Source: Macro Polo

It’s often been said, including by my colleague Damien Ma in an excellent 2013 book, that China’s Communist Party has offered “prosperity without freedom” during the era of economic reform. To put this a bit differently, China’s people have been permitted by their Leninist rulers to grow rich and pursue material gains—so long as they accept the Party’s writ and forego organized challenges to its rule.

But if this does accurately describe China’s post-1978 grand bargain, then last month’s 19th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party makes clear that it no longer holds.

Hundreds of millions have grown prosperous during 39 years of economic reform. For these teeming millions, prosperity alone is, quite clearly, no longer sufficient. Their expectations now transcend wealth and economic mobility. Increasingly, they demand not just material gains but social ones too—equitable life chances, better welfare protections, safer food, drinkable water, cleaner air, and more responsive (if still unrepresentative and undemocratic) government.

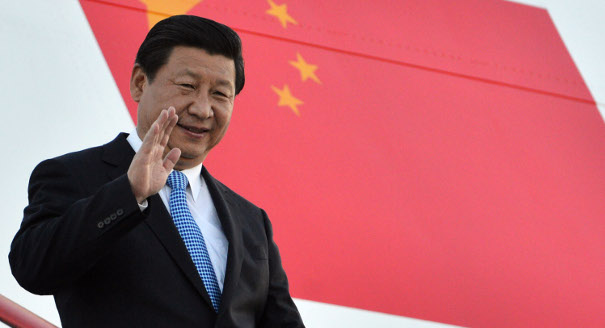

At the 19th Congress, Party leaders made clear that this message from the public has been sent and received. Xi Jinping, the Party’s general secretary and China’s president, devoted significant chunks of his more than three-hour speech to what he bluntly termed the public’s demands for “a better life.”

OLD THEMES, NEW URGENCY

Of course, a “better life” is hardly a new political theme in China. A decade ago, China’s last cohort of leaders—the tandem under President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao—began to talk earnestly about the need to enhance welfare protections and social equity. Now, this message has moved closer to the front and center of Party doctrine. And that can be seen from Xi’s speech and Party documents that have been released in the weeks since the Congress concluded. Indeed, whether or not the Party enhances social benefits will be a kind of scorecard for the next five years—a yardstick against which to measure whether, and to what extent, the Party is achieving its stated goals of social progress and improved governance.

But ironically, these themes are not, in fact, the ones that have dominated most portrayals of the Congress, especially outside China.

Instead, the “high” issues of Chinese politics—who’s up, who’s down, who’s in, and who’s out—not the “low” ones closer to the ground of Chinese people’s day-to-day lives have swamped all coverage for months. But it is these very localized questions that are increasingly central to the concerns of the leadership. And that is a striking contrast to the Congress’ powerful Leninist imagery, booming triumphal march music, and paeans to a confident, resurgent China.

The Congress’ underlying political message was unmistakable: “north, south, east, west, and at the center, the Party leads everything.” Party supremos aimed to project the image of a confident, unified, strengthening elite, pursuing the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” while assuring control and molding social and economic institutions in the Party’s preferred image.

But what exactly does it mean for the Party to “lead everything” when those who are being led—Chinese citizens—expect something different from what the Party has hitherto provided to them?

Party leaders appear to be asking themselves this question. And so it’s important to recognize how much fragility and uncertainty about the non-material aspects of governance and development lies behind the Leninist triumphalism.

Xi’s cohort seems to understand that China’s prevailing social and political contract has frayed.

THE “PRINCIPAL CONTRADICTION”

Surely, this is why Xi launched his second five-year term at the Congress by endorsing a major doctrinal change—one that implicitly recognizes the fraught circumstances of China’s economic reality and the growing expectations for change of an increasingly demanding citizenry.

Chinese Marxists have long stressed the need to think in terms of “contradictions”—the dialectical opposition of different forces or influences. Mao Zedong, the Party’s longtime chairman, made an intellectual career out of emphasizing the various “contradictions” and these formed the central thesis of one of his most famous essays, a 1937 piece titled “On Contradiction.”

When constructing their post-1978 reform edifice, Mao’s successors moved away from the chaos he had unleashed by defining their own so-called “principal contradiction” to guide the Party’s future work. The principal contradiction, they decreed, would be the gap between “the ever-growing material and cultural needs of the people and backward social production.”

In simplest terms, this meant that China’s new leaders sought to focus on modernizing the economy, lifting living standards and meeting material needs. This, they hoped, might also let pressure out of the political “balloon” that, in the aftermath of the chaos of the Cultural Revolution and the stasis of the mid-1970s, threatened further political fragmentation and perhaps could bring down the Party itself.

Enter Xi Jinping.

At the 19th Congress, Xi’s team changed the “principal contradiction.”

Instead of continuing to focus on the gap between people’s needs and backward economic production, the Party has now declared that it will focus on social needs and demands for welfare and equity. Indeed, Xi put this point rather bluntly in his speech: “What we now face,” Xi declared, “is the contradiction between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life.”

Put differently, Xi pitched a sort of “new deal” for China—one that moves beyond delivering prosperity to delivering improved governance and greater welfare gains. And while this is mostly rhetoric for now—with execution still to come—it is, in a sense, both an accurate assessment and formal recognition of the massive changes in Chinese society.

Bluntly put, the Party had dropped the ball in dealing with citizens’ new demands.

And that is probably why someone who is said to be “the chairman of everything” and “China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong” is now spending at least some of his time on matters as mundane as launching a “toilet revolution” aimed at “improving [the] people’s life quality.” Want to know what Xi Jinping is giving speeches about this week? Toilets.

CHINA’S THREE NEW CONTRACTS — SOCIAL, POLITICAL, ECONOMIC

But here’s the problem:

If one looks at how the Party is pursuing its efforts to address the new principal contradiction—if one looks, in other words, at where the Party actually appears to be taking China—then it’s clear that the story is not so straightforward as a simple effort to deliver “a better life” to the Chinese people.

Xi’s team means to meet heightened public expectations at the same time that it attempts to rearrange China’s three prevailing public “contracts”— elements of its social contract, political contract, and economic contract—all of which are fraying.

The “Social Contract”

The prevailing social contract is, in a sense, the “grand bargain” described above—an exchange between Party and public of economic opportunity for acceptance of constricted political space.

But the Party is moving away from this grand bargain not only because of pressure to deliver something more than merely material gains. It also faces threats from social dislocation, rising popular discontent, and slowing growth.

Many of the economic and structural reforms necessary to address these problems were shelved during Xi’s first term. So the Party’s challenge of meeting social, as opposed to just material, expectations has grown tougher because it now has to bridge a significant credibility gap with the Chinese public.

The “Political Contract”

China’s political contract, meanwhile, is also coming apart. The country’s post-1978 leaders, led by Deng Xiaoping, promised responsive, but not representative, government. The Party rejected demands for direct representation, much less democracy, by arguing that those things were unnecessary to meet public expectations and governance needs.

And yet much like the “social” contract, which has frayed in the face of rising expectations, this “political” contract has also frayed.

That is because China’s prevailing governance model is failing—badly—to deliver sufficient social services and other needs.

An unrepresentative government that China’s leaders claimed could nonetheless manage to be “responsive” just doesn’t look too responsive anymore, either.

This has happened, in part because Beijing has failed to replace the old system of welfare guarantees with a new one. In the past, China’s unrepresentative but ostensibly “responsive” state provided virtually all aspects of job security, social security, and retirement security, usually delegated through state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and other work units. That changed in the 1990s when SOEs were forced to dramatically curtail these functions and shed many of their welfare obligations.

The problems this introduced for millions of ordinary Chinese have finally caught up with Beijing. Many Chinese people now view the lack of a new system as an example of unresponsiveness, and even indifference, from their government.

The “Economic Contract”

And that brings us to the economic contract.

When the state began to retreat in the 1990s, it permitted China’s private sector to grow and pick up some of the slack. People could try to meet their needs through the most basic private function—precautionary savings of their money. But they could also pick up slack by increasing their incomes via activities in private firms, private smallholdings, private exchanges of goods and services, and other forms of private transactions.

The state insisted that it continue to control the commanding heights of the economy—entrenching state-led oligopolies in resource sectors (such as oil and minerals), key services sectors (including banking, telecoms and insurance), natural monopolies (such as public utilities), and strategic sectors (such as defense production). But it left many other sectors to private players—for example most of agriculture and much of China’s manufacturing sector.

Xi’s team is now corroding this contract as a deliberate strategy—viewing a stronger state role in the economy as a means to deal with social and political challenges.

This means that, where Xi’s predecessors opened up space for the private sector and even brought private entrepreneurs into the Party, his team is doing much the opposite—pushing Party cadres back into private firms, taking public stakes in private companies, imposing new regulations on the private sector, and closely monitoring and cracking down on the business activities of private oligarchs.

In short, an economic contract that had seemed to be bifurcating and segmenting the public and private spheres in China is being corroded in new ways. The public role has begun to expand in fresh directions.

As I have argued elsewhere with Damien, this has much to do with the way that crony capitalism evolved in China over the last two decades.

Chinese leaders have perennially feared that corruption could destroy the Party, but when the country was poor there simply wasn’t all that much to pilfer. This changed when reforms created a windfall of opportunities to engage in rent seeking.

Xi emerged politically within that context. And he has proved himself to be a powerful advocate for Leninist organizational principles, Party discipline, and rectification in the face of such activities. This has meant that he is reversing some of the Party’s prior efforts to co-opt private actors. Instead of “co-optation,” Xi seems to prefer the heavy hand of discipline.

Just take the so-called “Three Represents,” an ideological campaign launched by one of Xi’s predecessors, Jiang Zemin. Jiang’s effort sought to expand the Party tent by bringing into it China’s most powerful businesses and private sector interests. By making the Party a safe haven for capitalism, it would, in effect, represent the entire Chinese establishment.

Or so the theory ran. As Damien and I have argued before, one unintended consequence was to blur the line between Party and business. Cadres at all levels wanted to capture the reform dividends from a booming economy awash in money. So crony capitalism became endemic. And the nominally “Communist” Party came to be seen as a venal establishment undermining the public interest.

Xi is having none of this business about empowering private interests and “broadening” the makeup of the Party. His team views the unwinding of some of these prior policies as a necessary step toward a new and, from their standpoint, more satisfactory division of roles between the public and private spheres. And so Xi is rolling back the Three Represents by injecting the Party more firmly into private business and social groups, rather than the other way around.

If Jiang’s initiative made the Party more representative of China’s establishment, Xi views the Party itself as the rightful establishment. He is favoring the public sphere—and extending its social, political, and economic reach.

XI’S BIG BET

So that defines the “big bet” at the heart of Xi’s “new deal.” He aims to pursue the new principal contradiction but within the context of a more statist, more Party-centric, more disciplined, more self-regulating, and ultimately more Leninist political system.

Can that be done? I’m skeptical.

But the test will be this: does Team Xi succeed in delivering three things to the public—cleaner governance, adaptive governance, and responsive governance—even as they strengthen the Party’s hand?

“Clean” Governance

Delivering “clean” governance will mean continuing to fight corruption but in a decidedly new way.

The Party has certainly put the public on notice that it’s serious about taking down high officials on corruption charges. Xi’s close colleague, Wang Qishan, who led this effort over the last five years, often invoked the notion that he was simultaneously fighting both “tigers” and “flies.” But while taking down “tigers”—China’s high officials—generates headlines and has political shock value, it hasn’t necessarily changed the day-to-day lives of ordinary Chinese for the better. For the ordinary citizen, the corruption that truly matters is much closer to ground level. One example is hospitals that gouge patients merely to dispense prescriptions or clinical care. Another is graft by traffic cops, or bribes to local services providers. And so on.

The Party has certainly proved that it can vanquish “tigers.” But to many, that is just Party “inside baseball.” To credibly pursue the new principal contradiction, Xi’s team will have to swat a lot more “flies,” demonstrating to ordinary citizens that they is dealing with structural factors not just individual officials, addressing petty not just high-stakes corruption, and significantly eroding the rent-seeking behavior that interferes with citizens’ daily lives.

“Adaptive” Governance

Assuring “adaptive” governance, meanwhile, will mean moving to address gaps in social services. The Party has, quite simply, not adapted well in recent decades to the changed conditions of an aging society and growing economic inequality. It’s also not proved to be very adept at crisis management, as the botched responses to various national disasters and industrial accidents—all of them accompanied by huge public anger—have shown.

A first test of adaptation will be whether Xi’s team reinvigorates various structural reforms—not just market economic reforms but also services-related reforms to pensions and healthcare, as well as labor market reforms that could enable mobility and allow citizens greater freedom to migrate legally in search of economic opportunity. A second test will be whether Xi’s various administrative reforms better prepare the state itself to deal with inevitable crises, rather than just entrenching the Party for its own sake.

“Responsive” Governance

The ultimate question, though, will be whether Xi’s “new deal” restores credibility to the Party’s argument that it can be responsive to public demands even though it is unrepresentative politically. And this is especially difficult because the constituency Xi’s new contradiction is aimed at—China’s urban middle class—is growing, while other constituencies, such as farmers, are shrinking.

And the early signs are not good. For example, China’s urban middle class demands safe and excellent schools. But this week’s headlines in China are all about an abuse scandal in a Beijing middle school that has rocked the city and angered parents nationwide. And that is just one example.

Chinese citizens don’t choose their representatives through democratic election. So feedback mechanisms between the ruled and the rulers must operate within the context of a Leninist political system run by a Communist Party in a one-Party state.

Five years from now, Team Xi is, of course, going to argue that it has succeeded in meeting public expectations and has delivered on public demands for, as Xi himself put it, “a better life.”

So it is this angry middle class that will be the Party’s toughest critics—and its most significant political challenge.

Xi’s colleague, Wang Qishan, is a voracious reader of political history. His choice of books is said to run to the works of Tocqueville, whose meditations on the French Revolution included the insight that class discontent can be a source of revolutionary upheaval. Navigating middle class distress, dislocation, and demands is surely, then, uppermost in the minds of those who designed the new “principal contradiction.” But for a one-Party state to do so seems an especially hard road to walk and a contradiction in and of itself.