Source: Financial Times

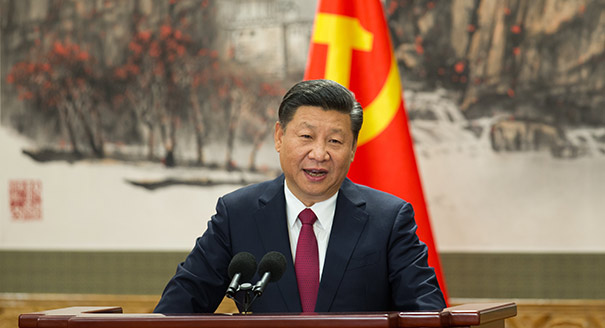

China’s 19th Communist party congress ended last month with an indication that Xi Jinping’s new administration plans to rein in debt by abandoning the country’s long-term economic targets and allowing gross domestic product growth to fall.

Typically, analysts assume that changes in reported GDP reflect movements in living standards and productive capacity. In China, however, this is not the case. Local governments are expected to boost spending by whatever amount is needed to meet the country’s targets, whether or not it is productive.

GDP growth is not the same as economic growth. Consider two factories that cost the same to build and operate. If the first factory produces useful goods, and the second produces unwanted ones that pile up as inventory, only the first boosts the underlying economy. Both factories, however, will increase GDP in exactly the same way.

Most economies, however, have two mechanisms that force GDP data to conform to underlying economic performance. First, hard budget constraints, which set spending limits, drive companies that systematically waste investment out of business before they can substantially distort the economy.

Second, there is a market-pricing factor in GDP accounting that when bad debts caused by wasted investment are written down, the value-added component of GDP and the overall level of reported growth are reduced.

In China, however, neither mechanism works. Bad debt is not written down and the government is not subject to hard budget constraints. It is the government sector that is mainly responsible for the investment misallocation that characterises so much recent Chinese growth.

The implications are obvious, even if most economists have been surprisingly reluctant to acknowledge them. Anyone who believes there has been a significant amount of wasted investment in China must accept that reported GDP growth overstates the real increase in wealth by the failure to recognise the associated bad debt. Were it correctly written down, by some estimates GDP growth would fall below 3 per cent.

Historical precedents suggest the potential magnitude of this overstatement. Japan’s economy in the 1980s, for example, had distortions that resemble those of China today. Although not nearly as extreme, Japan too suffered from a very low consumption share of GDP and an overreliance on investment that, by the 1980s, had veered into substantial misallocation.

In the early 1990s, Japan’s reported GDP comprised 17 per cent of the overall global total, and few doubted that its soaring economy would become the world’s largest by the end of the century. Instead, once credit growth stabilised, Japan’s share of global GDP began to plummet, and has since fallen by nearly 60 per cent.

The same happened to the former USSR. It grew so quickly after the second world war that by the late-1960s it comprised 14 per cent of global GDP, similar to China today, and was widely expected to overtake the US. But two decades later, its share of global GDP had fallen by more than 70 per cent.

These cases may appear shocking, but, like China today, 1980s Japan and 1960s Russia lacked the mechanisms to account for wasted investment in reported GDP. At their peaks, growth for each country was seriously overstated by the failure to write down the waste, and understated once debt levels stabilised.

The implications are clear. China’s growth miracle has already run out of steam. It is only by allowing debt to surge that the country is able to meet its GDP targets. This may be why President Xi has been eager to stress more meaningful goals, such as increasing household income. Whatever the reason, analysts should not read GDP growth as an indicator of China’s underlying economic performance. Piling up unsold and unsaleable goods or building empty airports may boost GDP in an economy whose financial system does not recognise bad debt, but it does not measure its performance.

This article was originally published in the Financial Times.