Mustaqbal Misr has expanded its portfolio with remarkable speed, but a lack of transparency remains.

Yezid Sayigh

{

"authors": [

"Dalia Ghanem",

"Ryad Benaidji"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Diwan",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [

"Arab Spring 2.0"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "menaTransitions",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center",

"programAffiliation": "MEP",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Maghreb",

"North Africa",

"Algeria"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform"

]

}

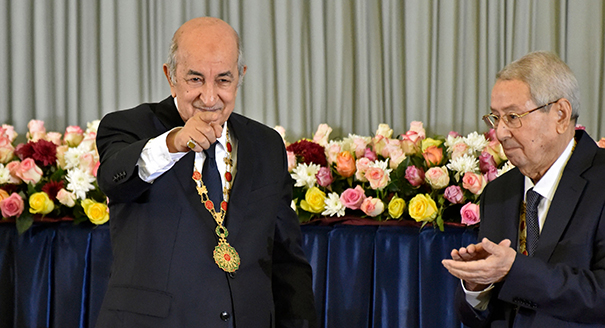

Source: Getty

Algeria’s new president has been going overboard to win the approval of a population that doesn’t want him.

In the shadow of massive demonstrations that have persisted for almost a year, Abdelmadjid Tebboun was elected president of Algeria on December 12. With an abstention rate that reached nearly 60 percent, the legitimacy deficit of the new president and his government is substantial over a month after he took office.

The highly contested Tebboun and the military have had to employ several methods to try to legitimize the president’s rule. That’s because since the election peaceful mass protests have continued. Students are continuing to take up to the streets every Tuesday and the general population every Friday. Protesters accuse Tebboun of being a man of the system, a member of what is called “the gang,” meaning the political insiders and oligarchs associated with previous regimes, whose son is in prison over a cocaine trafficking scandal.

In response to these accusations, Tebboun has placed the “moralization of political life” and the “separation between money and politics” at the top of his government’s priorities. He has promised to continue fighting corruption as he did when he was briefly prime minister in 2017, and to set up mechanisms to avoid conflicts of interest by public officials. This is an important feature of the “new republic” he has promised to put in place.

While Algeria is facing long-term economic paralysis, Tebboun seeks to diversify an unproductive economy that relies heavily on hydrocarbons and imports. He has also promised an economic model that would cut red tape and is capable of reducing unemployment and providing food security. Yet he has also insisted on the need to bolster social services that help the most impoverished segment of the population—about 30 percent of Algerians according to him. He has also promised to eliminate taxes on the most vulnerable in society.

Tebboun has announced that he would respond to one of the main demands of the popular movement and revise the constitution. He has promised a constitution that strengthens rights and freedoms, fights corruption, consolidates the separation of powers, reinforces parliament’s prerogatives, and guarantees equality of citizens (with, in particular, the potential repeal of Article 51 that excludes citizens with dual nationality from participating in political life).

On January 8, the presidency established a committee of experts made up mainly of law professors that will submit new proposals within two months. The committee will consult with political actors and civil society organizations and its proposals will be presented to parliament for adoption. Once approved, Algerians will be invited to vote by referendum on the revisions. For the protestors, however, the revisions should not be prepared by a committee of experts. Rather, they believe it is the sovereign right of the people.

Tebboun’s effort to legitimize himself was also apparent in his ministerial appointments. He chose an academic as prime minister and several former university professors as well as others from civil society as ministers. He also wants to create, or at least give the impression of creating, a new style of governance. For example, he has asked not to be called “Your Excellency,” as were his predecessors, and has promised to hold regular press conferences in order to govern with transparency.

The new president has also made claims about national identity, order, and security to try to reinforce his credibility. He has used Algeria’s war of independence to bolster a strong sense of national identification. At his inauguration, Tebboun linked the generation of November 1954, when the liberation war began, with that of February 22, 2019, when mass protests took place throughout Algeria against a renewal of the term of then-president ‘Abdelaziz Bouteflika. According to Tebboun, the protestors of today are a continuation of the first generation of Algerians who fought for independence.

The president has also praised the achievements of the People’s National Army (PNA), which he described as the “backbone of the nation” that had “protected the hiraq,” or protest movement. The same rhetoric has also been used by the new PNA chief of staff, Sa‘id Chengriha, who has also denounced supposed “dangerous plots” organized by “dark forces” and “foreign hands.” By this he implied that countties such as the United States, France, and Morocco were helping internal forces such as Islamists and Berber separatists with the aim of destabilizing Algeria.

The authorities have gone so far as to claim that they had dismantled a “sabotage plan” by the Movement for the Autonomy of Kabylia (MAK) prior to the presidential election. Their aim was to spread a narrative according to which the MAK is a well organized and violent group ready to exploit the protest movement to create chaos. The authorities prevented the MAK from holding an annual new year’s march on January 12, and on January 13 the government was ordered to prepare a bill preventing expressions of hatred and regionalism online. In these ways the authorities have sought to justify repression and artificially revitalize national unity by identifying purported enemies both inside and outside Algeria.

Given the latest developments in neighboring Libya, the military has also sought to highlight its role as the “protector of the integrity of the borders.” Tebboun’s role in helping to resolve the Libyan conflict was enhanced last week when he received the head of the Libyan Government of National Accord, Fayez al-Sarraj and Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu. He also participated in the Berlin conference on Libya on January 17, to which he was officially invited by German Chancellor Angela Merkel. During the conference, Tebboun stated that Algeria was ready to host talks between the “Libyan brothers.”

These visits and Algiers’ involvement in a potential Libyan settlement reflect the desire of the Algerian authorities to make up for lost time after years of stagnant diplomacy. Such activities are also a tool to manufacture domestic legitimacy for the regime as well as international credibility.

Tebboun’s efforts are not so different than his predecessor’s. However, when Bouteflika came to power in 1999, the increase in oil revenues led to a rise in living standards and the subordination of the business class to the president and his entourage. Today, this is hard to reproduce because of adverse economic conditions, but also because Algerians are no longer willing to accept a model of leadership that produced not legitimacy, but support through dependency.

The legitimacy crisis will be aggravated by the government’s inability to live up to the socioeconomic expectations of the population and implement the systemic political changes for which Algerians are calling. The time when regular elections and referendums allowed regimes to maintain a democratic facade and engender legitimacy is over. The idealization of the people by the leadership in its public statements while showing disdain for popular demands in practice is something Algerians will simply not accept anymore.

* Ryad Benaidji is a journalist at the EBRA press group in Paris

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Mustaqbal Misr has expanded its portfolio with remarkable speed, but a lack of transparency remains.

Yezid Sayigh

The burden of environmental degradation is felt not only through physical labor but also emotional and social loss.

Yasmine Zarhloule, Ella Williams

The country’s youthful protest movement is seeking economic improvement, social justice, and just a little hope.

Yasmine Zarhloule

The Moroccan-Algerian rivalry is playing itself out in ties with Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali.

Yasmine Zarhloule

In an interview, Yasmine Zarhloule discusses irregular migration to Europe and the shortcomings of a securitization policy.

Rayyan Al-Shawaf