The burden of environmental degradation is felt not only through physical labor but also emotional and social loss.

Yasmine Zarhloule, Ella Williams

{

"authors": [

"Martha Brill Olcott"

],

"type": "other",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "russia",

"programs": [

"Russia and Eurasia"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Central Asia",

"Turkmenistan"

],

"topics": [

"Climate Change"

]

}

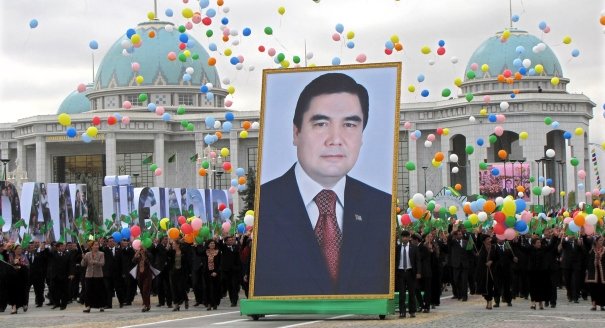

Source: Getty

Turkmenistan has the gas reserves necessary to realize its plan to increase production. However, several geographic and political issues may make it difficult to export Turkmen gas.

Source: James a. Baker III Institute for Public Policy

Turkmenistan has enormous gas reserves, estimated at 13.4 trillion cubic meters (473.2 trillion cubic feet), and is generally ranked fourth globally, behind Russia, Iran, and Qatar. The country’s oil reserves, estimated at 600 million barrels, are substantially smaller. The country has announced plans to increase gas production to 230 billion cubic meters per year (bcm/y), or 8,122 billion cubic feet per year, by 2030—a threefold increase from its previous production high in 1990, and over 3½ times production levels in 2012.

The country obviously has the reserves to justify the optimism of its announced plans, but the natural challenges of exporting gas from this land-locked country and the self-imposed difficulty of doing business in the republic combine to make it far from clear whether Turkmenistan will be able to realize its full potential in the global gas market.This chapter will discuss the development of Turkmenistan’s natural gas sector and the difficulties foreign investors face in attempting to bring Turkmen gas to market. The chapter proceeds in four parts. Part I, “A Brief History,” provides a very brief look at the development of independent Turkmenistan’s political and economic structure. Part II, “The Challenge of Doing Business in Turkmenistan,” describes how Turkmenistan’s business environment has changed under the two presidents that have led the country since independence, the structure of political and economic power, and the pitfalls that foreign investors face. Part III, “Turkmenistan’s Export Challenge,” examines three different primary export scenarios for Turkmen gas—to Russia, Iran, and China—as well as a variety of other planned or previously hoped for export routes that have not come to fruition. Finally, Part IV, “Could a Libyan Scenario Occur in Turkmenistan?” discusses possible sources of social unrest and the potential for drastic political change in the country....

Read the full article on the website of the James A. Baker III institute for Public Policy.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The burden of environmental degradation is felt not only through physical labor but also emotional and social loss.

Yasmine Zarhloule, Ella Williams

For settled descendants of nomadic or seminomadic communities on Jordan’s periphery, the future looks uncertain as government employment is declining, natural resources are dwindling, temperatures are rising, and traditional cross-border ties are restricted.

Armenak Tokmajyan, Laith Qerbaa

For the traditionally nomadic Amazigh pastoralists in the Draa-Tafilalet region, environmental change has exacerbated long-standing inequities, forcing the community to adapt, which has laid bare the blind spots of state-centered climate policy frameworks.

Yasmine Zarhloule, Ella Williams

In an interview, Adam Hanieh looks at heavyweights past and present.

Yezid Sayigh

In fragmented political contexts, climate activism is a way to contest both ecological harm and the structures of violence and neglect that allow it to persist.

Issam Kayssi, Mohanad Hage Ali