When Growth Models Create Climate Contradictions

In terms of climate performance, China is simultaneously the world’s cleanest and dirtiest economy. The country’s record-breaking development of green industries and equally record-breaking greenhouse gas emissions are well known. While this may sound logically incoherent, it is not. It is a natural outcome of China’s growth model. Simply put, both the cleanest and most carbon-intensive industries fit the country’s economic structure. For example, both solar panels and metal products are used for exports as well as domestic investment. They are, therefore, heavily subsidized and supported by the state. Consequently, scaling up clean industries is as natural a part of China’s growth model as the inability to scale down carbon-intensive industries.

Running in Parallel: China’s Green-Industrial Revolution

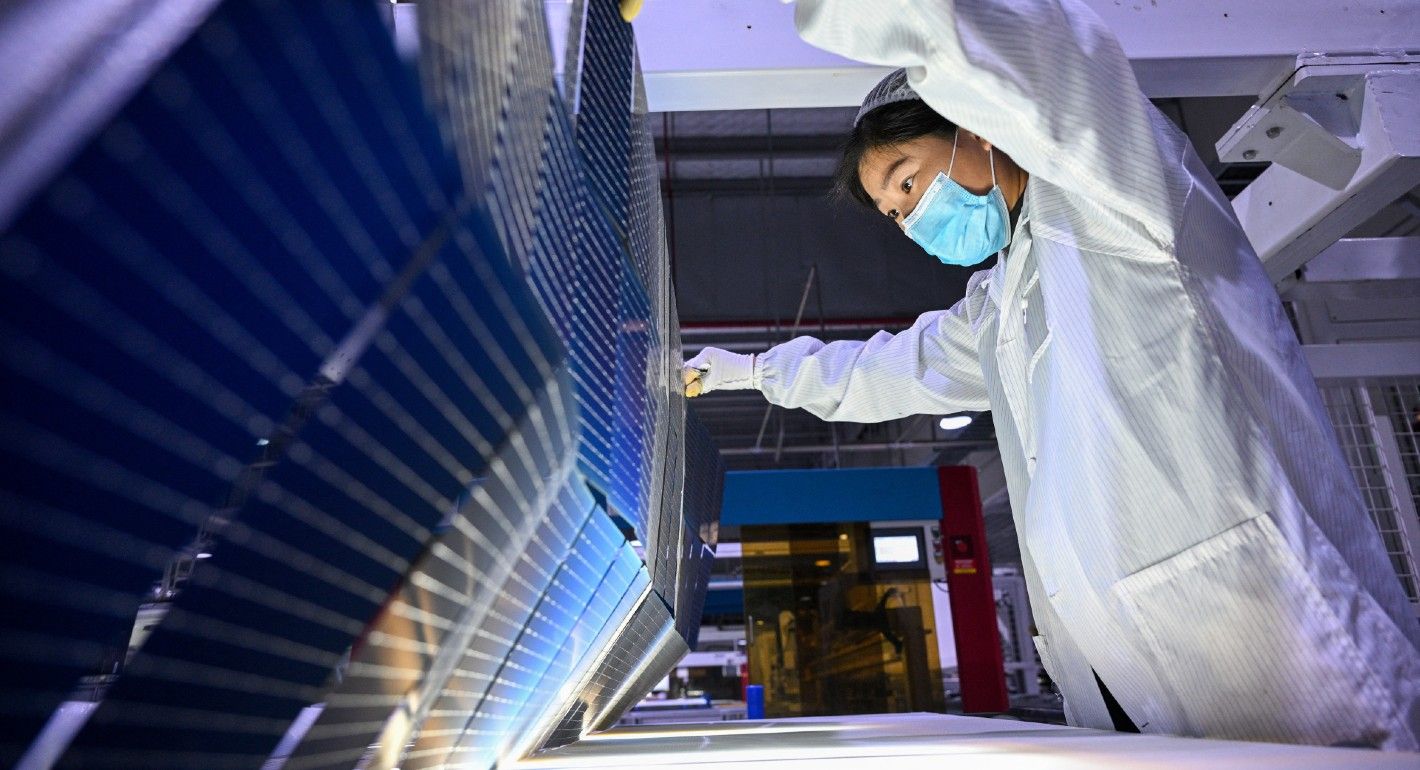

Consider each side in turn: The clean side includes solar, wind, batteries, electric vehicles, and electric rail transport. The fit between these industries and the growth model can be seen across several interrelated dimensions: First, clean technologies are part of high-tech upgrading of the economy by moving up value chains, which can increase overall productivity and spark growth. Indeed, as a fight against “Japanification” of its economy, China has made huge investments in clean technologies with the goal of boosting long-term growth.

Second, renewables can generate massive investments in manufacturing and installation, which is critical for local governments looking for investment opportunities and construction companies looking for project opportunities, both to compensate for the real-estate slump. For example, in addition to renewables themselves, China has plans to spend $800bn on the electricity grid, which, in itself, creates growth. Here, the higher up-front costs of renewables compared to fossil fuels might even be an advantage, as it shows up as higher growth. Third, clean industries fit with China’s international security needs. This is both in terms of reducing the need to import oil for combustion engine cars and reducing dependence on other countries for importing these green goods. In these ways, green industries provide new growth sectors within the same growth model.

On the dirty side, certain emission-intensive industries similarly fit China’s growth model and therefore receive state support. First, they support exports, such as seen with China’s increasing exports of steel. Second, they can also be part of moving towards higher technology and more value-adding parts of supply chains. For example, China is massively increasing capacity in its petrochemical industry, with the majority of investments coming from state-owned enterprises. Third, while intending to reduce dependence on importing fossil fuels, coal is abundant in China, meaning that the continued scale-up of coal capacity for power generation supports domestic GDP and the needs for international security. Given China’s growth model’s reliance on these economic activities, it is not possible to scale them down without either switching to another growth model or making the short-term economic sacrifice in shifting to more expensive green technologies in such industries. For example, powering steel production with renewables and green hydrogen is far more costly than with coal.

That China supports both the cleanest and most emission-intensive industries is seen in export data. In fact, in terms of exports, heavy industries remain a far larger component of Chinese exports than clean industries. While the ‘new three’ clean exports amount to $143bn, high-emission exports, such as metals, amount to $296bn, with chemicals at $213bn, plastic & rubbers at $189bn, and mineral products at $75bn. Highlighting this contrast, these numbers add up to $143bn in clean exports and $773bn in emission-intensive exports. Emphasizing the role of these green technologies in exports, Xi Jinping expresses the intention that the ‘new three’ replace the ‘old three’ of clothing, furniture, and home appliances. These new three grew from 1.5% of exports in 2020 to 4.5% in 2023. Although Beijing appears happy to add new technologies as drivers of exports, it shows no intention of scaling down emission-intensive industries.

China’s Growth and Climate Dilemma: Add Clean, Keep Dirty?

Ultimately, China’s growth model embraces the scaling up of clean industries just as readily as it resists scaling down carbon-heavy ones – the answer to what might seem like a paradoxical climate performance is, thereby, that both types of industries flourish under China’s growth model. In extension, this explanation leaves no room for the argument that the Chinese government is seriously concerned about climate change. Indeed, according to Climate Action Tracker, China’s climate performance and ambitions are ‘highly insufficient.’ Reflecting this, in spite of the impressive rollout of renewables, China is responsible for 93% of global additional emissions since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015. China’s problematic climate performance suggests an unwillingness to compromise on its growth model for the sake of addressing the climate crisis - while there are no climate deniers in Beijing, there are, indeed, climate neglecters.