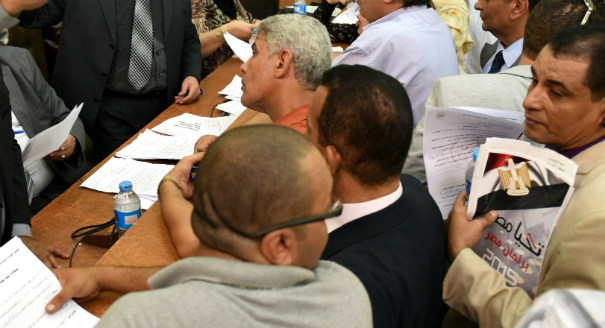

After several delays, on August 30 Egypt’s High Electoral Commission (HEC) announced the schedule of the electoral procedures and polling dates, slating two rounds of elections for October 17-19 and November 21-23. Since ousting former president Mohamed Morsi in 2013, President Abdel Fattah el Sisi has repeatedly promised parliamentary elections; one of the pillars of the post-Morsi roadmap.

Over the summer, President Sisi gradually set the stage for holding the long overdue parliamentary elections. On July 9, Sisi signed a decree amending Article 2 of the Electoral Constituencies Law, and later on July 29 issued two other amendments to the Political Rights Law and House of Representatives’ Law. He also issued another decree detailing the composition of the HEC, which opened candidate and list registration on September 1, and has reportedly approved 81 local and 6 international NGOs to monitor the elections.

But these amendments do little to allay concerns that the electoral system, which judges deemed unconstitutional twice in three years, will result in a standing parliament whose monopoly on legislative powers provides the necessary check on the executive branch. In 2012 Egypt’s Supreme Court ordered the dissolution of the parliament, and in March 2015 the Supreme Constitutional Court (SCC) issued two rulings deeming several articles of the Political Rights Law, House of Representatives Law, and Electoral Constituencies Law unconstitutional.

Subsequently, the government decided to amend only the specific articles deemed unconstitutional by the SCC rather than overhauling entire laws and building socio-political consensus around new drafts of the laws in question. Sisi amended the Political Rights Law and House of Representatives law to adjust campaign spending rules and allow Egyptians with dual nationality to run for parliament. But the distribution of individual seats per district in the new Constituencies’ Law, the previous version of which violated the constitution’s requirement of “fair representation of the population and governorates and equitable representation of voters,” preserves the mixed electoral system while changing the individual districts and seat distributions. The amendments decrease the total number of individual districts from 237 to 205 and raise the number of individual seats from 420 to 448 (or 75 percent of total seats). The four closed lists and their 120 seats (20 percent of the total) remain unchanged, as with the 28 (or 5 percent of seats) appointed by the president.

Though the government amended specific articles of these laws per the SCC’s ruling, these laws can still be challenged because the SCC’s mandate is to review specific articles raised before the court, as opposed to scrutinizing laws in their entirety. In the 2012 constitution, Article 177 granted the SCC the power to review draft electoral laws before they were enacted, to ensure their constitutionality and to avoid the dissolution of parliament. But the 2014 constitution, however, removed this provision. In addition, the SCC is no longer required to rule on the constitutionality of election laws within five days of hearing a case, as Sisi repealed this provision (added by interim president Adly Mansour in 2014) on July 28. This not only means that the SCC is under no obligation to make a swift decision on the constitutionality of a law, but this decision could be made after elections and a parliament has already been seated.

In the absence of a sitting parliament, Presidents Mohamed Morsi, Adly Mansour, and Abdel Fattah el-Sisi have held both executive and legislative powers, issuing laws by presidential decree. According to the vaguely-worded Article 156 of the 2014 constitution, the next elected parliament should review laws enacted in the absence of parliament within fifteen days of its first session for them to be considered legal. But hundreds of laws have been issued since Morsi’s ouster in July 2013—on topics ranging from trade and investment, terrorism, and civil rights—so meeting this requirement is beyond parliament’s capacity. Article 156 leaves the door wide open to the tacit rubber-stamping of most if not all presidential decrees without much debate or discussion. The implications are staggering, as over two years of policies and laws of a controversial presidency could go unchecked by parliament.

In addition, the repeated delaying of parliamentary elections has raised questions about the government’s sincerity to hold elections at all or seek consensus before enacting crucial laws, including those relating to elections. From the outset, political parties have voiced their concerns and disapproval of electoral laws that favor individuals over parties, benefiting pro-Sisi individuals and amounting to a return to the Mubarak era. Several parties submitted their comments and suggestions to the government and sought to use the elections delay to overhaul the electoral laws. However, the government claimed the parties’ recommendations were not compatible with SCC rulings and declined to include them in the amended laws.

But Egypt cannot afford a parliament that rubber-stamps Sisi’s decrees—or one that does not exist at all. Even though some estimates indicate that nine out of ten Egyptians approve of Sisi’s performance, his mismanagement of the political sphere is one of the main drivers of the growing political apathy and uptick in violence among youth groups. Sisi has long claimed to be apolitical, labeling politics as a luxury that risks further societal divisions at a time when Egypt needs unity. Ultimately, however, Sisi’s policies of stifling dissent and cracking down on opponents—including his regime’s assault on media and human rights organizations—are increasingly alienating the population. And the current legislative and judicial climate in Egypt does nothing to prevent the government from enforcing unconstitutional laws, even if they are later struck down when the SCC finds them unconstitutional. In the meantime, the dysfunctional situation allows the government to trample on individuals’ rights, restrict freedoms, and waste precious time that Egypt can’t afford to lose.

Ahmed Morsy is an Egyptian researcher and a PhD candidate at the School of International Relations, University of St. Andrews. Follow him on Twitter @ASMorsy.