- +18

James M. Acton, Saskia Brechenmacher, Cecily Brewer, …

{

"authors": [

"Tong Zhao"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie China"

],

"collections": [

"The Day After: Navigating a Post-Pandemic World",

"Carnegie China Commentaries"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie China",

"programAffiliation": "NPP",

"programs": [

"Nuclear Policy"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

Source: Getty

View From Beijing

Effective nuclear arms control engagement with China will likely require confidence-building measures by the United States and greater support from the international community.

All major powers must recognize that, despite their strategic competition, they have a common interest in pursuing arms control to manage that competition and minimize the risk of military conflicts. Thus, the United States should be able to engage China on arms control if it sets the right goals. But if Washington continues to present arms control as a tool to compete with Beijing, why would Beijing help?

If Washington continues to present arms control as a tool to compete with Beijing, why would Beijing help?

Washington cannot coerce Beijing by threatening to start an arms race and spend China “into oblivion,” especially because Beijing is confident it can outcompete Washington in the long run. Such a threat also reinforces China’s long-standing suspicion that arms control is a concession imposed by the strong and accepted by the weak.

The United States will have to keep its public voice down while offering China concrete proposals to address the two countries’ asymmetric capabilities. If they’re to be taken seriously, these proposals should show a willingness by the United States to limit its own capabilities, particularly in areas of U.S. superiority such as air- and sea-launched missile systems and space-based capabilities.

Appeals to the United States and China by the international community for responsible behavior would also have an impact. As U.S.-China competition intensifies, both countries understand the need to win support from third parties.

Given China’s deep skepticism and outsider status in the arms control arena, engagement will require transparency and time to build confidence. One valuable starting point could be a reset of fundamental terms: China may be more eager to discuss “strategic ability” than “arms control.” Identifying cooperative measures for nuclear risk reduction would be a useful topic for initial discussions.

To proceed with substantive talks, Beijing would need reassurance that Washington accepts a relationship of mutual vulnerability and does not seek to challenge its strategic nuclear deterrence. China’s concern over U.S. missile defense, if left unaddressed, would remain the strongest external driver of its comprehensive nuclear modernization. Perhaps the two parties could agree to a joint study on the technical feasibility of making the U.S. system capable only of defending against North Korean strategic missiles without undermining China’s nuclear retaliation capacity.

In China’s highly centralized political system . . . the blessing of top political leadership is key.

In China’s highly centralized political system, in which arms control experts are scattered and do not have a strong voice, the blessing of top political leadership is key to generating momentum for arms control talks. World leaders should engage with President Xi Jinping directly: his support, even a merely symbolic endorsement of the concept of arms control, would help start a much-needed domestic discussion.

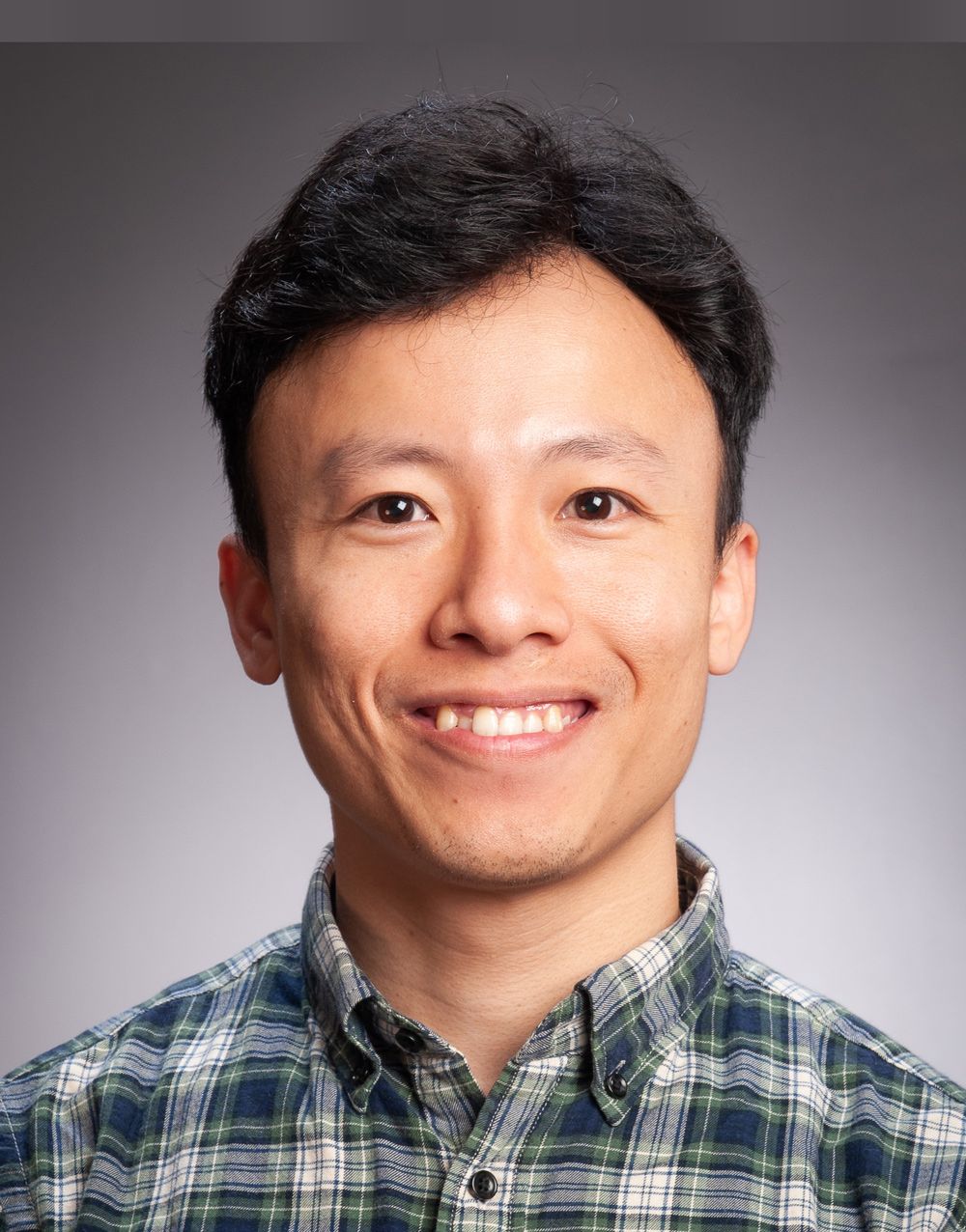

About the Author

Senior Fellow with the Nuclear Policy Program and Carnegie China

Tong Zhao is a senior fellow with the Nuclear Policy Program and Carnegie China, Carnegie’s East Asia-based research center on contemporary China. Formerly based in Beijing, he now conducts research in Washington on strategic security issues.

- Unpacking Trump’s National Security StrategyOther

- The U.S. Venezuela Operation Will Harden China’s Security CalculationCommentary

Tong Zhao

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie China

- Malaysia’s Year as ASEAN Chair: Managing DisorderCommentary

Malaysia’s chairmanship sought to fend off short-term challenges while laying the groundwork for minimizing ASEAN’s longer-term exposure to external stresses.

Elina Noor

- When It Comes to Superpower Geopolitics, Malaysia Is Staunchly NonpartisanCommentary

For Malaysia, the conjunction that works is “and” not “or” when it comes to the United States and China.

Elina Noor

- ASEAN-China Digital Cooperation: Deeper but Clear-Eyed EngagementCommentary

ASEAN needs to determine how to balance perpetuating the benefits of technology cooperation with China while mitigating the risks of getting caught in the crosshairs of U.S.-China gamesmanship.

Elina Noor

- Neither Comrade nor Ally: Decoding Vietnam’s First Army Drill with ChinaCommentary

In July 2025, Vietnam and China held their first joint army drill, a modest but symbolic move reflecting Hanoi’s strategic hedging amid U.S.–China rivalry.

Nguyễn Khắc Giang

- Today’s Rare Earths Conflict Echoes the 1973 Oil Crisis — But It’s Not the SameCommentary

Regulation, not embargo, allows Beijing to shape how other countries and firms adapt to its terms.

Alvin Camba