Malaysia’s chairmanship sought to fend off short-term challenges while laying the groundwork for minimizing ASEAN’s longer-term exposure to external stresses.

Elina Noor

{

"authors": [

"Paul Haenle",

"Chong Ja Ian"

],

"type": "questionAnswer",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie China"

],

"collections": [

"Carnegie China Commentaries"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie China",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States",

"East Asia",

"China",

"Southeast Asia"

],

"topics": []

}

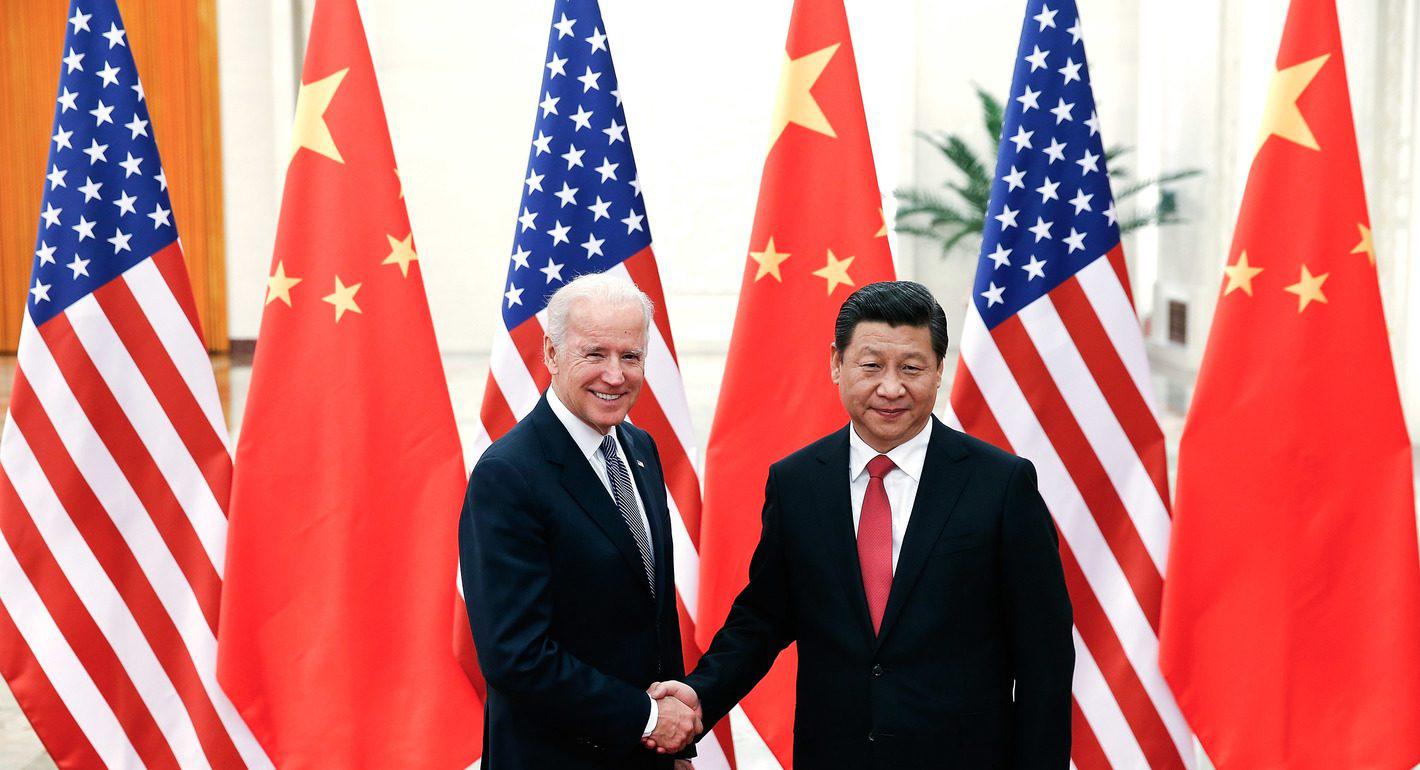

Source: Getty

Southeast Asian capitals would prefer that the U.S. and PRC manage their relationship, if not get along.

On a recent episode of the China in the World podcast, Paul Haenle spoke with Ian Chong, nonresident fellow at Carnegie China, about Southeast Asian views of the Biden-Xi meeting. A portion of their conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, is below.

Paul Haenle: ASEAN countries have a lot at stake in U.S.-China relations. Southeast Asian countries watch very closely the U.S.-China relationship because it is so consequential to them. The Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said recently, “You need a meeting to head in the right direction, but you don’t expect a meeting to make everything sweetness and light.” What, in your view, would ASEAN countries see as a successful meeting between President Xi and Biden? Ian Chong: In ASEAN capitals, the Biden-Xi meeting itself does not necessarily signify anything substantial. If you recall, at last year’s G20 meeting, it appeared that Biden and Xi had a very good conversation. However, the subsequent balloon incident led to an immediate downward spiral in bilateral relations.Southeast Asian capitals would prefer that the U.S. and PRC manage their relationship, if not get along. They will be looking to see if there is real momentum behind the recent economic and political dialogues, and if there will be effort to move forward on military-to-military dialogues. They will also be watching to see how far the PRC side is willing to go in softening its positions on regional security. Before he was removed, General Li Shangfu claimed that there had been an increase in maritime and aerial patrols in and near PRC waters. This, of course, is a matter of dispute. The PRC’s excessive claims put a lot of pressure on Southeast Asian capitals. So they will be watching to see if, as a result of the forward movement in U.S.-China relations, the PRC is willing to dial back its rhetoric and behavior in relation to its excessive regional claims.

To listen to the full episode, use the player below, or subscribe in your favorite podcast app.

Former Maurice R. Greenberg Director’s Chair, Carnegie China

Paul Haenle held the Maurice R. Greenberg Director’s Chair at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and is a visiting senior research fellow at the East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore. He served as the White House China director on the National Security Council staffs of former presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama.

Nonresident Scholar, Carnegie China

Chong Ja Ian examines U.S.-China dynamics in Southeast Asia and the broader Asia-Pacific.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Malaysia’s chairmanship sought to fend off short-term challenges while laying the groundwork for minimizing ASEAN’s longer-term exposure to external stresses.

Elina Noor

For Malaysia, the conjunction that works is “and” not “or” when it comes to the United States and China.

Elina Noor

ASEAN needs to determine how to balance perpetuating the benefits of technology cooperation with China while mitigating the risks of getting caught in the crosshairs of U.S.-China gamesmanship.

Elina Noor

In July 2025, Vietnam and China held their first joint army drill, a modest but symbolic move reflecting Hanoi’s strategic hedging amid U.S.–China rivalry.

Nguyễn Khắc Giang

Regulation, not embargo, allows Beijing to shape how other countries and firms adapt to its terms.

Alvin Camba