AI and digital flows—with Western allies to preempt China from imposing its own.

- Trade: It is in Europe’s and the United States’ interest to keep trade disputes adjudicated internationally. Brussels should signal that it is ready to work with Washington to resolve the World Trade Organization (WTO) appellate court gridlock.

- Democracy: Europe might find a receptive ear in Biden’s corner on human rights and EU cohesion. Washington holds important cards in bilateral relations with Poland and Hungary. Brussels would be delighted if Washington found ways to leverage this influence to bring more internal cohesion to the EU.

- Global peace: Times have changed and U.S. taxpayers have little appetite for America to serve as the world’s gendarme. If the United States pivots to Asia, Washington will expect Europe to mind its neighborhood. This means Europe should build up military strength and push back hard alongside the United States against Russia’s efforts to weaken European stability.

Piotr BurasHead of the Warsaw Office of the European Council on Foreign Relations

Not yet. At least not collectively. An adequate response to Biden’s presidency would have to focus on the idea of European sovereignty. America needs a Europe which is able and willing to act on its own, even if its interests may sometimes clash with those of the United States.

However, the idea of European sovereignty may unite Europeans in political declarations, but it still divides them in real life. France would love to lead Europe toward “autonomy” (also from the United States), but it lacks followers because of its leadership style and only half-hearted Atlanticism.

Germany’s approach would be more appealing, but Berlin lacks the resolve to lead. And many in Central and Eastern Europe still want to believe that the unpredictability of U.S. policy is an unfounded theory of America’s enemies.

Europeans’ difficulty to come to terms with the challenge (and opportunity) that Biden’s presidency will pose, has to do with the uncertainty about what the new U.S. president will ask of them—for example on China and on trade—as well as about the character of his term.

Will Europeans and Americans be able to forge a new, stable transatlantic partnership which will endure for years or even decades? Or will it become just a transition period followed by yet another “Trump”? We should definitely hope for the first and prepare for the latter.

Allison CarragherVisiting Scholar at Carnegie Europe

Some are and some aren’t.

While many European leaders are optimistic a Biden presidency will be pro-EU, pro-NATO, and usher in a new era of transatlantic cooperation, others are skeptical or have outright refused to acknowledge Biden as president-elect.

Contrary to an election-day tweet from Donald Trump Jr. painting all of Europe with a uniform “red wave” (except for Croatia, which was pictured as ocean), Europe’s leaders are hardly united in political opinion. They are fragmented by their own divisions—a lot of which resemble issues raised during the 2020 U.S. presidential election.

Leaders in Hungary and Poland have leveraged populism to hollow out democratic institutions. Alleged pushbacks of migrants are reminiscent of racially fueled police brutality. “Anti-maskers” have marched down German, Czech, and Spanish streets. And the EU’s ambition of “strategic autonomy” seeks to “Make Europe Great Again.”

In short, both sides of the Atlantic are grappling with similar forces.

But what about those European leaders committed to confronting these challenges at home and working constructively with an America they recognize as equally divided? Those leaders are ready for a Biden presidency.

Robert CooperUK Council Member at the European Council on Foreign Relations

They ought to be ready: they’ve waited four years. So let’s make it work: a partnership on climate action, Iran, and China; a big joint push in the Balkans; effective collaboration on European defense; and an EU-UK agreement that can be built on.

The special subject is democratic renewal. The United States needs it; so does the EU, for example to deal with Hungary and Poland. One day, even the UK might get around to it.

Caroline de GruyterEuropean Affairs Correspondent for NRC Handelsblad

Yes, they are, but for the wrong reasons. In November 2016, nobody was ready for a Trump presidency, despite the warning of the UK Brexit referendum a few months earlier. It took a bit of time to conceptualize how Europe should react.

But it happened: Europe needed strategic autonomy, a Rorschach test on which everyone projects their own obsessions.

The idea was not so much to fill the vacuum left by a debilitated superpower as to figure out how to protect our values-based model in a world where we would be left to fend for ourselves. The concept has a lot of potential, but not much has (yet?) come out of it.

Perhaps unconsciously, we hope for a return to the status quo ante. Still, the leaders of Europe have to realize that it is precisely the strategic autonomy of the European Union that would make it an attractive and useful partner for the United States.

At some point around the end of January 2021, Washington will move away from seeing the transatlantic partnership as a zero-sum game. Europe and the United States are both stronger together, they both benefit from each other’s strength. There is some work to do before we can be fully ready.

Mathieu DuchâtelDirector of the Asia Program at Institut Montaigne

Most in Europe crave for a Biden presidency that would seek prior transatlantic coordination on major international issues in a reliable and predictable way. China policy will be an excellent barometer of the quality of the transatlantic partnership, one that could quickly provide accurate initial measurements.

Under the Trump administration, Europe and the United States have converged like never before: on their assessment of the domestic governance trends and the international behavior of China under President Xi Jinping; on the urgency to find efficient solutions to trade imbalances, intangible technology transfers, and asymmetries in investment practices; and on the importance to take seriously China’s choice to rival Western democracies on governance models and the need to offer alternatives to Chinese economic development packages, especially in the Indo-Pacific space.

The foundations for joint transatlantic action on China policy are thus relatively strong.

A Biden administration with a focus on carbon emissions, health security, human rights, and multilateral governance will need to find the right balance between those four priorities and his realistic agenda of strategic competition with China, for which Europe is currently in an unusual spirit of cooperation.

Michel DuclosSpecial Advisor for Geopolitics at Institut Montaigne

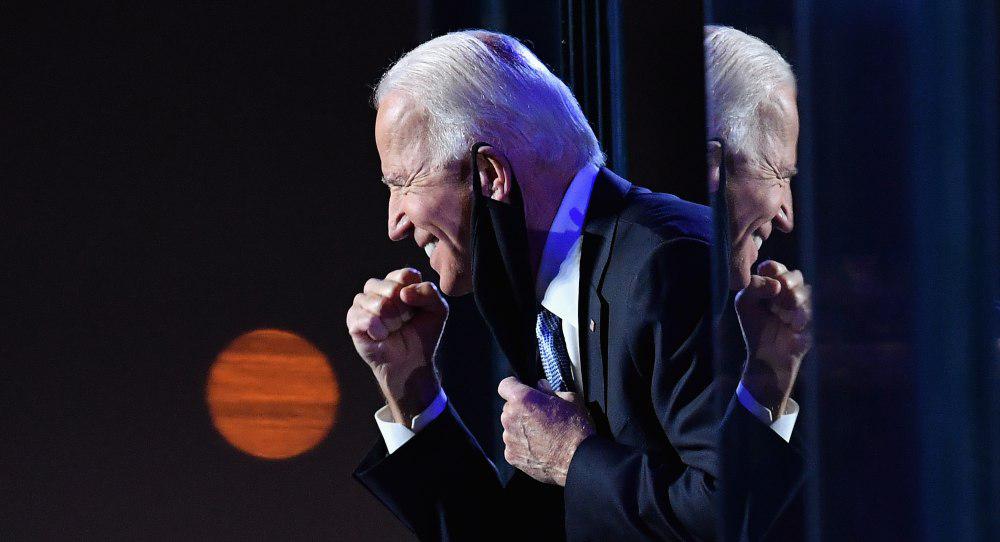

In light of the historic opportunity provided by Joe Biden’s election, European leaders are certainly aware that they need to “do more” to secure the attention and commitment of the Americans.

The question is, will they be able to agree on what “doing more” actually entails?

For some, the answer is to increase burden sharing in terms of defense spending, reaffirming their allegiance to NATO. For others, the French included, it is now necessary to redefine a transatlantic agenda that goes beyond defense. Such an agenda must include China policy, climate change, tech governance, WTO reform, and other geoeconomic issues.

This is where Europeans and the EU can prove to be capable and useful partners to the United States, even though it may mean agreeing to disagree on certain aspects, such as the taxation of major companies or GAFA—Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon.

In order to achieve a European consensus on this agenda, German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s personal commitment will count a great deal, as will the strength of the Franco-German tandem and the determination of the European Commission. What should also be kept in mind is that the Washington mindset is historically NATO-centered, and that post-Brexit Britain may complicate matters.

Peter KellnerVisiting Scholar at Carnegie Europe

Joe Biden’s election presents Europe with a big problem—and a big opportunity.

The problem is that the future political leadership of the continent is uncertain. Here’s a thought experiment. Suppose Biden could call just one European leader to discuss the next four years. Who should he call?

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, when the UK has left the EU and is no longer useful as an intermediary between Washington and Brussels, Berlin, and Paris? Angela Merkel, who steps down as German chancellor in the second half of 2021? Emmanuel Macron, who might not be reelected as France’s president in spring 2022? If “being ready” requires decisive political leadership that is likely to last, then, no, Europe is not ready.

However, Europe has one huge, specific opportunity. One of the great EU successes of recent years has been its commitment to fighting climate change. Biden says he will take the United States back into the Paris Agreement. This will be just the first step in accelerating international efforts to save the planet.

Europe has led the way in developing policies and technologies to meet the challenge. It now has the chance to lead the world—including the United States—in designing standards and setting targets for the next twenty–thirty years.

Rem KortewegSenior Research Fellow at the Clingendael Institute

Expectations are high and the wish list is long. Under Biden, European leaders are anticipating a new transatlantic dawn. Some of those expectations will be met; Biden the internationalist will embrace multilateral institutions and look to the EU and its member states as partners and allies, not as free-riders or foes.

But it’s unclear whether Europe’s leaders are prepared for U.S. demands or the inevitable challenges that may arise.

Throughout the Trump presidency, Europeans could complain about tweets and tariffs, while theorizing about strategic autonomy. This time round, Europe will have no excuse. It has what it wants: a U.S. president that will reach out across the Atlantic. And now it must deliver.

It must do so by taking on a greater role for security in its own neighborhood—Europe is irrelevant in Syria and Nagorny Karabakh and ineffective in Belarus, the Eastern Mediterranean, and Libya—or by working with the United States to push back against China’s growing security, tech, and trade clout.

European foreign policy coherence will be tested more in the Biden era than it has been in the Trump era. And Europe should also be prepared for disappointments. Though many trade tensions with Washington may dissolve, European taxation of American tech firms could spark new ones. Biden is good news, but the time for transatlantic dreaming is over.

Péter KrekóExecutive Director of Political Capital

The Biden presidency provides a huge opportunity for the United States to rebuild its transatlantic ties and improve its tarnished image in Europe. It’s going to be difficult. There is an overwhelming welcoming attitude toward the incoming U.S. administration—at least in Western Europe—as it will see Europe and the EU as an ally, not as a burden.

At the same time, there are widespread fears that defeating Trump will fuel Trumpism further and that the American populist right can come back even stronger in 2024 after four desperate years of (post-)coronavirus-pandemic recession and slow recovery.

But the United States is still a model, and this change is crucial. The fact that tribal politics can be defeated from a traditional centrist ticket can be an important reassurance for many democratic forces in Europe. And the fact that the “tribal zeitgeist” does not last forever is important feedback for opposition authoritarian populists in Western Europe and for governments in Central and Eastern Europe.

The new U.S. administration should keep focus on malign, foreign, sharp-power influence in Eastern Europe but also pay more attention to democratic backsliding—in the region, the two go hand in hand.

Stefan LehneVisiting Scholar at Carnegie Europe

Hardly. Some pundits thought that four more years of Trump would be just what the EU needed to finally achieve unity. But in fact, during the Trump years, divisions in Europe deepened and coherence declined.

Unfortunately, the U.S. president had like-minded partners in the EU who shared his nation-first mentality and his authoritarian instincts.

Biden’s victory is good news because it weakens right-wing populism and because EU unity cannot be strengthened without constructive transatlantic relations.

But now, European leaders risk relapsing into the lazy posture of overly relying on U.S. leadership. And this leadership will probably not be forthcoming. A deeply polarized American society, a divided government, and mounting domestic problems will absorb most of the attention and energy of the incoming Biden administration.

What is left will primarily be devoted to managing the rivalry with China. It’s great to have someone in the Oval Office who doesn’t consider the EU an enemy. But the old “hegemonic partnership” will not return.

In fact, a Biden administration focused on the Indo-Pacific might accelerate the decline of Europe’s weight on the global scales. If Europeans wish to continue to have a meaningful role in managing regional and global challenges, they cannot rely on anyone but themselves. It is therefore high time to stop talking about strategic autonomy and instead start implementing it.

Denis MacShaneFormer UK Minister for Europe and Senior Advisor at Avisa Partners

No. They were not ready for a Trump presidency which rubbished the EU and attacked NATO, not ready for a Barack Obama presidency which pivoted to Asia and began regime-change interventions in Libya and Syria but then gave up, and not ready for a George W. Bush presidency and its disastrous 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Americans look at the wealth of Europe, at the 1.4 million under arms across EU member states which are never used to promote the EU’s proclaimed foreign policy goals in the Western Balkans or Eastern Mediterranean, and at the strident insistence that foreign policy is the reserve of national governments, not Brussels officials.

In 2020, Biden has called Xi a thug and said he would work with the Turkish opposition against President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and stop U.S. arms sales to Turkey to put pressure on its military to stop Ankara’s military adventurism.

Is anyone in the EU ready to challenge China or even Turkey? Europe will welcome a Biden return to U.S. multilateralism. But EU nations will not sink their differences and create an effective European multilateral foreign policy to stand by for Team Biden. Indeed, the latter may feel let down by the EU’s minimalist, lowest-common-denominator approach to geopolitics.

Claudia MajorHead of the International Security Division at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Counterintuitively, a Biden presidency might be divisive for Europeans. They have to reconcile domestic, European, and transatlantic expectations—otherwise, they risk quickly messing up the hoped-for transatlantic honeymoon.

There is indeed no single European reaction to Biden, but many. Central and Eastern Europeans, but also the UK, fear to get less U.S. attention for their worries and wishes. They dread to see their special bilateral relationship suffer. And they have to accommodate their European partners again.

Others, like France, fear that the current enthusiasm naively overlooks the shifting U.S. priorities and the changing world order and that it breaks the momentum for much-needed European sovereignty.

And then there is Germany, likely to be the new transatlantic go-to partner for a Biden administration, which might create some jealousies in other capitals. Berlin might be called upon to manage U.S. expectations and reconcile the various European positions into one European voice.

And U.S. expectations are high for both Germany and Europe. They involve fulfilling old promises like burden sharing in defense spending and newer challenges like dealing with China. There are no longer any good excuses not to fulfil some of those U.S. expectations now that the wished-for president-elect Biden is asking for support—and not the bully Trump.

But fulfilling U.S. expectations might clash with domestic demands, for example if greater defense commitments to boost transatlanticism are disadvantageous in domestic elections. This clash could materialize quickly with the German and French elections in 2021 and 2022, respectively.

Mary C. MurphyLecturer at the University College Cork

The sense of relief among European leaders following the election of Joe Biden as the next president of the United States is palpable. However, the significance of the president-elect’s victory is best read as signaling—initially at least—a steep change in the style more than the substance of EU-U.S. relations.

Trump’s inconsistent and often incoherent approach to foreign policy confounded and frustrated many U.S. allies. European leaders will be decidedly more comfortable dealing with a Biden administration, which will lean toward traditional norms, rules, and expectations associated with international relations.

A relationship based on mutual respect, however, does not remove the challenges facing the transatlantic relationship. On issues of trade, digital tax, and defense, differences will remain, and tensions will persist. European leaders should not underestimate the policy and political challenges ahead. There are no easy and ready fixes.

Biden’s administration may also be hampered by a Republican-dominated Senate which is less favorable to closer EU-U.S. relations and less committed to rebuilding damaged relations.

However, although Joe Biden may not be able to immediately resolve all of the challenges facing the transatlantic relationship, his stated desire to restore good relations bodes well for a more constructive and cordial era in relations.

Marc PieriniVisiting Scholar at Carnegie Europe

Biden’s election undoubtedly triggered a huge sense of relief across the European Union, as most European leaders know him well and respect him. The Irish and the French have an even softer spot because of Biden’s ancestry.

Also, part of the relief is that Donald Trump will be gone. He was the first-ever U.S. president to be openly hostile to the EU since its inception, he regularly threatened German cars and French champagne with high tariffs, and he supported Brexit.

Despite lingering issues in the trade field, the aerospace industry, or about the taxation of GAFA, Europeans will hope for four ingredients in Biden’s foreign policy: a civilized dialogue with European leaders, a reaffirmation of the shared commitment to NATO, a commitment to fight climate change, and a behavior consistent with the values shared across the Atlantic.

Yet, a Biden administration will still want to see Europeans spend more on defense and will probably keep disengaging as the security guarantor in the Middle East, while focusing on relations with China.

This implies that European leaders will have to take their destiny into their own hands, irrespective of who is U.S. president. Many have said it publicly since May 2017. Will they do it?

Daniela SchwarzerDirector of the German Council on Foreign Relations

Most European leaders want to seize the chance to rebuild the transatlantic alliance and work alongside the United States in multilateral organizations. But they are not prepared for three things:

First, transition chaos. Trump supporters may use his myth about Biden cheating and Trump being “stabbed in the back” to justify violence against fellow citizens. The outgoing president may cause an international crisis by incalculable provocations during his remaining weeks in office.

Second, once he has moved into the White House, Biden will govern a deeply divided country. His approach to external affairs will be far more civilized, respectful, and rules based. But his demands will be strong: Europe and in particular Germany will have to bring more to the table in terms of money, troops, and a hard line on China.

Third, the EU is not prepared for its own internal divisions. As the UK has left the EU and the U.S. government may have little patience for Brussels processes, Berlin may turn into the prime European go-to place for Washington. Neither Paris nor Poland will appreciate that—for different reasons.

Involuntarily, the United States may act as a divisive power, even with Joe Biden at the helm. Berlin’s goal to hold the EU together may become even harder to achieve.

Paul TaylorContributing Editor at Politico Europe and Senior Fellow at Friends of Europe

EU leaders are ready to harvest the low-hanging fruit of a Biden presidency by rebuilding cooperation with the United States to fight climate change and the coronavirus pandemic, rein in Iran’s nuclear program, and reform multilateral institutions like the WTO, the World Health Organization, and perhaps NATO.

But there is no consensus on how much more Europe should do for its own defense or as a security provider in its Eastern and Southern neighborhood. German Defense Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer’s comment that “illusions of European strategic autonomy must come to an end” reflected the temptation to cling to the comfort blanket of American protection and avoid hard questions about when and how Europeans should use military power on their own.

EU leaders don’t yet have a coherent stance on responding to China’s assertiveness—the top foreign policy issue in Biden’s in tray—despite limited progress on toughening trade and investment defense instruments and shielding critical infrastructure. Nor do they have a common position on dealing with Russia’s muscle flexing and Turkey’s aggressive behavior or on taxing and regulating dominant American digital platforms.

To be ready for Biden, Europe needs to be better prepared to defend its own interests and act as a self-reliant partner with Washington.

Nathalie TocciDirector of the Istituto Affari Internazionali and Special Advisor to EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell

The 2020 U.S. presidential election has been, no more, no less, about democracy in the United States. This is true for its citizens, but it is also true for liberal democracies, including in Europe.

Joe Biden’s victory represents a defeat for European nationalist populists, who saw in Trump a leader and role model. Furthermore, Biden will seek genuine partnership across the Atlantic. His administration will work alongside—and not at cross purposes with—the EU in the Balkans, it will coordinate with Europeans over Ukraine, Belarus, the Caucasus, Russia, and Turkey, and it will welcome European facilitation to ease its way back into the Iran nuclear deal.

From coronavirus response to climate, nonproliferation, and economic recovery, with Biden, Europeans will have a U.S. partner again in global governance.

However, with a President Biden, some Europeans will be tempted to stick their heads in the sand, putting global ambitions to rest. Others will argue that pursuing European strategic autonomy is incompatible with a strengthened transatlantic bond, and that with Joe Biden in the White House the priority should be the latter—certainly not the former.

European autonomy is not incompatible with a stronger transatlantic bond but is rather the precondition for it. Only a more capable and thus more autonomous Europe can meaningfully work with Biden’s United States to make multilateralism great again.

Özgür ÜnlühisarcıklıDirector of the Ankara Office of the German Marshall Fund of the United States

The Turkish government is not ready for the Biden presidency by any means. Erdoğan had a strongly positive relationship with Trump, who has protected Turkey from the anti-Turkey, anti-Erdoğan sentiment of the U.S. Congress and the wider policy community in the United States.

Biden and Erdoğan have publicly manifested their mutual dislike, and Biden is unlikely to use his political capital for Erdoğan. Literally the only foreign policy goal the Biden team has communicated is cohesion within the transatlantic alliance, which means that Biden will not approach Turkey’s relations with Russia with understanding and therefore not avoid imposing the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act against Ankara as Trump did .

Moreover, Biden is likely to be vocal about the democratic backsliding in Turkey, which will lead to counterattacks from Erdoğan.

Biden may bring on board Obama administration officials, including those who played a key role in developing the cooperation between the United States and the Syria-based Democratic Union Party (PYD). Turkey considers PYD an offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and a terrorist movement.

If the new U.S. administration decides to strengthen cooperation with the PYD, this by itself could be sufficient to trigger a crisis.

Having said all of this, mutual American and Turkish interests could still lead Biden and Erdoğan to seek ways to bridge their differences. Erdoğan has proven to be pragmatic in the past and may as well adapt to this new era.

Pierre VimontSenior Fellow at Carnegie Europe

No miracle here. The mere notion of the twenty-seven national EU leaders getting their act together and proposing an ambitious working agenda to the new U.S. president was never going to be a foregone conclusion.

No one could seriously expect from the EU a sudden capacity to unite, as the long, simmering feud between the promoters of a strategically autonomous Europe and the defenders of a more traditional, transatlantic line has not really abated. From that point of view, the recent statement by the German defense minister on EU defense prospects in the aftermath of the U.S. election was a sobering reminder.

Yet the final outcome of the U.S. election, showing a highly polarized country, is probably going to put Europeans in an even more difficult place than expected. In this “in-between zone” where Democrats and Republicans are forced to work together and heal the many tensions corroding the American nation, domestic politics will be the incoming U.S. administration’s main priority.

With a far less bombastic style than during the Trump era, internal considerations are to shape U.S. foreign policy and put strong pressure on Europeans. For the EU, protecting its own interests more than ever while sticking to its transatlantic creed will remain a most difficult balancing act.

This blog is part of the Transatlantic Relations in Review series. Carnegie Europe is grateful to the U.S. Mission to the EU for its support.