Matt Ferchen

{

"authors": [

"Matt Ferchen"

],

"type": "other",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie China"

],

"collections": [

"China and the Developing World",

"China’s Foreign Relations"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie China",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Eastern Europe",

"Western Europe"

],

"topics": [

"Economy"

]

}

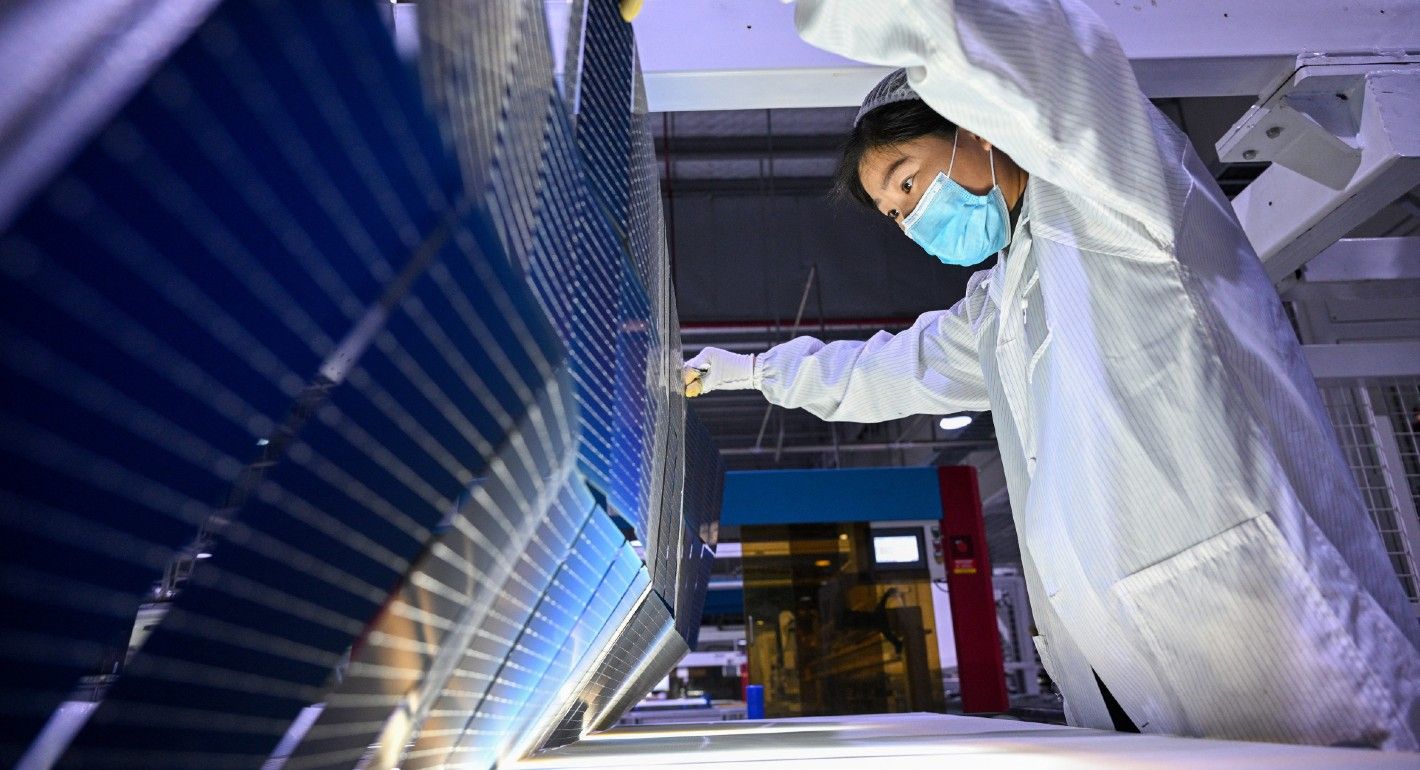

Source: Getty

China, Economic Statecraft and Policy Banks

Concerns about China’s mercantilist trade and investment policies have been at the forefront of growing frictions between China, the EU and the United States, but the Belt and Road Initiative has also highlighted worries about the lending of billions of dollars for infrastructure projects by its “policy banks”.

Source: Clingendael Institute

In a very short amount of time, a new transatlantic consensus about China has emerged: because China is increasingly moving toward illiberalism in its politics and toward mercantilism in its economics, the U.S. and European governments must better understand, and protect themselves from, Chinese strategies to leverage commercial ties for political and geostrategic leverage. Concerns about China’s mercantilist trade and investment policies have been at the forefront of growing frictions between China, the EU and the United States, but the Belt and Road Initiative has also highlighted worries about the lending of billions of dollars for infrastructure projects by its “policy banks”: the China Export-Import Bank and the China Development Bank. However, even though Europe is the desired end-point of the BRI, little has been written about whether China’s policy banks should be considered part of China’s economic statecraft in the region and, if so, what the response should be.

The findings here demonstrate that while China’s policy banks are indeed key instruments of its broader economic statecraft strategies, including within the BRI, they have so far been only peripheral actors in China’s commercial strategies toward the EU. That said, the China Export-Import Bank has been instrumental in financing a signature, if highly controversial, railway project linking the capitals of Hungary and Serbia. In fact, it is in regions like the Western Balkans, with a number of countries that are not (yet) members of the EU, where China’s policy banks have been most active and welcome. Yet as China seeks to gain greater cooperation with EU counterparts to finance and build transportation and energy infrastructure either inside the EU or as part of Eurasian BRI projects, there is every likelihood that its policy banks will be the key instruments for such partnerships. And even if China’s policy banks are currently peripheral to China’s economic statecraft within the EU itself, they are increasingly at the heart of issues such as debt sustainability in regions like the Western Balkans as well in other countries and regions of importance to EU policy. Europe, as well as the United States, therefore has every reason to better understand the role of China’s policy banks in China's broader efforts at economic statecraft around the globe.

About the Author

Former Nonresident Scholar, Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy

Ferchen specializes in China’s political-economic relations with emerging economies. At the Carnegie–Tsinghua Center for Global Policy, he ran a program on China’s economic and political relations with the developing world, including Latin America.

- How China Is Reshaping International DevelopmentQ&A

- Why Unsustainable Chinese Infrastructure Deals Are a Two-Way StreetArticle

Matt Ferchen, Anarkalee Perera

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie China

- How China’s Growth Model Determines Its Climate PerformanceCommentary

Rather than climate ambitions, compatibility with investment and exports is why China supports both green and high-emission technologies.

Mathias Larsen

- What’s New about Involution?Commentary

“Involution” is a new word for an old problem, and without a very different set of policies to rein it in, it is a problem that is likely to persist.

Michael Pettis

- The Chinese Investment Riddle: What Cities RevealCommentary

While China's investment story seems contradictory from the outside, the real answers to Beijing's high-quality growth ambitions are hiding in plain sight across the nation's cities.

Yuhan Zhang

- Using China’s Central Government Balance Sheet to “Clean up” Local Government Debt Is a Bad IdeaCommentary

China's stimulus addiction cannot go on forever. Beijing still has policy space to clean up the country's massive debt issue, but time is running short.

Michael Pettis

- Why China Should Revalue the Renminbi—And Why It Can’t Easily Do SoCommentary

A quick look at the complexities behind Beijing’s enduring Catch-22 situation with revaluing the Renminbi, despite advantages of a stronger currency.

Michael Pettis