The recent African Cup of Nations tournament in Morocco touched on issues that largely transcended the sport.

Issam Kayssi, Yasmine Zarhloule

{

"authors": [

"Jake Walles",

"Sarah Yerkes"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Diwan",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "menaTransitions",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center",

"programAffiliation": "MEP",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [

"Tunisia Monitor"

],

"regions": [

"North Africa",

"Tunisia",

"Maghreb"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform"

]

}

Source: Getty

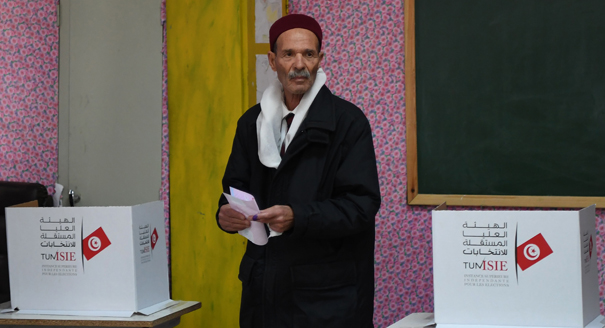

Tunisia’s local elections reflected public discontent, but were also an accomplishment.

Tunisians went to the polls on May 6 to elect members of 350 municipal councils in the country’s first free and fair local elections. Despite a disappointing turnout of only 35.6 percent, the elections, which had been repeatedly postponed due to logistical and political challenges, represented another accomplishment in Tunisia’s democratic transition. They were also the first significant step in the process of devolving power from the capital to the regions as envisaged by the 2014 constitution.

Independent lists representing a variety of interests bested the two major parties, Ennahda and Nidaa Tounes. These lists received 32.9 percent of the vote, compared to 28.6 percent for Ennahda and 22.17 percent for Nidaa Tounes, reflecting the population’s unhappiness with the political leadership in Tunis and the absence of economic growth. Overall, the elections demonstrated that Tunisia’s democratic transition continues to make progress but remains somewhat fragile, as seen in the low turnout and turn away from the traditional political parties. The next big test for the country will be the presidential and parliamentary elections, expected in 2019.

Despite the low turnout, Tunisia’s success in holding another successful election should not be underestimated. The municipal elections were judged free and fair by local and international observers and took place in a generally calm environment, despite an uptick in official propaganda by the Islamic State against Tunisia in the weeks before the voting. With four successful elections since the uprising in 2011, Tunisia has now completed the initial stages of establishing a democratic system. It has ratified a new constitution, elected a president and parliament, and has now taken a first major step toward decentralizing power and giving more authority to local representative bodies.

The trust gap between the government and the governed in Tunisia has been steadily growing, therefore the low turnout was not surprising. However, it was disappointing. The fact that roughly two-thirds of eligible voters stayed home was a strong message of protest. Estimated participation ranged from a high of 69.8 percent in a municipality in Monastir to a low of only 26 percent in the Tunis I region.

The low turnout also reflected the fragility of Tunisia’s democratic evolution and the strong popular disappointment with the government’s handling of the economy. The government of Prime Minister Youssef Chahed will not have much time to tackle the country’s economic problems before the country enters a new election cycle in 2019, assuming Chahed can stay in office for that long. If Tunisia fails to address its problems, the economic adjustments to remedy them will become harder and could negatively impact the country’s political progress.

One noteworthy aspect of the local elections was the positive step forward it achieved for gender equality and youth participation at the local level. The election law required both vertical and horizontal gender parity—a remarkable achievement for any democracy. A consequence of this is that around half of the 7,200 elected local officials are women. Furthermore, lists were required to include at least one person under the age of 35 within the top three spots, as well as a young person within each six additional spots. As a result, more than a third of those who were elected are under 35. These quotas are an important first step toward diversifying Tunisia’s political landscape. And hopefully, once in power, women and youths will be able to normalize inclusive politics to the point where Tunisia no longer needs quotas to achieve these results.

Just ten days before the May 6 vote, the National Assembly finally passed the long-delayed Organic Law on Local Government, defining the powers of municipalities and regional districts and their relationship with the central government. Implementation will be a challenge given Tunisia’s historically centralized system. However, for the first time local officials will now have a legal framework and legitimacy flowing from democratic elections to bolster their role in decisionmaking and resource allocation in their areas.

In a recent visit to Tunisia’s interior, one of the authors saw that residents were hopeful that the elections would result in more opportunities to participate in decisions that could improve their lives. They also hoped it would channel much-needed funds from the central government to their municipalities. If the central government genuinely allows power and resources to flow to the regions, decentralization could mark a fundamental change in how Tunisia is governed. Finally, the country would begin to address the unequal distribution of political and economic power among the regions. But for this to succeed, the public must be made aware of its rights and responsibilities regarding participatory democracy at the local level. Local officials must also work across local borders and with officials nationally to ensure that decentralization does not remain only nominal.

The outcome of the voting showed, paradoxically, both the continued strength of Ennahda and Nidaa Tounes, as well as their weakness. Ennahda was the only party with the resources to compete in all 350 municipalities, with Nidaa doing so in just under 350 municipalities. As expected, Ennahda did especially well in the main cities in the south of the country, and Nidaa Tounes in the Sahel cities of Monastir and Sousse. Ennahda will be especially pleased with its performance in Tunis, where its list appears to have secured the most seats on the municipal council, setting the stage for the election of the capital’s first female mayor, Sou‘ad Abderrahim, an Ennahda member. The dominance of the two largest parties will contribute to stability, at least in the short term, as both continue to share power and cooperate in implementing major policy decisions.

As political parties begin preparations for the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections, they would be smart to heed the warning signs from the local contests. The Tunisian public is looking for alternative leadership and may punish the major parties for failing to address the economic challenges that brought democracy to Tunisia in the first place.

Former Nonresident Senior Fellow, Middle East Program

Jake Walles was a nonresident senior fellow in the Middle East Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where he focuses on Israeli-Palestinian issues, Tunisia, and counterterrorism.

Senior Fellow, Middle East Program

Sarah Yerkes is a senior fellow in Carnegie’s Middle East Program, where her research focuses on Tunisia’s political, economic, and security developments as well as state-society relations in the Middle East and North Africa.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The recent African Cup of Nations tournament in Morocco touched on issues that largely transcended the sport.

Issam Kayssi, Yasmine Zarhloule

Mustaqbal Misr has expanded its portfolio with remarkable speed, but a lack of transparency remains.

Yezid Sayigh

The burden of environmental degradation is felt not only through physical labor but also emotional and social loss.

Yasmine Zarhloule, Ella Williams

The country’s youthful protest movement is seeking economic improvement, social justice, and just a little hope.

Yasmine Zarhloule

The Moroccan-Algerian rivalry is playing itself out in ties with Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali.

Yasmine Zarhloule