Source: Carnegie

by Jon Wolfsthal, Associate

Reprinted with permission from Moscow Times, February

5, 2002

President George W. Bush's State of the Union remarks labeling

Iran, Iraq and North Korea as an axis of evil quickly circled the globe and

reignited fears of a more aggressive brand of U.S. unilateralism. No one in

the United States, especially in the wake of Sept. 11, should be shy about openly

defending U.S. security, but the administration has a responsibility to do more

than, as they say, "put states on notice." True leadership means being a catalyst

for changing behavior that threatens U.S. interests. In all three cases, the

United States has many options other than military force or public condemnation

at its disposal. Many of these other steps would benefit from recapturing the

traditional U.S.-Russian shared interest in stemming the spread of weapons of

mass destruction.

The most promising, but delicate case is North Korea, where

negotiations under former U.S. President Bill Clinton's administration succeeded

in heading off North Korea's production of a sizable and uncontrolled nuclear

arsenal, suitable for use or export. The U.S.-North Korean Agreed Framework

of 1994 froze Pyongyang's nuclear program in its tracks and showed that North

Korea can be reasonable and is willing to end programs that threaten U.S. interests

if appropriately motivated. The Bush administration has offered to resume contacts

with North Korea, but its public comments and condemnations have signaled to

Pyongyang that talks are not likely to be a pleasant experience, filled with

more lectures than constructive proposals.

If it is serious about modifying North Korean behavior,

the Bush administration needs to engage in a positive dialogue with Pyongyang

and take steps to support efforts by South Korea to resume a peaceful dialogue

with the North. President Vladimir Putin helped frame the outlines of a negotiated

ban on missile development and exports before Bush took office and, if the Bush

administration feels it cannot send an emissary of its own to Pyongyang, Russia

should be considered as an intermediary to resume a productive dialogue.

In Iran and Iraq, two states with ongoing proliferation

programs, the United States has several tough, but potentially productive options.

In Iraq, a serious attempt to reinstate an inspection regime backed by military

assets to protect inspectors, is a more attractive alternative to the forceful

removal of Saddam Hussein. While Saddam's continued rule in Iraq makes each

day an adventure, unless the United States has the clear mandate and support

of its allies in the region and elsewhere (especially Moscow and in Europe),

occupying Iraq and rebuilding that country in the U.S. image threatens to be

more than even Washington can handle without a major commitment of time, energy,

money and lives. Baghdad is not Kabul and the Republican Guard is not the Taliban.

Russia has been, and continues to be, the key to an improved inspections and

sanctions regime. By taking the lead in reinstituting inspections, Moscow could

do much to improve its non-proliferation standing in Washington and pave the

way for the adoption of smart sanctions against Iraq that would improve the

flow of Iraqi payments to Moscow. In return, Washington should reassure Moscow

that steps will be taken to ensure that Iraqi debts to Moscow are honored.

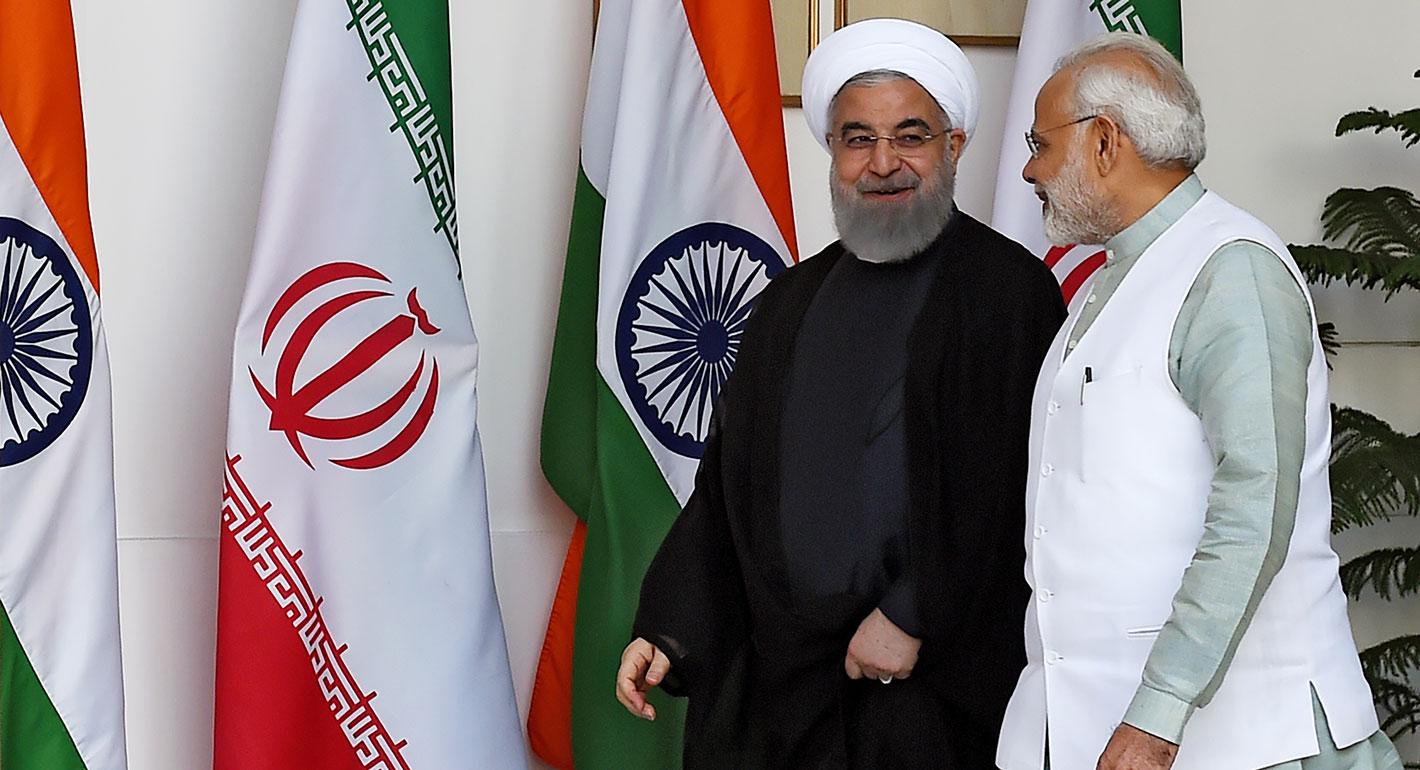

Iran is the definition of a Catch-22, where the United States

is damned if it tries to support the reformers, and damned if it does not. Any

praise of the elected regime only weakens those rulers in their battle against

the oppressive religious clerics, but still more needs to be done if the future

is to bring about true reform in Iran before its programs to develop long-range

missiles and a nuclear option bear fruit. Here, the true value of the U.S.-Russian

relationship can shine through. Repeating old arguments about Iran's nuclear

program will do nothing to improve U.S.-Russian relations, but facts are facts.

Iran has publicly declared its desire to acquire nuclear weapons. Iran's acquisition

of nuclear weapons and long-range missiles threatens both Moscow's and Washington's

interests, regardless of its source. This, in itself, should be enough to give

Moscow pause in helping Iran's civilian nuclear program. Moscow's refusal to

acknowledge this fact is as stubborn as Washington's misplaced opposition to

Tehran's acquisition of advanced conventional weapons from Moscow, for which

Russia will receive more money than it will from the completion of the Bushehr

reactor. Working constructively, Bush and Putin should be able to cooperatively

constrain Iran's access to nuclear technology while easing controls on less

destabilizing conventional weaponry.

None of these steps will be easy, and none are as attractive

to a domestic U.S. audience as "rogue state" bashing. Grandstanding against

"rogue regimes" is good politics in the United States after Sept. 11, but does

little to make the country more secure, and weakens prospects for working with

U.S. allies on real solutions to these serious proliferation problems. By working

with Russia, the United States can accomplish a lot more than it can by working

alone. In the process, the Bush administration can go a long way toward making

the promise of the new partnership with Moscow a reality.