Source: Carnegie

Prepared

testimony by

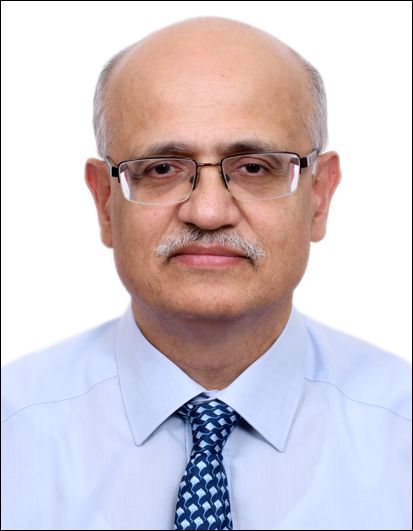

Leonard S. Spector, Senior Associate Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

before the

House International Relations Committee September 12, 1996

Mr. Chairman, it is an honor to testify before the Committee this morning to

examine China's role in assisting Iran's programs to develop weapons of mass

destruction and missiles for delivering them.

As the committee is aware, assessing this situation is particularly difficult

because of the secrecy surrounding both Iran's sensitive weapons programs and

China's export activities. Nonetheless, a preliminary evaluation can be made

on the basis of the published statements of U.S. officials and credible press

accounts.

Nuclear Weapons

Although Iran is prohibited from developing nuclear weapons by virtue of its

status as a non-nuclear-weapon state party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation

Treaty (NPT), Iran is widely believed to be pursuing the development of nuclear

arms. In the view of the U.S. intelligence community, Iran's program remains

in its early stages and is eight to ten years from fruition, although this timetable

could be accelerated depending on the extent of outside support Iran receives.

The most difficult aspect of developing nuclear arms is producing nuclear weapons

material. Iran appears to be pursuing two routes to nuclear arms: (1) acquiring

weapons-usable nuclear material —or even complete weapons themselves—from

the former Soviet Union and (2) developing a domestic production capability,

with the greatest emphasis apparently on the use of gas centrifuges to enrich

uranium to weapons-grade. So far Iran is not known to have made significant

progress along either track, and, for example, it is not thought to have under

construction any of the most sensitive installations that would be needed for

the production of weapons-grade uranium or plutonium.

As a member of the NPT, Iran has agreed to subject all of its nuclear activities

to monitoring by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), an organization

whose powers now include the right to demand inspection of suspected, undeclared

nuclear facilities. To avoid the implication of wrong-doing that the demand

for such special inspections might carry, Iran has voluntarily agreed to permit

the IAEA to visit any site in the country. To date the agency has made two visits

under this arrangement, neither of which disclosed improper activities.

Although this has not allayed U.S. concerns, the availability of intrusive

IAEA monitoring serves as a highly valuable tool for helping to check Iranian

nuclear advances.

According to the Pentagon, China is a "principal supplier of nuclear technology

to Iran," but the precise extent of China's contribution to Iran's nuclear

program is unclear.

China has supplied several small research reactors to Iran, which would be

useful in training Iranian nuclear specialists, but which are too small to help

in producing weapons-grade materials.

China also appears to have provided Iran extensive assistance in developing

its uranium resources, including aid in the design of a plant for producing

uranium hexafluoride. This facility, which appears ill-suited to Iran's civilian

nuclear power program, could, when completed, provide raw material that could

eventually be improved, in gas centrifuges, into bomb-grade uranium. The installation

would be subject to IAEA inspection, however, severely limiting Iran's ability

to divert any uranium hexafluoride to weapons without detection. On the other

hand, unprocessed uranium concentrate is not monitored by the agency, creating

opportunities for Iran to attempt to siphon the material off for a secret, parallel

nuclear weapons effort; and, once Iran had learned to produce uranium hexafluoride

in an inspected facility, it might be tempted to build a secret one.

In late 1995, China suspended plans, announced in 1992, to supply Iran with

two nuclear power plants, in part because of U.S. efforts to discourage the

sale. The United States has led an international nuclear embargo of Iran, which

all Western suppliers have supported. This effort apparently led France, Germany,

and Japan to decline to supply components to China that it needed for the reactors

it had offered Iran, contributing to the suspension of the deal.

China is a nuclear-weapon-state party to the NPT. Although this status allows

it to retain its own nuclear arsenal, the treaty prohibits it from assisting

any other state to develop nuclear weapons. In addition, the treaty requires

that all nuclear exports from China be placed under IAEA inspection in the recipient

state, a rule China has apparently followed so far with Iran, judging from the

information that is publicly available. Following a controversy with the United

States over the sale of nuclear equipment to Pakistan, moreover, Beijing pledged

in May 1996 that it would not provide assistance to any nuclear facility not

subject to IAEA inspection—an understanding that would appear to rule out

assistance to any facility that Iran might try to hide from the IAEA.

These restrictions may help limit improper Chinese assistance to Iran's nuclear

weapons program in the future.

Recently, in a written submission to the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence,

the CIA affirmed this view, stating that China's commitment to various arms

control regimes, including the NPT, had "led to a moderate decline in its

sensitive exports to other countries."

Chemical and Biological Weapons (CW and BW)

According to recent information provided by the CIA to the Senate Intelligence

Committee:

Iran's CW program is already among the largest in the Third World, yet it has

continued to expand and become more diversified, even since Tehran's signing

of the CWC [Chemical Weapons Convention] in January 1993. Iran's stockpile is

comprised of several thousand tons of CW agents, including sulfur mustard, phosgene,

and cyanide agents, and Tehran is capable of producing an additional 1,000 tons

of these agents each year. In addition, Iran is developing a production capability

for the more toxic nerve agents and is pushing to reduce its dependence on imported

raw materials. Iran has various dissemination means for these agents, including

artillery mortars, rockets, aerial bombs, and, possibly, even Scud warheads.

As for Iran's BW capabilities, the CIA reported:

Iran has had a biological-warfare program since the early 1980s. Currently,

the program is mostly in the research and development stages, but we believe

Iran holds some stocks of BW agents and weapons. For dissemination, Iran could

use any of the same delivery systems—such as artillery and aerial bombs—that

it has in its CW inventory. We are concerned that in the future Iran may develop

a biological warhead for its ballistic missiles, but we would not expect this

to occur before the end of the century.

As is true in the case of Iran's nuclear program, China's role in facilitating

Iran's CW and BW programs is also uncertain. Chinese firms have apparently played

a role in supplying CW precursors to Iran, leading to the imposition of sanctions

against several firms and persons in 1994 and 1995. In November 1995, referring

to Iran's CW program, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Near East and

South Asia Bruce Reidel testified:

In the chemical arena, we have seen some evidence that China has provided some

assistance or Chinese firms have provided some assistance, both in terms of

the infrastructure for building chemical plants and some precursors for developing

agents. I would point out here that the Chinese chemical industry is very rapidly

growing at this time, and not all facets of it may be under the fullest scrutiny

of the Chinese government.

U.S. officials have not indicated whether China is implicated in Iran's BW

program.

Iranian ratification of the Chemical Weapons Convention would dramatically

alter the threat posed by its CW capabilities, since Tehran would be required

to destroy its existing stocks and place all relevant facilities under international

monitoring. China's ratification of the CWC, it may be added, would require

it not only to destroy any CW stocks it might have, but also to implement effective

national export controls on CW precursors.

Iran's acquisition of BW stocks is a violation of the Biological Weapons Convention

(BWC), to which it is a party. Unlike the NPT (and the pending Chemical Weapons

Convention), the BWC does not include verification mechanisms that could provide

clear evidence of such violations. The BWC, however, does permit parties to

call on the UN Security Council to investigate alleged violations, which could

set the stage, in turn, for UN action against states infringing the pact. Unfortunately,

this mechanism has never been invoked.

In sum, at the present time, the threat posed by the Iranian CW/BW program

is far more immediate than that posed by the country's nuclear activities. However,

Chinese involvement may be less significant.

Missile Programs

Other witnesses will be examining in some detail Iran's missile capabilities

and their military implications.

Let me concentrate, instead, on China's role in this sphere and the applicability

of U.S. sanctions law. Broadly speaking, the components of the Iranian missile

threat of greatest concern to the United States and its friends are Iran's:

- 300-km Scud-B missiles, supplied by North Korea;

- 500-km Scud-C missiles, supplied by North Korea;

- Scud production capabilities, which apparently incorporate Chinese equipment

and/or technology;

- 150-km CSS-8 missiles, supplied by China; and

- various anti-ship cruise missiles, some purchased from China and others

being developed by Iran with Chinese assistance.

In 1995, China was also reported to have transferred "dozens, perhaps

hundreds, of missile guidance systems and computerized machine tools" to

Iran. In addition, a recent press report indicates that Iran may be developing

a new 1,500-km missile, the "Zelzal-3," based on technology from China,

Russia, North Korea, and Germany.

China pledged to the United States in February 1992 that it would abide by

the standards and parameters of the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR)

and pledged in October 1994 that it would not transfer surface-to-surface missiles

inherently capable of carrying a 500 kg payload to a distance of 300 km or more.

Apparently Beijing interprets these undertakings as permitting transfers of

missile-production technology and missile components, however.

Without going into all of the intricacies of U.S. sanctions laws, it would

appear that, if it were continuing today, China's transfer of any type of missile

production technology or of missile components (such as guidance

systems) to Iran, would violate the basic U.S. sanctions law regarding missile

transfers. Secondly, Chinese transfers of the shorter-range CSS-8 would probably

not violate that law. Finally, Chinese transfers of cruise missiles might violate

the Iran-Iraq Non-Proliferation Act, if deemed to be in "destabilizing

numbers and types."

Next Steps for the United States

The Clinton Administration is pursuing a multi-faceted strategy to constrain

China's assistance to Iran's WMD and missile programs —and to reduce the

dangers posed by those programs, themselves.

Diplomatic activism. First, it has used assertive diplomacy, including

jaw-boning, the threat of sanctions under existing U.S. laws, and the imposition

of such sanctions to pressure China to reduce its support for Iran's most sensitive

weapons programs. On the plus side, we have seen China suspend its planned sale

of two nuclear power plants to Iran, and we have also seen China refrain from

selling its advanced M-9 missile in the region, as was feared in the late 1980s.

It is possible that Chinese assistance to Iran's CW program has also been curtailed

as the result of U.S. diplomatic activism. On the negative side, however, it

must be recognized that China may be in the process of assisting Iran to build

a uranium hexafluoride plant, a facility of some relevance to a nuclear weapons

program; that Chinese missile production-technology and missile-component transfers

may be continuing; and that Chinese sales of shorter-range ballistic and strategically

important anti-ship cruise missiles may be continuing. The record here may be

as good as one might realistically hope for, but it is clearly imperfect, nonetheless.

Regime-building and enforcement. The Administration is also working

in a second area, by attempting to strengthen relevant non-proliferation regimes.

The indefinite extension of the NPT in May 1995 and the enhanced authority of

the IAEA (including its right to conduct special inspections of suspected undeclared

nuclear sites, which has led to Iran's voluntary offer of unrestricted IAEA

visits) create significant impediments to Iran's nuclear weapons effort; they

also place significant restraints on Chinese nuclear exports. If the Chemical

Weapons Convention enters into force, pressures will mount on Iran to ratify

the pact—a step that could, in turn, lead to the elimination of its CW

program and to tight, on-going inspections. Even if Tehran remains outside the

treaty, the pact will impose new restrictions on all other parties prohibiting

transfers to it of sensitive dual-use chemicals. The broad acceptance of the

prohibition against chemical armaments embodied in the treaty would, moreover,

increasingly isolate Iran as a malefactor. U.S. ratification of the treaty is

essential to its success.

In the more difficult area of biological weapons, a demand for a UN Security

Council investigation of U.S. charges that Iran possesses biological weapons

might be a further useful step toward strengthening international non-proliferation

controls.

Intelligence. A third, critically important element of the U.S. effort

to address the China-Iran WMD connection and to restrain Iranian WMD ambitions

is the aggressive use of intelligence resources. In many respects, this is the

sine qua non for all other U.S. initiatives. It has given Washington

the ability to ferret out Tehran's clandestine activities; to intervene on numerous

occasions to block sales to Iran of sensitive technology and equipment, including

those from China; to provides strategic warning of Iranian intentions; and to

enable the United States to help the IAEA develop targets for its special visits

in Iran —a role U.S. intelligence would be able to play in the CW area

if Iran accepts the CWC.

Counterproliferation. Fourth, with the active support of Congress, the

Administration has developed the Defense Counterproliferation Initiative. The

initiative seeks to apply U.S. military resources to address proliferation,

particularly in the CW/BW and missile areas, if preventive measures fail. The

effort includes the development of passive defenses, active defenses, new operational

approaches, and other related measures.

Enhanced controls in the former Soviet Union. The single most important

measure needed to contain Iran's WMD programs, however, does not involve China,

but rather Russia and the other Soviet successor states. Loss of control here

over nuclear weapons, weapons-usable nuclear material, chemical weapons, biological

weapons, and related production technology could drastically alter global proliferation

patterns—and Iranian capabilities, in particular—overnight. Administration

programs to assist Russian denuclearization efforts, to provide non-military

employment opportunities for key Soviet scientists, and to enhance protection

of materials usable for nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons is critically

important. Fortunately, this area, too, has enjoyed broad bipartisan support

in Congress.

***

Mr. Chairman, there are no easy answers for addressing the dangers posed to

our friends and our interests by the Iranian proliferation threat—or for

eliminating China's contribution to the problem. The multi-pronged U.S. approach

to this challenge has had some successes and may enjoy more. Continued bipartisan,

Congressional-Executive Branch collaboration is essential for us to make further

progress.

[Top of the Page]