Nikolay Petrov

{

"authors": [

"Nikolay Petrov"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Caucasus",

"Russia"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform"

]

}

Source: Getty

The Medvedev Show

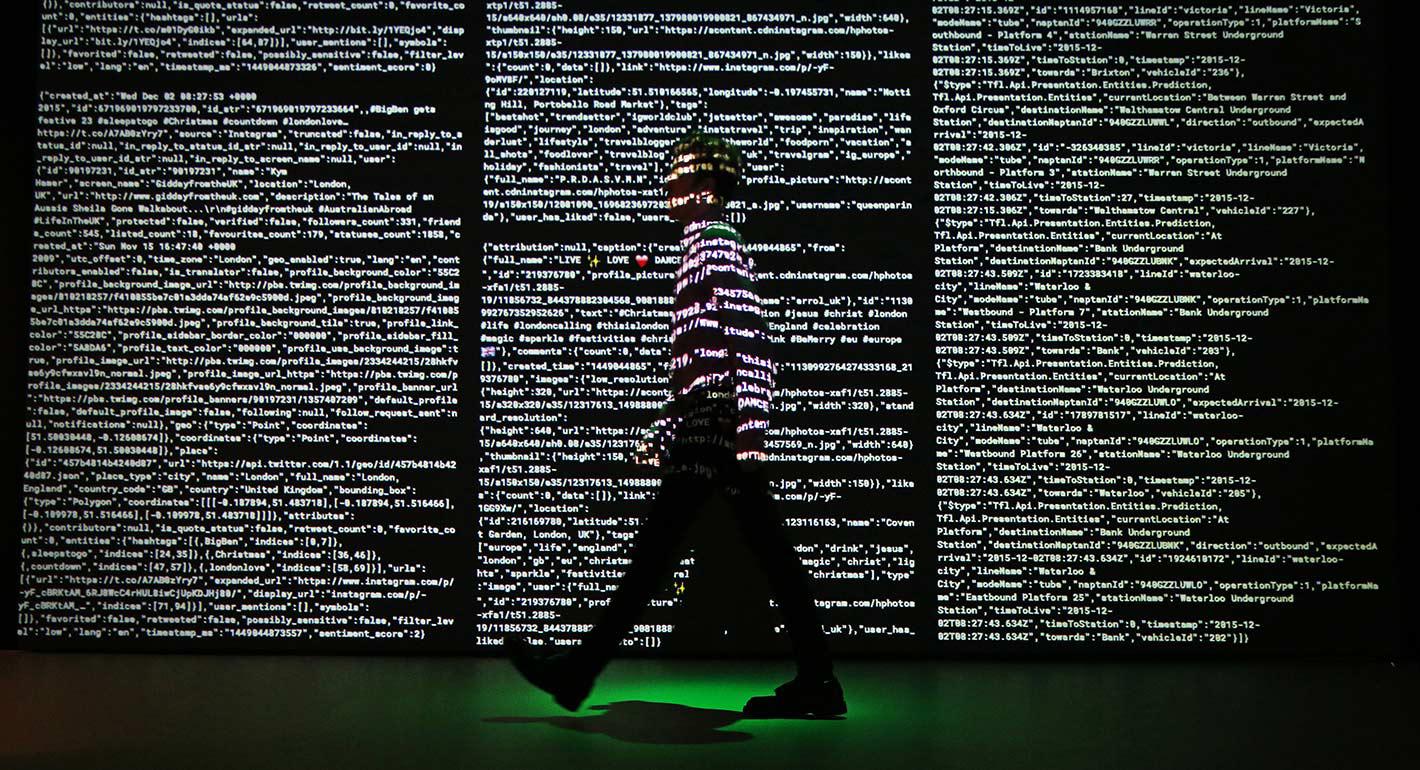

From Putin’s staged call-in show to Medvedev’s "citizens vs. officials" program, Russia’s virtual politics provides only the illusion of government transparency and improvement.

Source: The Moscow Times

As president, Putin put on a series of staged call-in shows that promised to provide citizens with a direct line to the president. By the end of his presidency, the annual televised shows had broken their own records for the number of questions sent in (2.5 million, or one for every 50 Russian citizens) and the number of questions answered by the president (dozens).

President Dmitry Medvedev, however, has not been able to manage a similar line of communication with the people, even with the careful selection of participants and the prior agreement of questions. So Medvedev has not followed in the path of his more telegenic and smooth predecessor with the call-in shows.

About the Author

Former Scholar-in-Residence, Society and Regions Program, Moscow Center

Nikolay Petrov was the chair of the Carnegie Moscow Center’s Society and Regions Program. Until 2006, he also worked at the Institute of Geography at the Russian Academy of Sciences, where he started to work in 1982.

- Moscow Elections: Winners and LosersCommentary

- September 8 Election As a New Phase of the Society and Authorities' CoevolutionCommentary

Nikolay Petrov

Recent Work

Carnegie India does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie India

- India’s Sustained Economic Recovery Will Require Changes to Its Bankruptcy LawPaper

As India’s economy recovers from the coronavirus pandemic, Indian businesses need efficient financial structures to regain their ground. Key reforms to India’s Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code could fill these gaps.

Anirudh Burman

- Cross-Border Data Access for Law Enforcement: What Are India’s Strategic Options?Paper

Access to cross-border data is an integral piece of the law enforcement puzzle. India is well placed to lead the discussions on international data agreements subject to undertaking necessary surveillance reforms.

Smriti Parsheera, Prateek Jha

- The BRI in Post-Coronavirus South AsiaArticle

After the coronavirus pandemic wanes, how will China’s reorientation of the Belt and Road Initiative to address global health concerns influence its relationships with South Asian countries?

Deep Pal, Rahul Bhatia

- India’s Unheeded Coronavirus WarningCommentary

Early in the outbreak, government researchers forecast several high-risk scenarios that were downplayed or ignored in public messaging.

Gautam I. Menon

- Intrusive Pandemic-Era Monitoring Is the Same Old Surveillance State, Not a New OneArticle

Governments around the world are turning to new forms of digital surveillance to monitor the spread of the coronavirus, though they are mostly using existing laws to do so.

Anirudh Burman