This publication is a product of Carnegie China. For more work by Carnegie China, click here.

Technology is the major engine propelling the global economy, but it is also at the heart of geopolitical competition between the United States and China. For ASEAN, its deepening linkages with China on technology will be tested in the face of geopolitical pressures, supply chain fragmentation, and asymmetric power dynamics.

In short, ASEAN needs to determine how to balance perpetuating the benefits of technology cooperation with China while mitigating the risks of getting caught in the crosshairs of U.S.-China gamesmanship.

Supply and Demand Complementarity

There has long been complementarity between ASEAN and China when it comes to the digital economy. With young, mobile-first populations in countries like the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam, ASEAN’s digital economy surpassed $200 billion in 2024 and is projected to exceed $300 billion in 2025. Meanwhile, China has become a technology leader that can offer—and meet ASEAN’s growing demand for—services across the tech stack from products, platforms, capital, and infrastructure.

As such, China’s tech companies have long been bullish on ASEAN’s large market and growth potential. Alibaba, Tencent, Huawei, and Ant Group are already well-entrenched in Southeast Asia’s digital landscape. Huawei, for example, has been present in the region for over twenty years, and in recent years it has invested heavily in public cloud services.

Chinese companies have also augmented Southeast Asia’s e-commerce ecosystem, from Alibaba’s acquisition of Lazada in 2016 to the region-wide expansion of logistics and digital payments. AliPay+ and WeChat Pay, for example, are integrated in businesses across numerous Southeast Asian cities and as of December 2025, Singapore tourists in China can pay for purchases using digital renminbi linked to their local bank accounts. Already, Alibaba’s Lazada and ByteDance’s TikTok Shop command up to half of the e-commerce market share in Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines.

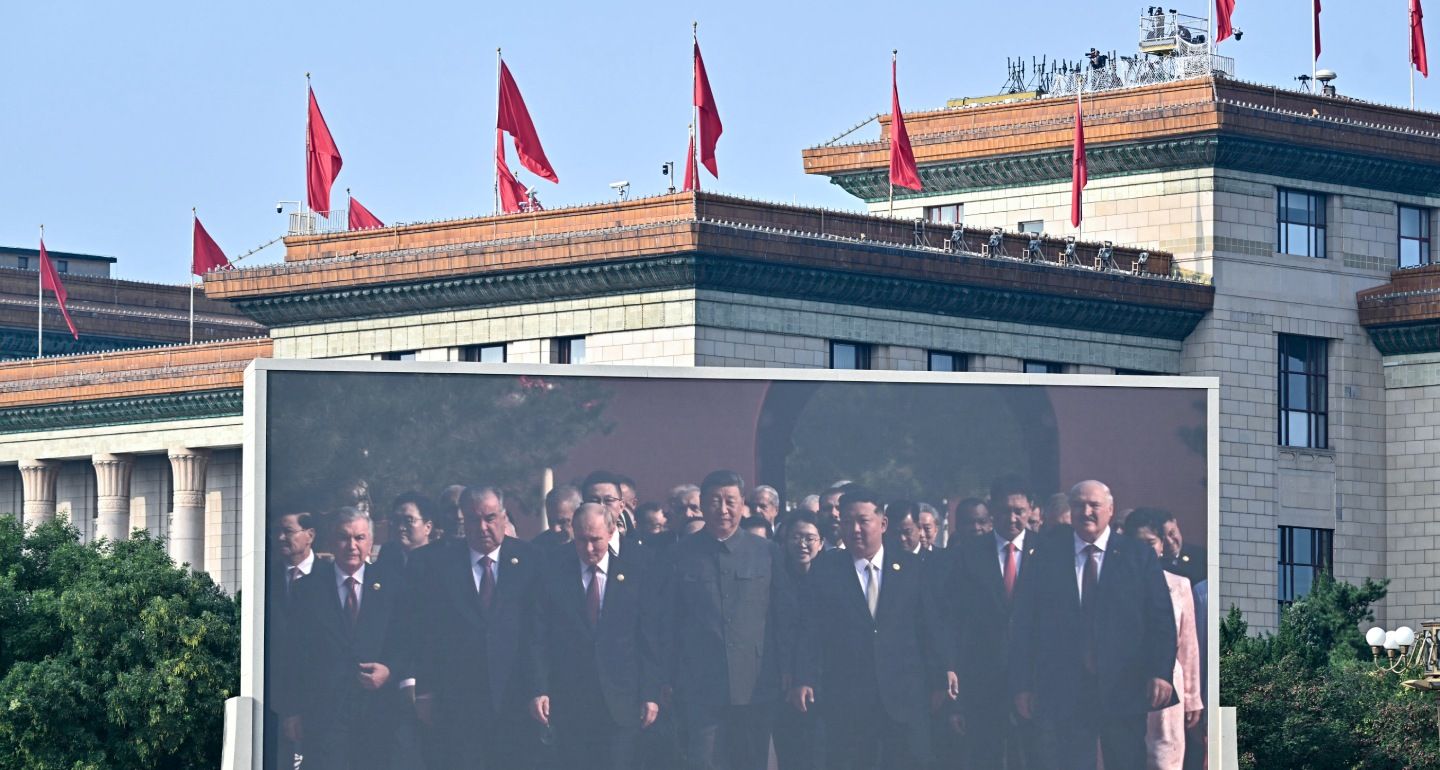

Importantly, these commercial linkages have been reinforced by institutions and frameworks. From Smart City cooperation to digital economy partnership, bilateral engagement is both formal and regular. Some of these initiatives incidentally facilitate China’s Digital Silk Road that offers to invest and build digital infrastructure in various Southeast Asian countries along the route.

Recognizing Risks is the First Step

But what’s commercial is now also political and geopolitical when it comes to technology. From 5G networks to subsea data cables and advanced semiconductors, it’s clear that Washington desires to exclude Chinese technology from global markets and supply chains and to restrict Chinese access to frontier technology. The fact that Chinese technologies are already embedded in ASEAN economies certainly does not sit well with Washington.

This of course raises risks for ASEAN countries. The risk on the U.S. side is that ASEAN countries are subject to economic coercion to not use Chinese products. The risk on the Chinese side is that ASEAN countries become overly dependent on the Chinese technology stack.

Subsea cables starkly illustrate the first risk. Washington’s lobbyingagainst Chinese suppliers in Southeast Asia’s cable plans highlights the politicization of infrastructure. This is often underwritten by the implicit threat of reduced investment or limited access to technologies that regional governments deem important for their countries’ digital economy goals. Similar pressures are building around semiconductor controls with countries such as Malaysia and Singapore caught between competing regulatory regimes.

On the second risk, China’s sheer scale across the digital value chain has raised concerns that overreliance on China can undermine ASEAN’s agency during moments of crisis (such as in the South China Sea) and weaken its economic leverage. Furthermore, persistent threats of cyberespionage and potential sabotage raise troubling questions about ASEAN’s vulnerability to other countries’ technologies.

Balancing the Scales

For ASEAN-China digital collaboration, three policy directions stand out to manage these growing risks.

First, despite U.S. arm-twisting, the reality is that partnerships between ASEAN countries and China continues apace. For instance, projects such as the Asia Direct Cable and the South-East Asia–Hainan–Hong Kong Express demonstrate ongoing collaboration in implementing redundancy contingencies for digital infrastructure. So while disengagement is simply a nonstarter, ASEAN-China digital cooperation should be subject to higher levels of scrutiny across the technical, security, and political risk domains.

Second, with the clear recognition that China has tremendous leverage on technology, ASEAN countries need to have a cohesive approach to digital cooperation with China. This means building on ASEAN-led mechanisms to streamline standards, pool regulatory capacity, and articulate shared priorities on data protection, competition, and regional autonomy. Presenting a “united front” on technology paradoxically will earn respect from China in its dealings with ASEAN. The recent upgrade of the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area affords an opportunity to embed principles of transparency, dispute management, and accountability in digital trade to prevent deepening cooperation from turning into dependency.

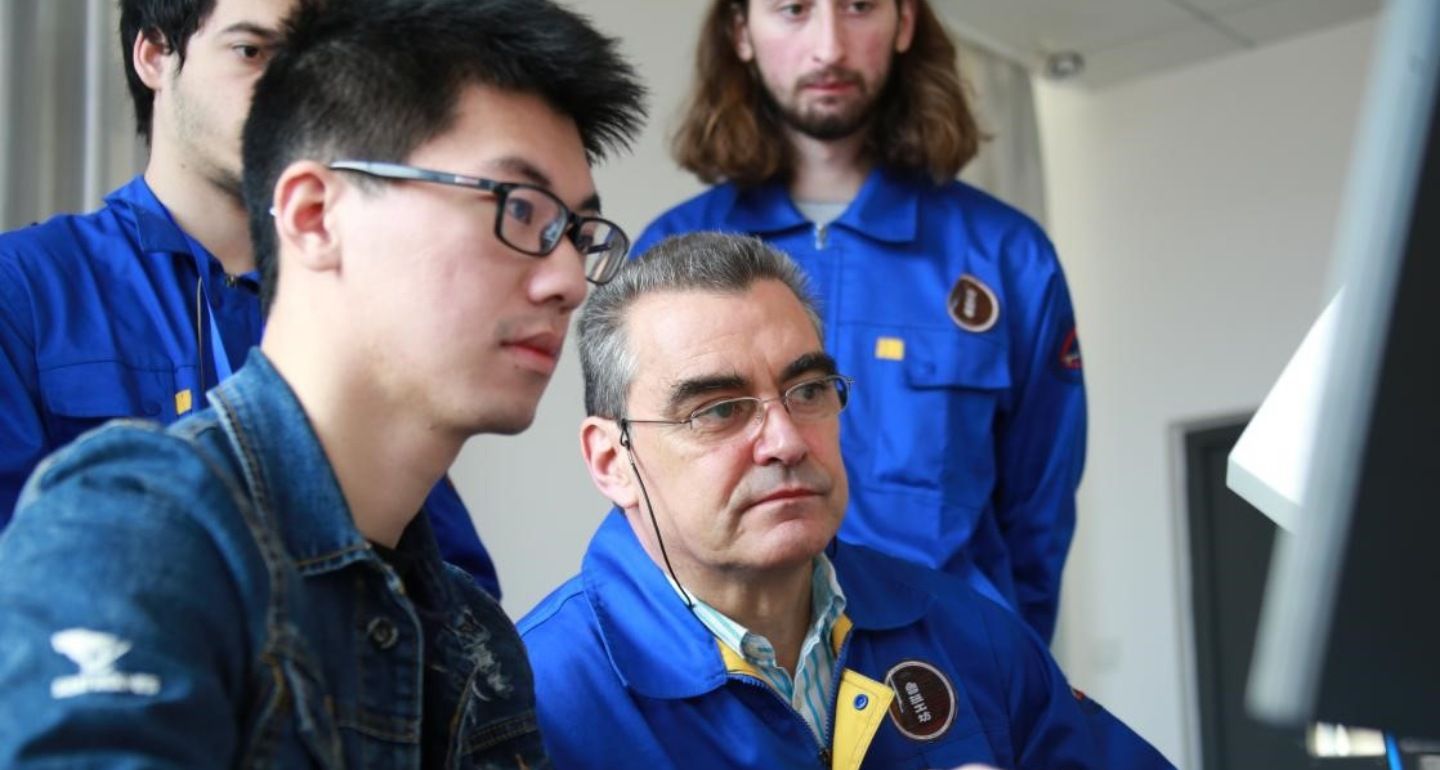

Third, beyond infrastructure, logistics, platforms, and applications, ASEAN and China should jointly shape digital governance frameworks. AI governance, in particular, is fast becoming the fault line between rule-makers and rule-takers. China’s recentcalls for a global AI cooperation organization and its emphasis on Global South collaboration provide an opportunity for ASEAN to engage proactively as an active stakeholder rather than a passive recipient of norms. Concrete collaboration between ASEAN and Chinese researchers, regulators, industry players, and civil society actors could include joint studies on AI impacts in emerging economies and accountability mechanisms for algorithmic harm across the entire life cycle of AI systems.

In an age where digital interdependence is being securitized, if not weaponized, ASEAN and China have a shared interest in proving that cooperation can be both strategic, stable, and equitable. Decades of habit-building between China and ASEAN provide a ready onramp for deeper but clear-headed collaboration. Whether both parties can demonstrate creative and beneficial cooperative models on technology that avoids reproducing tired patterns of extraction remains to be seen.