Introduction: Why Europe Needs Africa (and Africa Needs Europe)

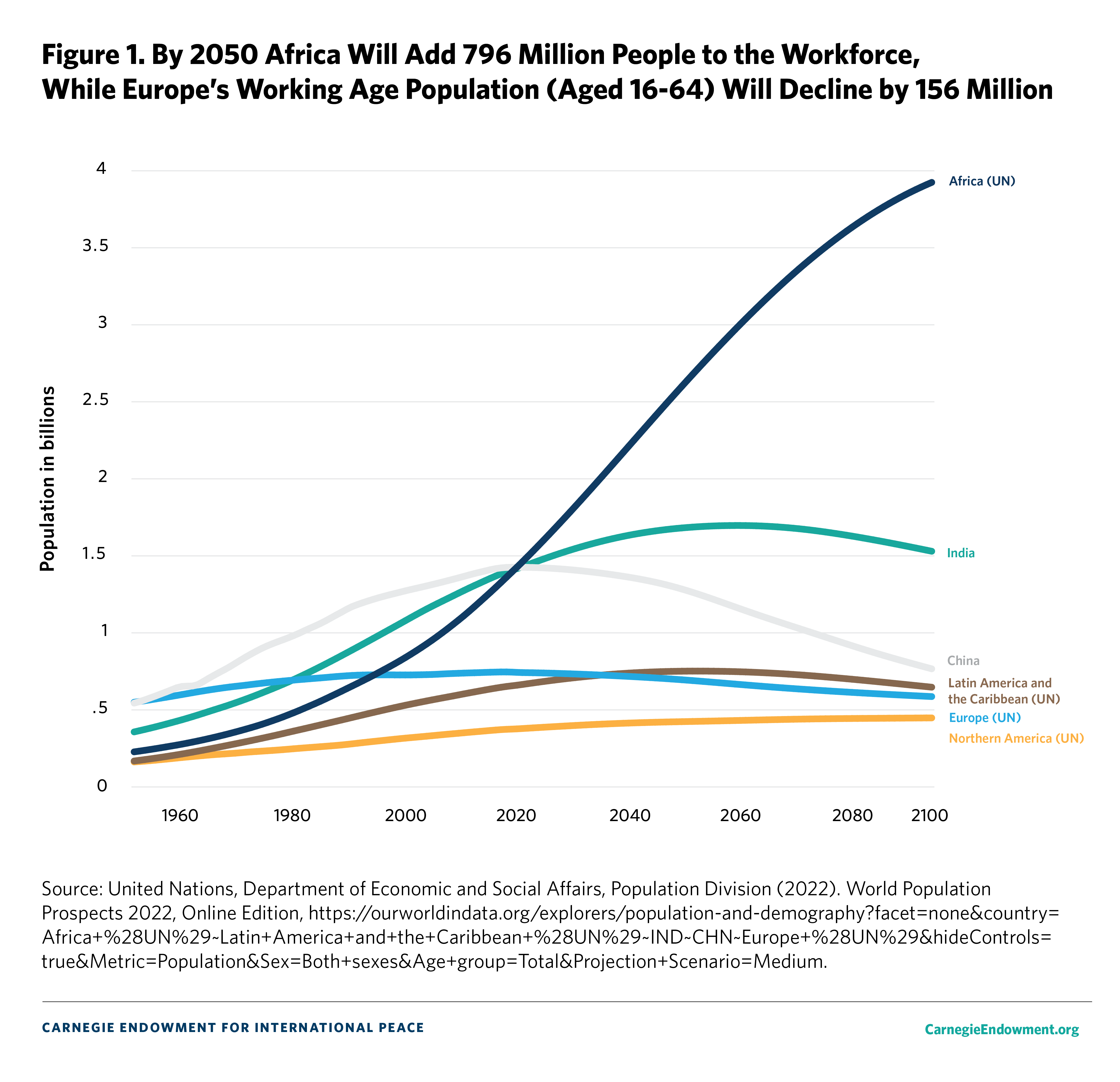

In 2017, Africa’s population under twenty-five years old surpassed the total population of Europe. By 2050, Africa will have added 796 million people to the workforce, while Europe’s working-age population (aged sixteen to sixty-four) will decline by 156 million.1

Europe is aging while Africa’s youth population booms.

This demographic transformation is perhaps the defining shift that could recast the fortunes of the two continents, which are separated, at the closest point between Morocco and Spain, by just 14 kilometers (less than 9 miles).2

Labor shortages and pension costs are already impacting the credit ratings of European countries,3 while the massive demand for employment in the African continent will have significant implications—positive and negative—in terms of migration, stability, future market potential, and economic dynamism.

However, the demographic shift (highlighted in figure 1) is not the only long-term trend that could shape the Africa-Europe partnership.

Managing climate change, biodiversity, health security and pandemic preparedness, migration, and the rapid pace of technological innovation requires cooperation across borders.

In truth, almost all of the major threats and opportunities that Europe could face in the next century will require cooperation with Africa, either to limit harm or maximize opportunities.

Europe needs Africa, at least as much as Africa needs Europe.

Yet, the unspoken assumption underpinning Africa-related decisions of Europe’s leaders—both inside and outside of the European Union (EU)—is that Europe is supposedly more advanced and that African countries are laggards. They are beset with problems, and need to be more like European countries in order to converge with a better way of living and managing their societies. This is borne out in the lexicon of “developed” and “developing” countries, in the indices regularly published by international institutions and think tanks, and in the objectives and goals of Europe’s development cooperation with Africa.4

The premise of this compilation is that the European policy making community needs to flip this narrative and recognize that there are different development paths that are informed by context-specific factors, as well as common challenges that different countries and regions will need to grapple with together. From that perspective, cooperation between Africa and Europe should build on both continents’ strengths to identify converging interests, compatible visions, and potential synergies.

Thomas Kuhn, in his seminal book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, introduced the concept of a paradigm shift. Kuhn showed that “normal science”—periods of steady incremental progress in which researchers worked largely to validate their current paradigm—were punctuated by periods of disruption in which the old paradigm failed and a new one emerged.

The principle can be applied to policymaking and politics. Ideas harden into norms around which politicians and policymakers build careers, institutions build treaties, and media outlets build narratives. This is the status quo until these norms become obsolete and a new one emerges.

One can argue that the norms which have shaped the careers of many current policymakers are now out of date. In April 2023, U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan outlined a “new Washington consensus,” implying that the old one, which had shaped a generation of economic and foreign policy making, had passed.5

A wave of populism led to the UK’s Brexit referendum, the election of former U.S. president Donald Trump, and the emergence of right-wing political movements across Europe, a trend borne out in the 2024 European Parliament elections. The same wave has been accompanied by the growing influence of China, increasing geopolitical competition between the United States and China, and renewed confidence among African leaders and their electorate on the global stage.

At the January 2024 Italy-Africa Summit, the chair of the African Union Commission called specifically for a “paradigm shift” in Africa-Europe relations.6

While it is clear that the old order is out of date, there is not yet a clear successor. Indeed, the moment may be less a paradigm shift and more an “interregnum”: a period of transition between the collapse of an old hegemony and the establishment of a new one, during which the old powers lose their legitimacy and new ones have not yet gained enough power or acceptance to establish themselves.7

Regardless of the theoretical underpinning, policymakers in Europe and Africa find themselves navigating a new world, trying to find a path that protects and sustains their interests and values. And while many of these are shared, the risk is that we fall into a “beggar thy neighbor” approach whereby nations turn inward, pursuing their own domestic economic and strategic interests in a world where international cooperation on global challenges like climate change and pandemic preparedness are needed more than ever.

Europe’s responses to two major challenges—the COVID-19 pandemic, when it initially hoarded vaccines, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, when it took its focus from Africa and diverted resources and political attention to Ukraine—suggest this is a significant risk. Evidence of African countries courting Russia and other powers to meet their food, energy, and security needs show that this risk is not one-sided.

There is, however, a significant opportunity for the two continents to navigate these choppy waters together.

In February 2022, leaders of the EU and the African Union (AU) convened a summit to discuss the future of continental relations.8 European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen had previously stated that the relationship is a “partnership of equals,” whereby the two continents work together to tackle common challenges.9

That rhetoric has been accompanied by project-level commitments and financial pledges of leveraged private capital. However, the rhetoric has been met with much skepticism from African leaders, who are looking for the delivery of unfulfilled financial commitments and a meaningful seat at the global decisionmaking table.

African leaders, buoyed by the reality that they can choose who they partner with, are increasingly bullish about their role on the international stage. It is no secret that China has spent the past two decades building influence on the continent through diplomacy and major infrastructure investments, committing an estimated $153 billion between 2000 and 2019 to African public sector borrowers.10 India, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Türkiye are also taking an increasing interest in the region through diplomatic, military, and economic cooperation.

At the same time, leaders such as former Senegalese president and 2022 chairperson of the AU Macky Sall and Kenyan President William Ruto have called for reforms in global economic governance to reflect Africa’s increasing role in the global economy—including successfully campaigning for an AU seat at the G20,11 reform of the credit rating agencies,12 and shifts in the governance of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.13

The skepticism of some African stakeholders is warranted. Trading relationships between Europe and Africa are highly imbalanced, echoing a postcolonial extractive model. In 2021, 68 percent of goods exported from Europe to Africa were manufactured goods. The majority (65 percent) of imports from Africa were raw materials and energy.14

The February 2022 EU-AU Summit was strong on rhetoric, and headline commitments were significant. The EU pledged €150 billion in investments in Africa over seven years—a scale that is clearly framed to rival China’s Belt and Road Initiative. But African leaders, such as South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, expressed skepticism in light of previous commitments on climate finance that were not delivered. In a post-summit interview,15 Ramaphosa signaled that while Africa welcomed European investment, Africa would remain free to work with other partners.

Less than two weeks later, the partnership faced a significant test. Russian President Vladimir Putin launched an invasion on Ukraine, a move that reignited the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the transatlantic alliance and led to unprecedented steps from EU member states—but illustrated the complexity of Africa-Europe relations.

Four UN General Assembly votes—three condemning the actions of Russia and a fourth to expel Russia from the UN Human Rights Council—passed by majority,16 but in each case, more than half of the countries that abstained from the vote were African. European countries were taken by surprise over Africa’s perceived lack of support at the General Assembly.17

In June 2022, then Swedish foreign minister Ann Linde told the European Council on Foreign Relations that she discussed the issue with her South African counterpart, comparing Europe’s support for the anti-apartheid movement with Africa’s lack of support for Europe over Ukraine.18

African leaders then played an active role in 2023 by sending a presidential peace delegation to Kyiv. Notably, the nonalignment of many African countries positioned them to be neutral brokers in a peace deal.19

In late 2023, following Hamas terror attacks on Israel, von der Leyen’s strong support for Israel contrasted with a number of African countries’ strong condemnation of Israel’s military operation in Gaza—most notably with the position of South Africa, which referred Israel to the International Court of Justice.20 Since then similar divisions between African and European countries have been visible in UN General Assembly votes on Palestine.21

Notwithstanding these fault lines, there are significant potential benefits in getting the Africa-Europe partnership right (and risks in failing to do so). Both African and European policymakers are attuned to the risks of large numbers of young people without job opportunities and impacted by climate-induced weather events migrating in large numbers.

As the European electorate focus on domestic priorities and European leaders make the case for greater European sovereignty,22 policymakers should consider the potential mutual benefits of greater cooperation.

The Case for a Strategic Partnership

While geography, history, and politics will play a critical role in the future of this relationship, the starting point lies in the greatest resource of the two continents: their people.

In Europe, the balance between the working age population and those dependent on them has been declining since 1985, and that trend is accelerating. As Europeans live longer, the cost of healthcare, pensions, and housing increases—costs that will be borne by younger generations that are fewer in number. Because there are fewer economically productive people to generate the necessary wealth and public revenues to support services, such as education, that are so critical to social mobility, many—young and old—are seeing fewer opportunities. This, in turn, is fueling a political nativism that is already hampering trade, migration flows, and international cooperation.

The UK’s 2016 referendum on leaving the EU and the significant growth of populist and in some cases extremist right-wing parties in Belgium, France, Italy, and Sweden are both the symptoms of a structural transformation where some parts of European society are not benefiting from globalization. But it is also a movement driven by nostalgia. This is undoubtedly, in part, driven by Europe’s aging population.

Signals from African leaders, in contrast, point to a continent looking forward. A long-term development plan (in the form of the AU’s Agenda 2063) aims to create a pan-African single market, freedom of movement, and flagship infrastructure initiatives such as a high-speed rail network—a plan that mirrors the early ambitions of the EU.23 Yet, it is a continent with major challenges when it comes to conflict, poverty, and vulnerability to economic and climate shocks.

The reality is that by working together, both continents can address the common challenges they face. The twenty-first-century economy requires people with technical skills and characteristics that can navigate rapid and constant change: resilience, determination, and an ability to collaborate. European countries, with their strong education systems and technical knowledge, lack sufficient numbers of young people with the dynamism to sustain the twenty-first-century economy.

Africa has the youngest population in the world, a population that is increasingly urban and entrepreneurial. Countries, corporations, and cultural trendsetters recognize the continent’s investment potential. But what Africa has in terms of young people and cultural dynamism, it lacks in terms of infrastructure and investment to develop technical skills and build effective markets. Europe has that capital, experience, and technical skills.

A Change of Mindset

With the right frameworks and standards, Africa could supply the necessary labor to address Europe’s challenges with aging. Europe on the other hand could help provide the financial capital needed to support Africa’s human capital and hard infrastructure.

But efforts to maximize the benefits of such a partnership need changes from both parties. Europe will have to reframe fractious debates on migration in ways that are both pragmatic and politically salient. To succeed, Africa will need to address issues such as the high cost of capital and low level of investment, governance service gaps, and market fragmentation.

Achieving this new outlook requires a reframing of the nature of the partnership, beginning with prevailing narratives that shape the public debate.

Europe traditionally sees its role on the international stage in three ways: it is a global trade power and a provider of development aid; a political and security actor, supporting regional security through bodies such as the AU; and a normative power, supporting human rights and democracy, regional integration, and multilateral organizations.24

But in a world of increasing geopolitical competition, with transnational issues such as climate change, migration, and technology taking a prominent role, Europe has found itself in an increasingly complex environment where norms and standards that Europe sees itself as traditionally upholding—such as human rights and democracy—are being weaponized. For example, in the wake of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, European policymakers are increasingly concerned that they are losing a battle of hearts and minds in Africa, and they have proposed a more transactional approach to European aid programs.25 By failing to live up to its own standards, or simply misunderstanding how it is perceived in the Global South, Europe risks its unique added value of standing up for human rights and using soft power to do so.

In Africa and across the Global South, views of Europe are shaped by history but also by present behavior. Europeans see their role as a standard setter on environmental and governance norms, so access to the EU’s market has become contingent on environmental and governance standards. However, some in the Global South see these standards as self-serving protectionism. For example, in 2016, the EU pursued a heavy-handed approach to border protection in the Mediterranean Sea; that year, 3,800 migrants died trying to reach Europe. In response, Ethiopian policymakers noted how the EU’s values-based approach to foreign policy had been devalued. The EU’s role in hoarding vaccines at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and locking African countries out of access was seen as hypocrisy—and was not remedied by the EU’s steps to donate vaccines or fund COVAX,26 the World Health Organization’s initiative to procure vaccines for the Global South. Steps to divest from financing liquefied natural gas in emerging markets while including gas in the EU’s Sustainable Finance Taxonomy is a more extreme example.27

On the African continent, Europe’s cultural exports—such as major football teams—are ubiquitous. But Europe’s development cooperation presents a more nuanced picture. A recent poll of African young people showed that 76 percent believed that China brings a positive influence to the continent.28 They considered Europe’s cooperation to be of higher quality while valuing China for fast decisionmaking and timely completion of projects.29 China’s high visibility infrastructure strategy clearly has an impact on perceptions, while Russia’s disinformation campaigns have negatively shaped Africans’ views of European and U.S. foreign policy, with many blaming sanctions on Russia for Africa’s food price inflation.30 There is, however, a strong argument that Europe’s positive role on the continent lacks visibility. For example, Ethiopia’s Industrial Parks are funded by the EU, but awareness of that support is limited.31

On the European continent there remains a widely held belief that Africa is a continent of underdevelopment, poverty, and conflict, and among policymakers, the continent is frequently viewed as an aid program recipient rather than a strategic partner—a viewpoint that belies the diversity, vibrancy, and nuance of the continent. Economic migrants contribute more economically to their host states than native populations—and migrant remittances to poor countries now eclipse aid flows.32 Yet, migrants are seen as a drain on the system. European citizens increasingly see aid as ineffective and view Africans as increasingly “ungrateful” for European generosity.33

Furthermore, many policymakers still see aid as an instrument of control, used throughout the post–World War II era to impose harmful austerity and policy conditions. AidData’s 2021 Listening to Leaders survey demonstrates a disconnect between the priorities of leaders of so-called “recipient” countries and how donors spend their money: Global South leaders prioritize education and employment, while donors prioritize inequality and gender.34

Despite the efforts of reformers within European member states and institutions, budgetary planning and bureaucracy mean change happens slowly. In addition, Europe’s colonial history still looms large. Anti-French sentiment in West and Central Africa is part of a wider trend that views Europe’s role in Africa as negative—a trend that has played into a series of coups in the region. Russia under the former Soviet Union provided tangible support to the decolonization movement in vast parts of eastern and southern Africa, and then provided support to the newly independent countries until the collapse of the Soviet Union. This history is very much alive in the minds of many African policy, media, and intellectual elites who studied in the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russia.35

In Africa the trend toward self-determination is clear. Agenda 2063, the AU’s blueprint for turning the continent into an economic powerhouse, was agreed to in 2015.36 A central pillar of this plan is the African Continental Free Trade Area, which entered into force in May 2019. Trading under the agreement began in January 2021 and is projected to raise incomes by 7 percent by 2035 and lift 40 million people out of extreme poverty.37

But this optimism belies the complexity of implementing these plans, the significant economic and social headwinds faced by African countries buffeted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and inflation and debt sustainability concerns. Forty percent of African countries are in or are at high risk of debt distress.38 Youth unemployment remains a major concern; a third of South Africa’s population is unemployed, and the pan-African unemployment rate has increased significantly since 2015. And conflict remains a major challenge in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Ethiopia, Libya, northern Mozambique, Sudan and South Sudan, and countries in the Sahel.

These differential and nuanced reflections on the nature of the relationship between both continents must be addressed and the potential of a partnership made clear. To break from these narratives requires a different approach, one that moves beyond summitry and institutional negotiations and builds networks of creativity, commerce, problem-solving, and trust.39

The good news is that these relationships, initiatives, and ideas already exist in abundance. The aim of this compilation is to take some of the major challenges—migration and remittance flows, climate change and the energy transition, the investment in and governance of global public goods, and the management of digital technology and regulation—and reframe the opportunities and potential for collaboration.

Each of the authors takes this as a starting point, identifies examples of good practices that could be reflected and supported through institutional cooperation between Europe and Africa, and outlines where new kinds of approaches could not only deliver short-term impacts but also build trust, serve mutual interests, and meet the challenges the continents face today.

Jonathan Glennie and Hassan Damluji propose a new form of development cooperation, based not on charity or fighting poverty but on circular cooperation: partnerships based on consistent iteration, learning, and mutual problem-solving that offer potential for greater impact and improved trust and dignity between Europe and Africa.

Saliem Fakir lays out the opportunities for economic transformation presented by the energy transition and the geopolitical fault lines that need to be bridged to seize them. He makes the case that the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act and the EU’s Green Deal are marked departures from global climate diplomacy toward state-led industrial policy; for the first time in a generation, the desires of the United States, Europe, and Africa to transform their economies and energy systems align. As such, he makes the case that Europe should leverage its assets and capabilities—through market-making regulation and development finance institutions—to increase investment in African climate infrastructure and make joint action on climate diplomacy a central pillar of the continent’s climate strategy.

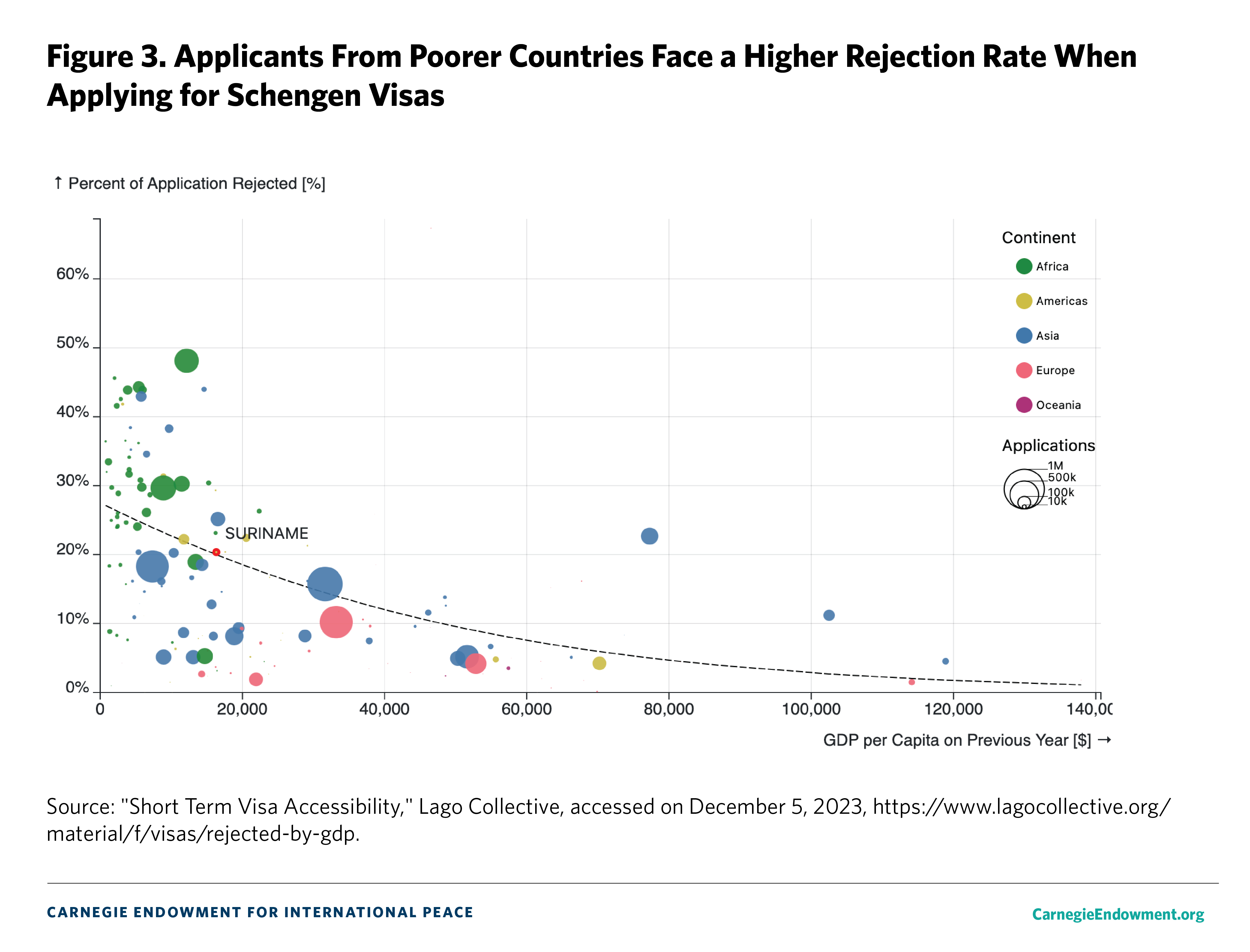

Marta ForestiandDavid McNair argue that debates on human mobility should move from fractious national debates about keeping people out and instead focus on enabling spaces of connection and collaboration. They highlight the ways in which creatives from the fashion, design, and music industries are collaborating across borders to create a vibrant economic and cultural landscape. But to build these bonds of creativity requires addressing visa policies. They propose a new, restricted, skills-based visa system to deepen these connections and investment in African and European creative cities partnerships.

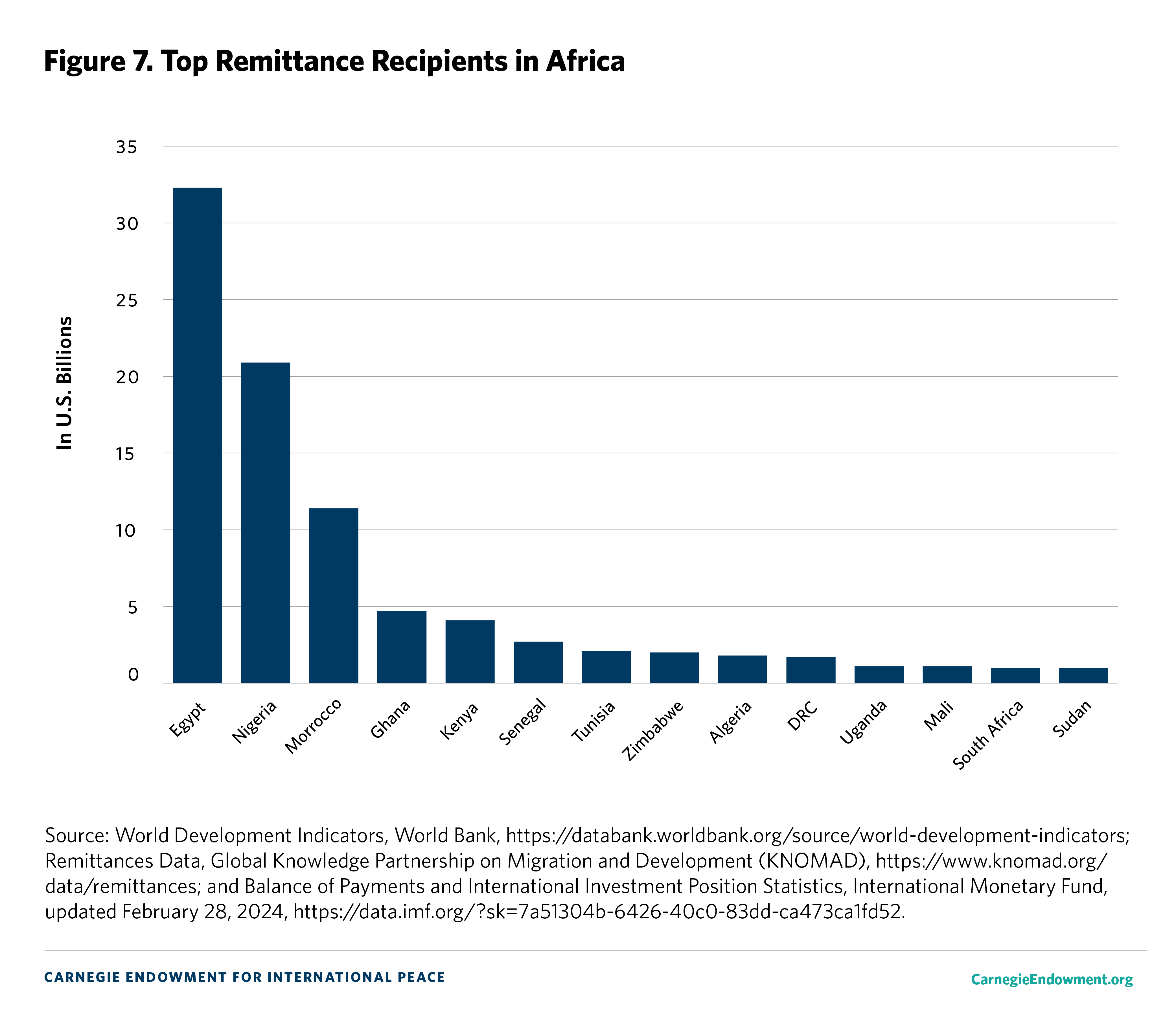

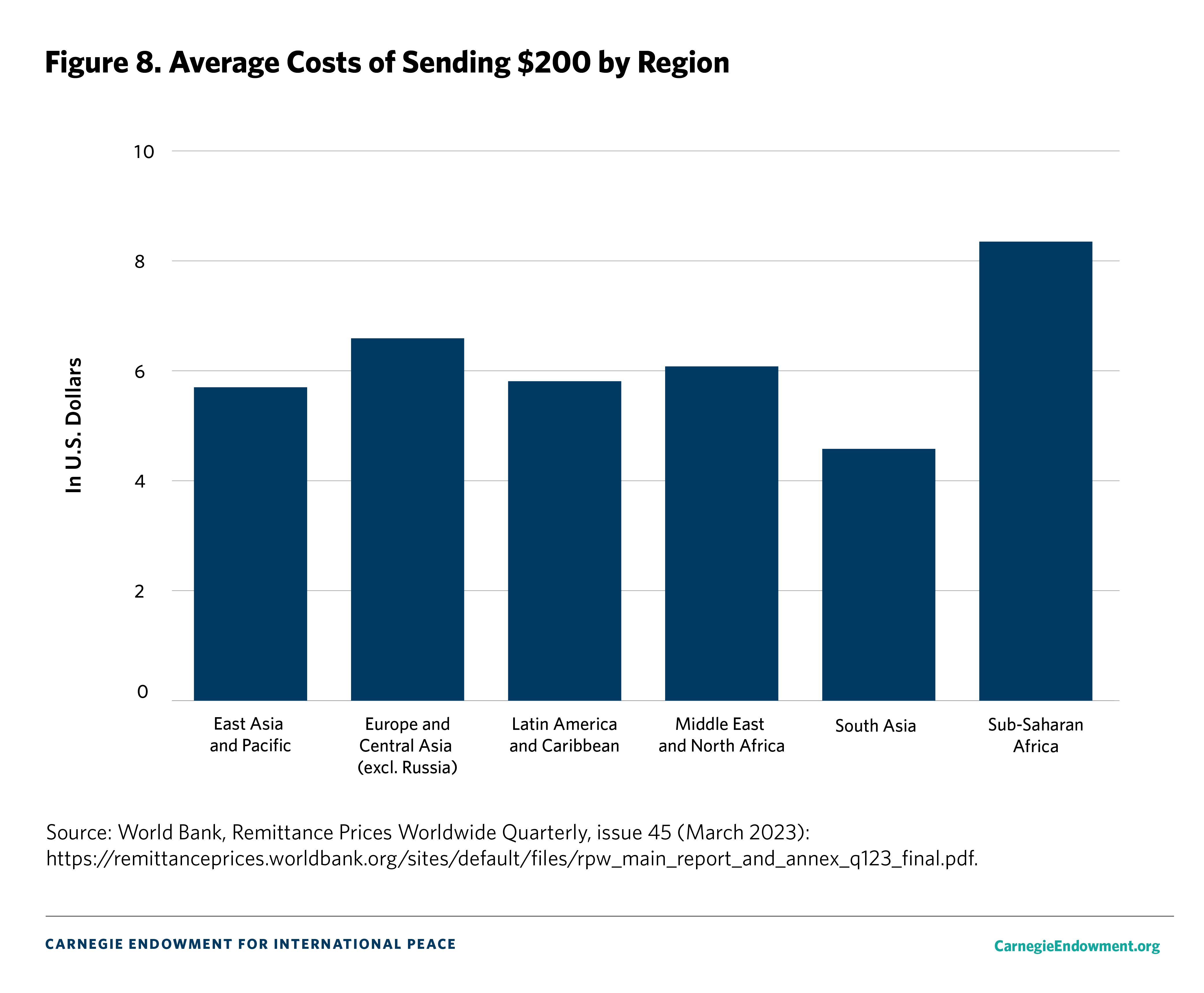

Ottilia Anna Maunganidze argues that perhaps the most significant outcome of migration between Europe and Africa is financial flows in the form of remittances, which now eclipse official development assistance in volume. While Europe has made significant progress in reducing remittance costs, a number of challenges remain, not least the cost of some remittance corridors within Africa. She argues for the sharing of knowledge and technology and the harmonizing of international rules governing remittance flows.

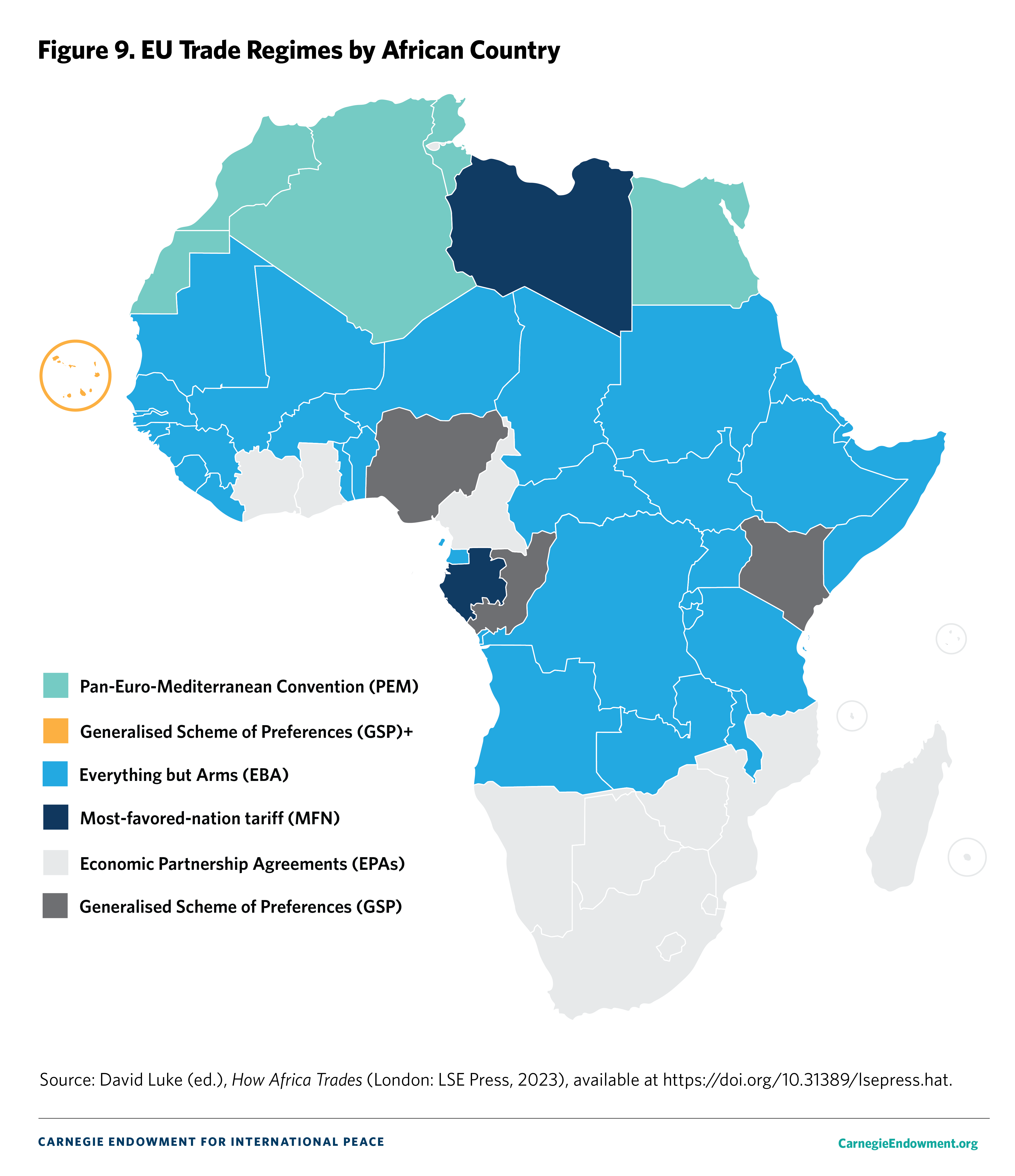

David Luke argues that Europe and Africa are on course for a collision in trade policy because of the ways in which Europe’s patchwork of trade agreements across the continent are inconsistent with Africa’s ambition for a continental free trade area. He argues that the EU should grant duty-free, quota-free, unilateral market access to all African countries, with a unified rules-of-origin regime for a transitional period benchmarked against milestones in Africa’s free trade area implementation and the gains emerging from it.

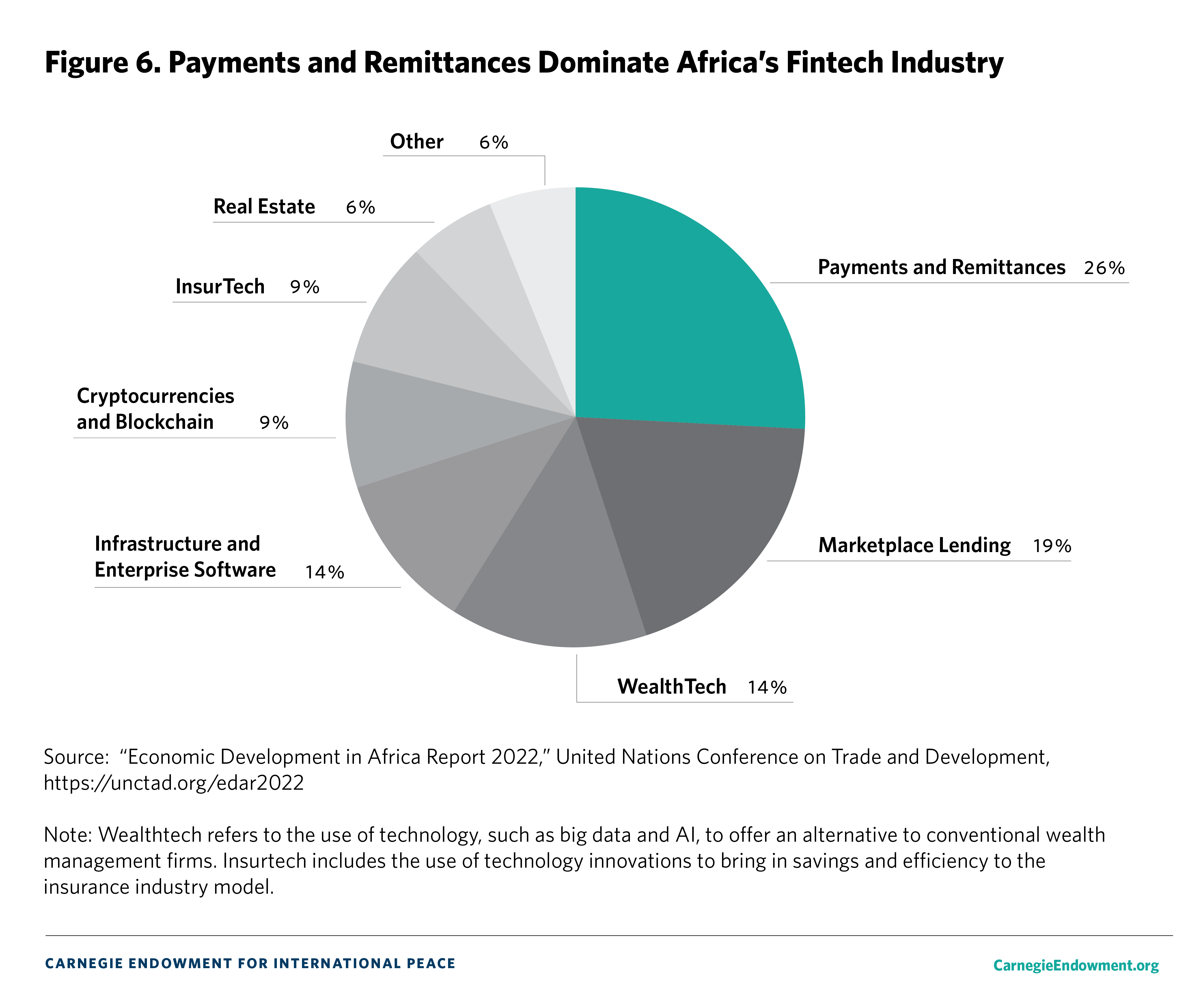

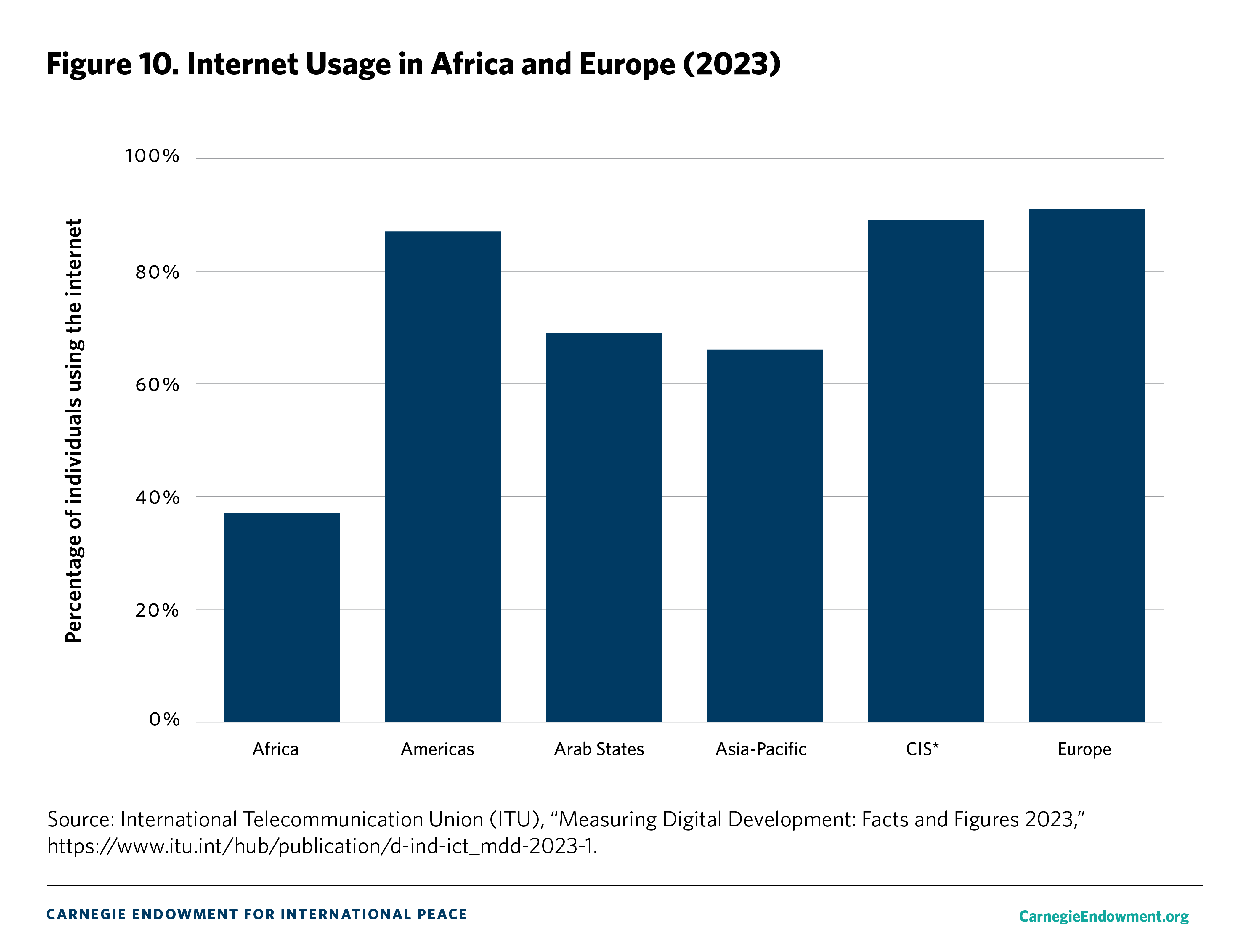

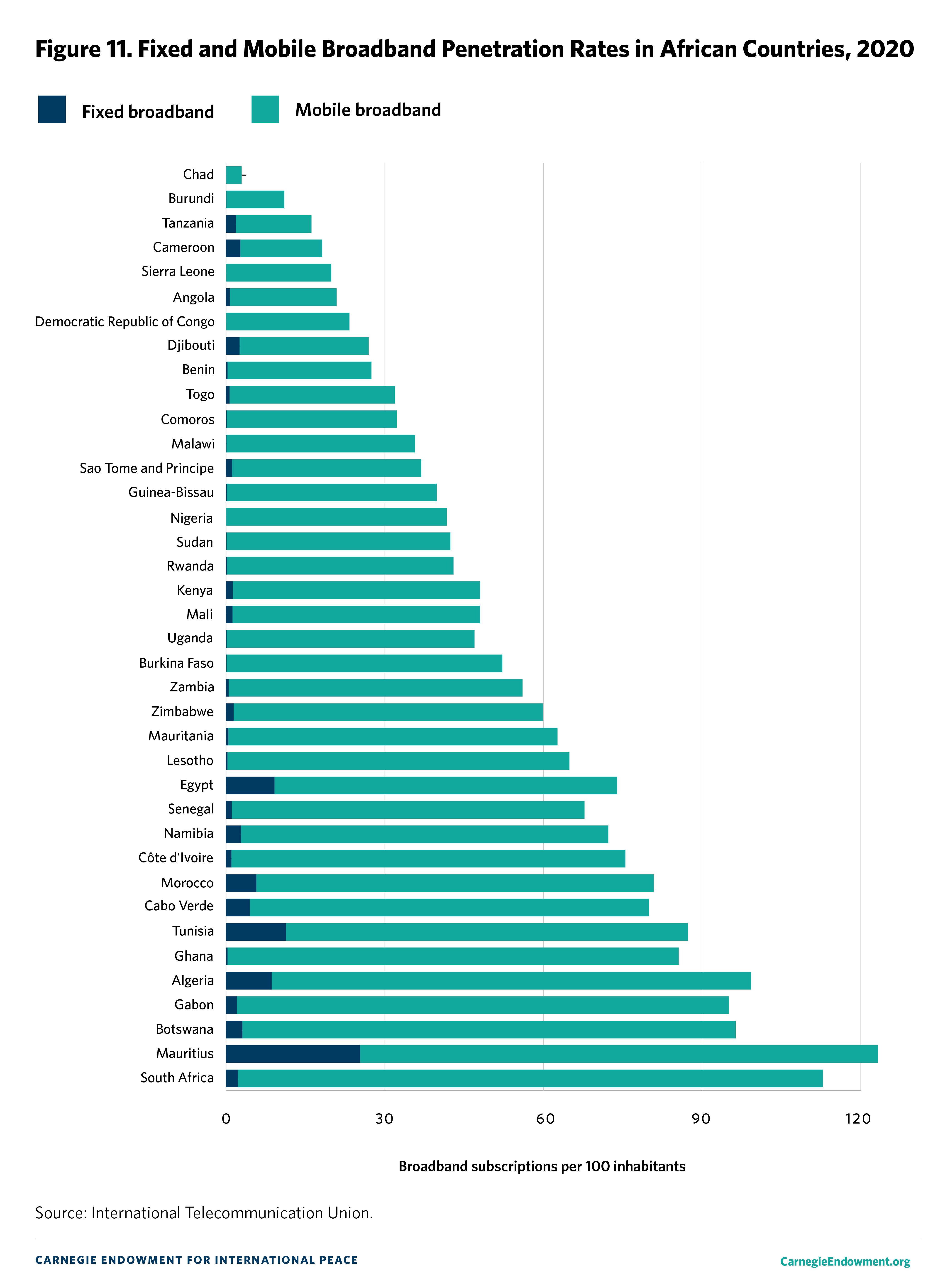

Jane Munga argues that the digital economy will shape the future of both continents. But in a world where technology and data are increasingly weaponized, Europe and Africa can work together on common regulation and frameworks governed by principles of freedom and prosperity. Europe can bring its experience in regulations and building common markets, while Africa can bring its digital innovation and the potential for widespread and rapid uptake of new digital technologies.

Fred Ngoga concludes the compilation by reminding readers that any partnership between Africa and Europe is made up of millions of personal experiences. He tells human stories to make the case that policymakers should listen first to the experiences of individuals navigating the legal, geographic, and institutional barriers between Africa and Europe and take a human-centered design approach to new policy frameworks.

The common thread that lies in all of these contributions is a need to step outside of current modes of thinking about geopolitics, development cooperation, and diplomacy and instead consider the ways in which a genuine partnership could build on what each party brings to navigating the current era of disruption and confusion.

Our hope is that our modest contribution helps politicians and policymakers, who carry a heavy burden of responsibility, to think differently about these problems.

About the Authors

David McNair is a nonresident scholar in Carnegie’s Africa Program and is the executive director at ONE.org.

Kyla Denwood is a research assistant in Carnegie’s Africa Program.

Acknowledgments

This compilation was edited by David McNair with guidance from Zainab Usman, the director of the Africa Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Research and coordination support was provided by Kyla Denwood, Maxwell Clegg, and Andrew Danik.

The essays were peer reviewed by Frances Z. Brown, Mario Pezzini, and Bright Simons.

Haley Clasen copyedited the series. Alie Brase managed communications.

Two roundtable discussions informed the series. Participants were: Olumide Abimbola, Faten Aggad, Lizza Bomassi, Nathalie Delapalme, Kyla Denwood, Saliem Fakir, Marta Foresti, Jonathan Glennie, Faizel Ismail, David Luke, Jane Munga, Fred Ngoga, and Francesco Siccardi. David McNair would like to thank the authors and reviewers for their work and patience throughout the process. He would also like to extend special thanks to Amal Kaoua and Fiadh Kaoua-McNair.

Notes

1 Mayowa Kuyoro et al., “Reimagining Economic Growth in Africa: Turning Diversity Into Opportunity,” McKinsey Global Institute, June 5, 2023, https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/reimagining-economic-growth-in-africa-turning-diversity-into-opportunity; and “Population by Broad Age Group, 1950–2100,” Our World in Data, accessed November 29, 2023, https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/population-and-demography?facet=none&country=Africa+%28UN%29~Europe+%28UN%29&Metric=Population&Sex=Both+sexes&Age+group=Total&Projection+Scenario=None. Youth is defined as under the age of twenty-four. In 2017, Europe (defined as the UN region) had a total population of 744.4 million. Africa (UN region) had a population under twenty-four years old at 759.9 million.

2 The closest point between Europe and Africa is between Morocco and Gibraltar, the latter of which is considered a British Overseas Territory by the UK. At the time of writing, negotiations on Gibraltar’s relationship with the EU continue following the UK’s withdrawal from the EU.

3 Mary McDougall, “Ageing Populations ‘Already Hitting’ Governments’ Credit Ratings,” Financial Times, May 17, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/f434c586-db1f-4d81-8b29-989db5c78f72.

4 For example, Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, which highlights perceptions of bribery or misappropriation of public funds, regularly ranks African countries as most corrupt while awarding international financial centers that are widely recognized to facilitate grand corruption. “Corruption Perceptions Index,” Transparency International, 2022, https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022.

5 “Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan on Renewing American Economic Leadership at the Brookings Institution,” White House, April 27, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/04/27/remarks-by-national-security-advisor-jake-sullivan-on-renewing-american-economic-leadership-at-the-brookings-institution.

6 Angela Giuffrida and Lorenzo Tondo, “African Union Commission Calls for ‘Paradigm Shift’ at Italy-Africa Summit,” Guardian, January 29, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/jan/29/italy-africa-summit-moussa-faki-giorgia-meloni.

7 Milan Babic, “Let’s Talk About the Interregnum: Gramsci and the Crisis of the Liberal World Order,” International Affairs 96, no. 3 (May 2020): 767–786, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz254.

8 Building on half a century of declarations and summitry beginning with the Yaoundé Convention in 1963 and the Lomé Convention in 1975, the sixth EU-AU Summit occurred against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which Africa had been largely excluded from timely access to vaccines.

9 David Herszenhorn, “Von der Leyen Ventures to the Heart of Africa,” Politico, December 8, 2019, https://www.politico.eu/article/european-commission-president-ursula-von-der-leyen-ventures-to-the-heart-of-africa-ethiopia-african-union.

10 Zainab Usman, “What Do We Know About Chinese Lending in Africa?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 2, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/06/02/what-do-we-know-about-chinese-lending-in-africa-pub-84648.

11 David McNair, “Seats at the Table: How Europe Can Address the International Democratic Deficit,” European Council on Foreign Relations, October 24, 2022, https://ecfr.eu/article/seats-at-the-table-how-europe-can-address-the-international-democratic-deficit.

12 “African Governments Say Credit-Rating Agencies Are Biased Against Them,” The Economist, May 25, 2023, https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2023/05/25/african-governments-say-credit-rating-agencies-are-biased-against-them.

13 David McNair, “Global Economic Turmoil Calls for a Modernized Global Financial Architecture to Address Needs of the Most Vulnerable Countries,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, November 15, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/11/15/global-economic-turmoil-calls-for-modernized-global-financial-architecture-to-address-needs-of-most-vulnerable-countries-pub-88400.

14 “Africa-EU—International Trade in Goods Statistics,” Eurostat, February 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Archive:Africa-EU_-_international_trade_in_goods_statistics.

15 “EU-AU Summit: President Cyril Ramaphosa Says Government’s Key Focus Is on Job Creation,” SABC News, February 19, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fh0VV3k8Vms.

16 These votes were passed on the following dates: March 2, 2022; March 24, 2022; April 7, 2022; and October 12, 2022. For more on African countries’ involvement in the Ukraine war, see Catherine Nzuki, “Africa’s Peace Delegation: A New Chapter for Africa and the Ukraine War,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 16, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/africas-peace-delegation-new-chapter-africa-and-ukraine-war.

17 In June 2022, Senegalese President and AU chair Macky Sall, along with AU Commission Chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat, visited Russian President Vladimir Putin in Sochi. The meeting focused on a resolution to the Ukraine conflict and the food security implications for Africa. But Sall notably failed to condemn Russia’s actions in Ukraine. “Putin Meets African Union Chief Macky Sall in Sochi,” China Global Television Network, June 3, 2022, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2022-06-03/Putin-meets-African-Union-chief-Macky-Sall-in-Sochi-1azdhwv9SjC/index.html.

18 “Annual Council Meeting 2022,” European Council on Foreign Relations, June 19, 2022, https://ecfr.eu/event/annual-council-meeting-2022.

19 Catherine Nzuki, “Africa’s Peace Delegation: A New Chapter for Africa and the Ukraine War,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 16, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/africas-peace-delegation-new-chapter-africa-and-ukraine-war.

20 Nils Adler and Alma Milisic, “ICJ Updates: Court Orders Israel to Prevent Acts of Genocide in Gaza,” Al Jazeera, January 26, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/liveblog/2024/1/26/live-icj-to-issue-preliminary-ruling-in-south-africa-genocide-case-against-i.

21 UN Press Office, At Emergency Special Session, General Assembly Overwhelmingly Backs Membership of Palestine to United Nations, Urges Security Council Support Bid. 10 May 2024. https://press.un.org/en/2024/ga12599.doc.htm

22Emmanuel Macron and Olaf Scholz, Macron and Scholz: we must strengthen European sovereignty, Financial Times, 27 May 2024. https://www.ft.com/content/853f0ba0-c6f8-4dd4-a599-6fc5a142e879?shareType=nongift

23 “Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want, Framework Document,” African Union, September 2015, https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/33126-doc-framework_document_book.pdf; and “Goals & Priority Areas of Agenda 2063,” African Union, https://au.int/en/agenda2063/goals.

24 Rosa Balfour, Lizza Bomassi, and Marta Martinelli, “The Southern Mirror: Reflections on Europe From the Global South,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 29, 2022, https://carnegieeurope.eu/2022/06/29/southern-mirror-reflections-on-europe-from-global-south-pub-87306.

25 Vince Chadwick, “Exclusive Internal Report Shows EU Fears Losing Africa Over Ukraine,” Devex, July 22, 2022, https://www.devex.com/news/exclusive-internal-report-shows-eu-fears-losing-africa-over-ukraine-103694.

26 “We Have Enough COVID Vaccines for Most of the World but Rich Countries Are Stockpiling More Than They Need,” STAT, December 13, 2021, https://www.statnews.com/2021/12/13/we-have-enough-covid-vaccines-for-most-of-world-but-rich-countries-stockpiling-more-than-they-need; and GAVI, “Team Europe Dose-Sharing: Nine Additional EU Member-States Support Lower-Income Countries Through COVAX,” ReliefWeb, November 29, 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/world/team-europe-dose-sharing-nine-additional-eu-member-states-support-lower-income.

27 “Platform on Sustainable Finance,” European Commission, https://finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/overview-sustainable-finance/platform-sustainable-finance_en.

28 Ichikowitz Foundation, “Africans Have Confidence in China, Survey Shows,” June 22, 2022, https://ichikowitzfoundation.com/news/africans-have-confidence-in-china-survey-shows.

29 James Shikwati, Nashon Adero, and Josephat Juma, “The Clash of Systems, African Perceptions of the European Union and China Engagement,” Friedrich Naumann Foundation, June 2022, https://shop.freiheit.org/#!/Publikation/1278.

30 Vivian Yee, Anton Troianovski, and Abdi Latif Dahir, “Russia Tells Famine-Fearing Africa It’s Not to Blame for Food Shortage,” New York Times, July 24, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/24/world/europe/russia-grain-africa-lavrov.html.

31 Balfour, Bomassi, and Martinelli, “The Southern Mirror.”.

32 Florence Jaumotte, Ksenia Koloskova, and Sweta Saxena, “Migrants Bring Economic Benefits for Advanced Economies,” International Monetary Fund, October 24, 2016, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2016/10/24/migrants-bring-economic-benefits-for-advanced-economies.

33 Paolo Morini, “DEL Dashboard–France,” Development Engagement Lab, June 2023, https://developmentcompass.org/storage/fr-dashboard-june-2023-1687369126.pdf.

34 “Listening to Leaders 2021: A Report Card for Development Partners in an Era of Contested Cooperation,” AidData, June 30, 2021, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/listening-to-leaders-2021.

35 Corentin Cohen, “Will France’s Africa Policy Hold Up?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 2, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/06/02/will-france-s-africa-policy-hold-up-pub-87228; and Folahanmi Aina, “French Mistakes Helped Create Africa’s Coup Belt,” Al Jazeera, August 17, 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/8/17/french-mistakes-helped-create-africas-coup-belt.

36 “Goals & Priority Areas of Agenda 2063,” African Union.

37 Roberto Echandi, Maryla Maliszewska, and Victor Steenbergen, “Making the Most of the African Continental Free Trade Area: Leveraging Trade and Foreign Direct Investment to Boost Growth and Reduce Poverty,” World Bank, June 30, 2022, http://hdl.handle.net/10986/37623.

38 “Debt Sustainability Analysis,” World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/debt-toolkit/dsa.

39 Foulashadé Soulé, “How Popular Are Africa +1 Summits Among the Continent’s Leaders?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, December 6, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/12/06/how-popular-are-africa-1-summits-among-continent-s-leaders-pub-85919.