Sarah Yerkes

{

"authors": [

"Sarah Yerkes"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [

"Tunisia Monitor"

],

"regions": [

"North Africa",

"Tunisia",

"Maghreb"

],

"topics": []

}

Source: Getty

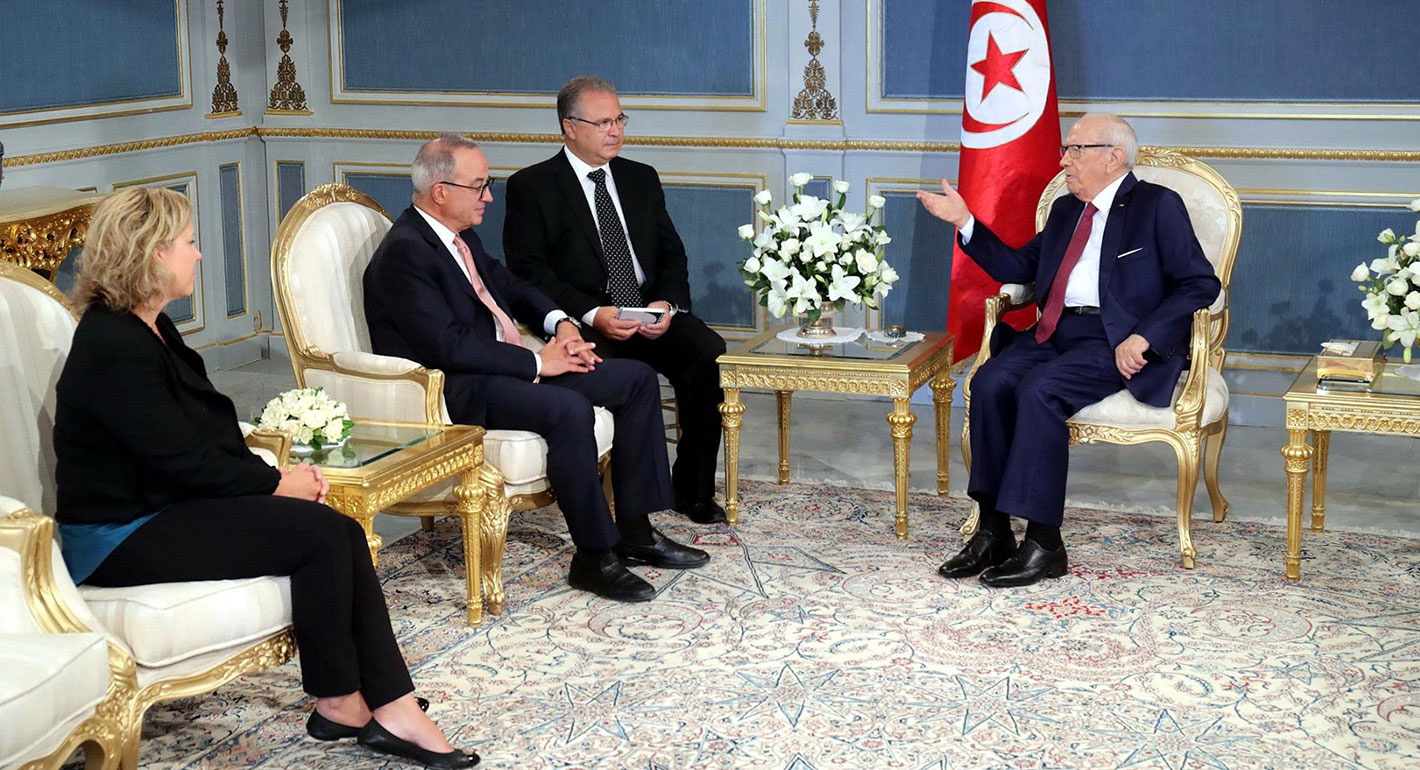

Sarah Yerkes on Beji Caid Essebsi’s Death

Tunisia faces its first transition of power since Beji Caid Essebsi became the first democratically elected president. Carnegie Fellow Sarah Yerkes explains what the recent death of President Essebsi means for the future of Tunisia.

Tunisian President Beji Caid Essebsi passed away on July 25, triggering a new political and institutional challenge for Tunisia.

Essebsi was the country’s first democratically elected president, so Tunisia has never faced this sort of transition.

The turnover has been smooth so far. Following constitutional procedure, speaker of parliament, 85-year-old Mohamed Ennaceur, took over as interim president within hours of the announcement of the president’s death.

But, we could still see some stormy waters ahead.

There are two main issues in short term. First, the constitution requires that new elections be held for president between 45-90 days of his death—at latest, October 23.

But, the country is already scheduled to hold regular presidential elections 3 ½ weeks later—on November 17.

So, the interim president and the electoral body must now decide whether they can pull off early elections and if not, whether they can legally postpone the 90 period to November 17 to keep on the regular schedule.

Ennaceur is also going to need to decide how to handle a new law passed by parliament in June that would exclude certain candidates from running for president in the next election.

President Essebsi had not signed the law before his death, causing anger amongst many parliamentarians.

The interim president does have the power to sign the law, but doing so may be seen as acting against wishes of President Essebsi, who had spoken out against the law.

There are also some longer term implications. First, this is a major blow to Nidaa Tounes, the president’s party. The party is already fractured and operating as two competing branches—one led by his highly unpopular son, Hafedh Caid Essebsi. President Essebsi’s death could spell the end of the party.

Conversely, we are likely to see positive signs for Nidaa’s political rivals—both Ennadha and Tahya Tounes.

For Ennahda, with one of its own in parliamentary speakership today, this could further normalize Islamists in power.

For Tahya Tounes, the party of the prime minister, Youssef Chahed, who had defected from Nidaa, this could give him an opening to take the presidency in November.

All this means Tunisia will be an interesting space to watch over the next few months.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Middle East Program

Sarah Yerkes is a senior fellow in Carnegie’s Middle East Program, where her research focuses on Tunisia’s political, economic, and security developments as well as state-society relations in the Middle East and North Africa.

- Civil Society Restrictions in North Africa: The Impact on Climate-Focused Civil Society OrganizationsArticle

- U.S. Peace Mediation in the Middle East: Lessons for the Gaza Peace PlanPaper

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes, Kathryn Selfe

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie China

- What the Russian War in Ukraine Means for the Middle EastCommentary

It’s about managing oil prices, bread prices, and strategic partnerships.

- +8

Amr Hamzawy, Karim Sadjadpour, Aaron David Miller, …

- A New Foreign Policy Strategy?Commentary

It remains to be seen whether recent foreign policy pivots by the Trump administration amount to a departure from its earlier views about America’s role in the world.

William J. Burns

- Is China A Partner or Predator in Africa (Or Both)?Commentary

China’s relationship with Africa is becoming increasingly more complex as the country continues to invest and send workers across 54 countries on the continent.

Matt Ferchen

- U.S. Allies and Rivals Digest Trump’s VictoryArticle

The world reacts to the election of Donald Trump and its potential implications.

- +9

Thomas Carothers, Lizza Bomassi, Amr Hamzawy, …

- The Sectarianism of the Islamic State: Ideological Roots and Political ContextPaper

The Islamic State’s ideology is multifaceted and cannot be traced to one individual, movement, or period. Understanding it is crucial to defeating the group.

Hassan Hassan