In April 2020, an internal report circulated by the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, a government-affiliated think tank associated with China’s top intelligence agency, contained a grave warning for China’s leadership. According to reporting by Reuters, it concluded that “global anti-China sentiment is at its highest since the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown.”

Many countries are realizing that China’s rise and ensuing departure from tenets of domestic and foreign policy, instilled during the era of former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, break from their own views. Policymakers are increasingly alarmed, devising new means to protect their own systems of government, economic prosperity, and national security from a more assertive China.

Officials in the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump have been the most vocal, lambasting Beijing for a growing list of concerns but failing to put forward an effective response. Beijing’s ongoing domestic crackdown—evidenced by the internment of at least a million Uighurs in China’s Xinjiang Province and ongoing protests in Hong Kong—and discriminatory trade and economic policies, coercive foreign policy practices, “Wolf Warrior”–inspired diplomacy abroad, and military expansion in its direct periphery have heightened this global pushback and scrutiny.

China’s leadership may not recognize its own role in sparking such global pushback. Influential Chinese scholars have questioned the unfavorable international environment and argued that Chinese actions in the wake of the coronavirus should have garnered China acclaim rather than criticism. Washington, though outspoken in criticizing Beijing, needs to galvanize collective action with partners and allies to effectively address the growing number of shared concerns about China’s behavior.

Where Is China Facing Pushback?

In recent years, China has expanded its diplomatic and economic relationships, launching new institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and positioning itself as a donor of much-needed public goods through policies like the vast amounts of infrastructure investment through the Belt and Road Initiative. As China’s influence has grown, so have the number of countries concerned with its lack of economic reciprocity, dominant technological policies, coercive foreign policy practices, and regional military ambitions.

This dynamic is most apparent in the rapid deterioration of the U.S.-China relationship. Just this month, the White House released a report arguing that growing Chinese power “harms vital American interests and undermines the sovereignty and dignity of countries and individuals around the world.” While perhaps the most obvious case, Washington is not the only example of hardening views against Beijing.

The EU, for example, has labeled China a “systemic rival” and “economic competitor,” reflecting hardening attitudes toward Beijing across Europe. Chinese practices of limited market access for foreign firms, industrial policies that explicitly displace international competitors, and preferential treatment for state-owned enterprises have pushed European countries like Germany and France to proactively prioritize their own development.

European concerns extend beyond economic reciprocity. Recognizing the national security vulnerabilities presented by using Chinese 5G technology, some European countries are reassessing Huawei as a provider of 5G infrastructure. In January 2020, the EU unveiled a recommended strategy for its member states aimed at preventing Beijing from dominating 5G markets and exploiting security vulnerabilities. Due to security concerns, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Poland, and Romania have all signed agreements with the United States on 5G security that would limit the role of Huawei in their markets. Even the UK, which decided in January to allow Huawei a partial role in building out its 5G infrastructure, recently reversed course and is likely to pass legislation requiring Huawei to have no role in the country’s 5G networks by 2023. Instead, Britain has proposed forming a so-called “D10 club of democratic partners,” which would include the G7 countries—Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, and the United States—plus Australia, India, and South Korea. The collective goal would be “to create alternative suppliers of 5G equipment and other technologies to avoid relying on China.”

In Australia, the first country to ban the 5G technology of Huawei and fellow Chinese firm ZTE, China faces growing scrutiny after Canberra uncovered worrisome Chinese meddling in its domestic politics. In response, Australia enacted stringent regulations stopping Beijing from undermining its political system, such as former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull’s overhaul of espionage and intelligence laws in December 2017 preventing Beijing from buying political influence and promoting Chinese interests.

In Asia, where strong economic ties with China are critical to development, Beijing has still managed to drum up resentment for its unyielding position on territorial claims in the South China Sea. Last year, Vietnam issued its first defense white paper in ten years in which it rejected Beijing’s claims and criticized China’s maritime tactics, citing “unilateral actions, power-based coercion, violation of international law, militarization, change in the status quo, and infringement upon Vietnam’s sovereignty, sovereign rights, and jurisdiction as provided in international law.” Other claimants, including Malaysia and the Philippines, are building up their militaries and strengthening outposts that would help push back against Chinese expansion.

Perhaps the most worrying signs for China’s leaders are the growing international concerns surrounding issues of Chinese sovereignty, which Beijing often calls a core interest. Last year, twenty-two countries issued a statement to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights decrying China’s detention of at least one million Muslims in Xinjiang. The number of signatories represented was near double that of a similar statement issued in 2016. As China prepares to enact a national security law in Hong Kong that would further undermine its commitment to the one China, two systems policy, nearly 200 policymakers worldwide and multiple countries have issued statements condemning Beijing’s move. Some countries have even begun calling for change regarding Taiwan, a subject on which silence has been a critical requirement for relations with Beijing. Last month, thirteen UN member states submitted a proposal to restore Taiwan’s observer status at the World Health Assembly.

How Is China Responding to the Growing Pushback?

Criticism of Chinese policies, both at home and abroad, has revealed the grittier side of Beijing’s diplomacy. Frequently labeled “wolf warriors” after a highly popular patriotic blockbuster action film, Chinese diplomats have threatened economic retribution or taken to social media to chastise foreign governments that push back on Beijing. Chinese ambassadors in Denmark and Germany, for example, have warned of unspecified consequences if either country banned Huawei from their markets.

The coronavirus has only further highlighted this dynamic. While leaders in Washington and other capitals had clear political motivations to scapegoat Beijing for the outbreak to distract from their own policy failures, the pandemic has further accentuated Beijing’s more aggressive foreign policy. When more than 120 countries signed an agreement for an “impartial, independent, and comprehensive evaluation” of the “international health response to COVID-19,” Beijing saw this move as an attempt to expose its own role in the virus’s spread. In response, it took punitive actions against Australia—which initially called for the investigation. China’s ambassador warned that Australia was going down a “dangerous” path, and Beijing placed tariffs on Australian imports of barley and beef.

In the UK, some have called for a tougher line on China amid growing concerns over Beijing’s wolf warrior approach. The same holds true in Canada, where the specter of Chinese retribution has loomed large ever since Beijing arrested Canadian citizens Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor back in December 2018. Since the coronavirus pandemic began, a growing number of Canadian policymakers have been reorienting their political messaging to demand greater accountability from Beijing for its own early failures to contain the virus’s spread. Incidents in a host of countries including Australia, Brazil, Canada, Cyprus, France, India, Kazakhstan, New Zealand, Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka, and Venezuela have heightened anti-China rhetoric and led these nations to speak out.

Furthermore, Beijing has sought to censor its critics. Twice over the past two months, the EU has toned down rhetoric implicating China’s role in spreading the coronavirus following pressure from Beijing. In April, Brussels revised and softened language in a report that highlighted China’s “global disinformation campaign to deflect blame for the outbreak.” Just weeks later, the EU ambassador to China along with ambassadors from the EU’s twenty-seven member states allowed censorship of parts of an op-ed commemorating forty-five years of China-EU diplomatic relations that labeled China as the source of the coronavirus. EU officials and member states immediately raised concerns about what both these incidents might mean for future Chinese involvement in European politics.

What Is Driving This Approach and What Does It Mean for the United States?

Policymakers and analysts in Asia, Europe, and North America are raising serious and legitimate concerns about China’s growing influence. However, few voices in China acknowledge this. Several senior Chinese foreign policy advisers have urged Beijing to tone down its rhetoric. Chinese Ambassador to the United States Cui Tiankai also has distanced himself from the wolf warrior approach.

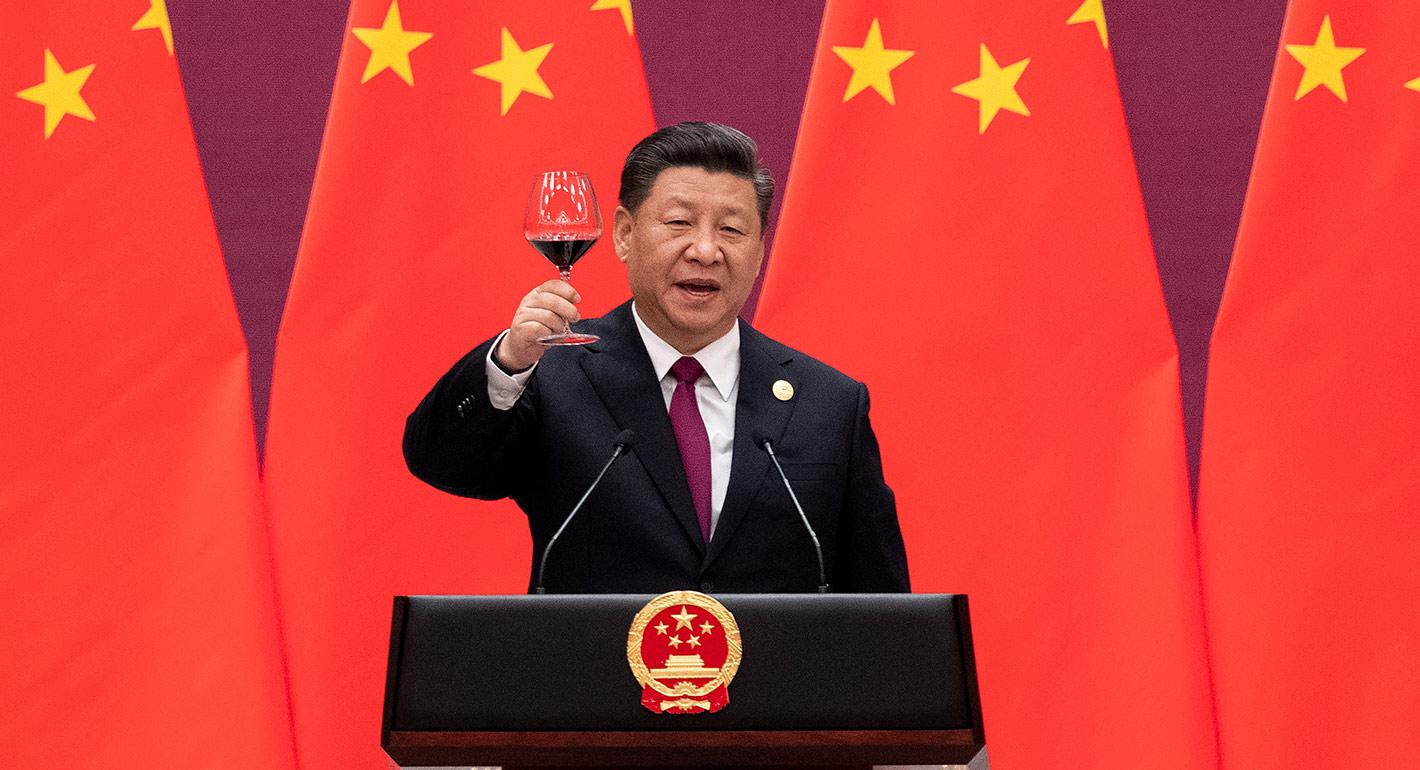

However, it appears that Beijing will not shift tactics anytime soon. Last fall, Chinese President Xi Jinping encouraged officials to “embrace a fighting spirit,” and last week, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi defended the approach and insisted it was necessary. Rather than adjusting its approach to account for greater global pushback, Beijing appears to be doubling down. Perhaps, despite facing a more hostile international environment, Chinese leaders recognize a unique opportunity to capitalize on discord between the United States and its allies and partners around the world.

Rather than raise the bar, Trump continues to lower it by mirroring Beijing’s worst policies, cutting off official dialogues at nearly all levels, and overreacting in ways that harm the United States’ own interests. Furthermore, the U.S. administration continues to forsake allies and partners, urging them to choose between Washington and Beijing without offering a clearly formulated plan. Trump has opened the door for Beijing to advance its strategic objectives without fearing a well-coordinated and comprehensive response from Washington and its partners in Europe and Asia.

The implications for U.S. policymakers are obvious. The United States should capitalize on growing concerns across a range of countries and align with like-minded partners to push back on China. As U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs David R. Stilwell remarked in late May, “The fact is that it’s not just U.S. and China . . . the world is finally recognizing that . . . Beijing is pushing a form of government that many only now are beginning to recognize as problematic.” While it is unreasonable for the United States to ask other countries to choose sides, growing global pushback presents an opportunity for Washington to better address Beijing’s most deleterious policies.

The authors are grateful for research assistance provided by Ethan Paul and Bernice Xu.