Malaysia’s chairmanship sought to fend off short-term challenges while laying the groundwork for minimizing ASEAN’s longer-term exposure to external stresses.

Elina Noor

{

"authors": [

"Jake Sullivan",

"Kurt M. Campbell"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "americanStatecraft",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "ASP",

"programs": [

"American Statecraft"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States",

"East Asia",

"China"

],

"topics": [

"Foreign Policy"

]

}

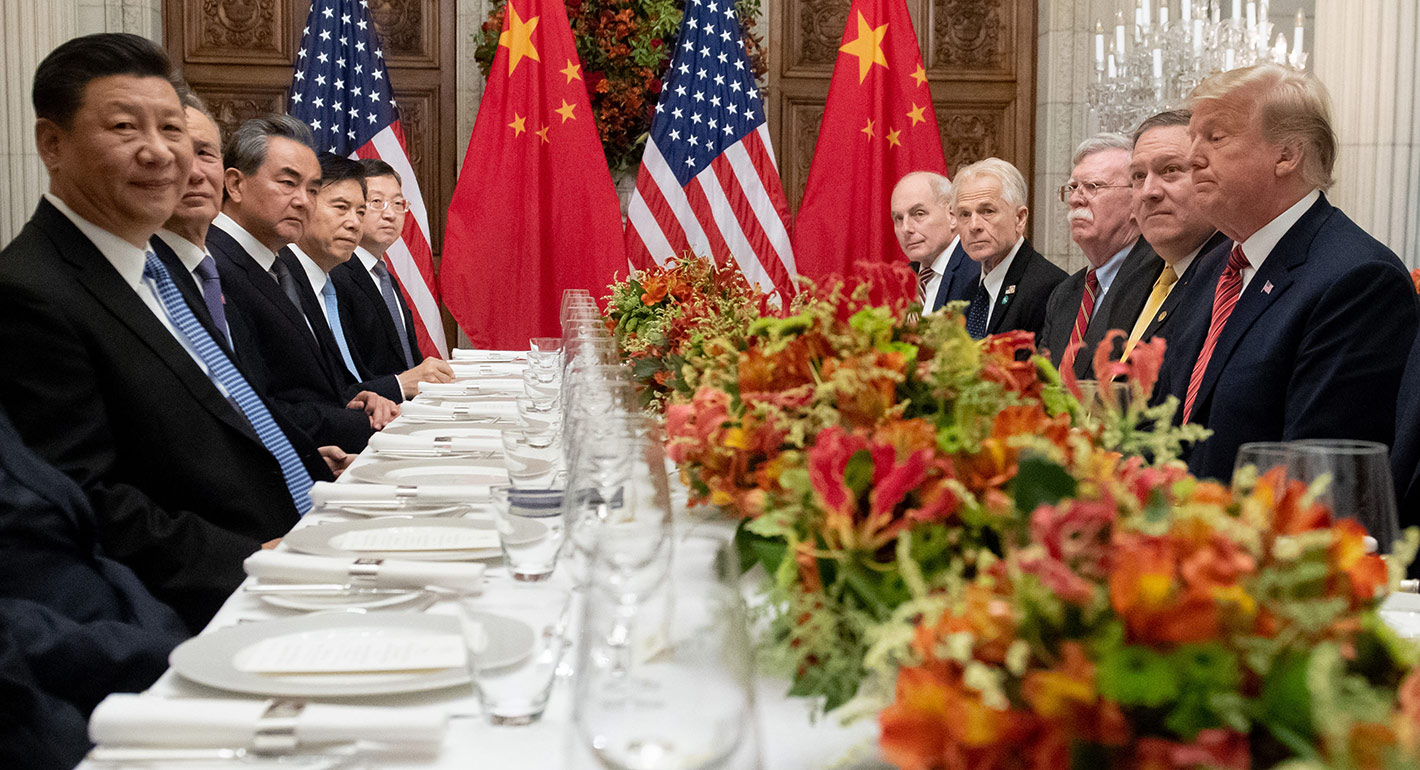

Source: Getty

The United States is in the midst of the most consequential rethinking of its foreign policy since the end of the Cold War. Although Washington remains bitterly divided on most issues, there is a growing consensus that the era of engagement with China has come to an unceremonious close.

Source: Foreign Affairs

The United States is in the midst of the most consequential rethinking of its foreign policy since the end of the Cold War. Although Washington remains bitterly divided on most issues, there is a growing consensus that the era of engagement with China has come to an unceremonious close. The debate now is over what comes next.

Like many debates throughout the history of U.S. foreign policy, this one has elements of both productive innovation and destructive demagoguery. Most observers can agree that, as the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy put it in 2018, “strategic competition” should animate the United States’ approach to Beijing going forward. But foreign policy frameworks beginning with the word “strategic” often raise more questions than they answer. “Strategic patience” reflects uncertainty about what to do and when. “Strategic ambiguity” reflects uncertainty about what to signal. And in this case, “strategic competition” reflects uncertainty about what that competition is over and what it means to win.

The rapid coalescence of a new consensus has left these essential questions about U.S.-Chinese competition unanswered. What, exactly, is the United States competing for? And what might a plausible desired outcome of this competition look like? A failure to connect competitive means to clear ends will allow U.S. policy to drift toward competition for competition’s sake and then fall into a dangerous cycle of confrontation....

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Malaysia’s chairmanship sought to fend off short-term challenges while laying the groundwork for minimizing ASEAN’s longer-term exposure to external stresses.

Elina Noor

For Malaysia, the conjunction that works is “and” not “or” when it comes to the United States and China.

Elina Noor

ASEAN needs to determine how to balance perpetuating the benefits of technology cooperation with China while mitigating the risks of getting caught in the crosshairs of U.S.-China gamesmanship.

Elina Noor

In July 2025, Vietnam and China held their first joint army drill, a modest but symbolic move reflecting Hanoi’s strategic hedging amid U.S.–China rivalry.

Nguyễn Khắc Giang

Regulation, not embargo, allows Beijing to shape how other countries and firms adapt to its terms.

Alvin Camba