- +1

Rudra Chaudhuri, Tejas Bharadwaj, Konark Bhandari, …

{

"authors": [

"Shruti Sharma"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie India"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie India",

"programAffiliation": "TIA",

"programs": [

"Technology and International Affairs"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Iran"

],

"topics": [

"Technology"

]

}

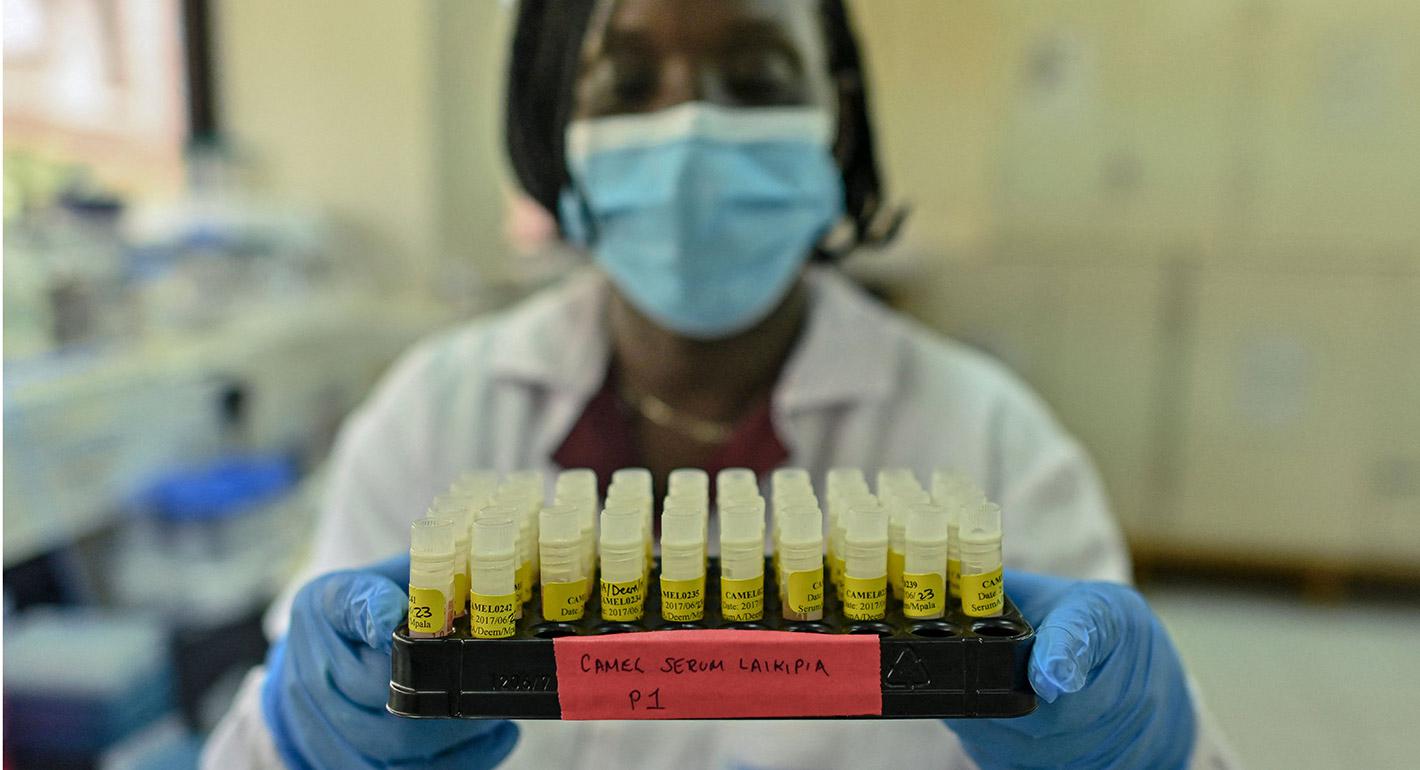

Source: Getty

How Should Countries Study Viruses Safely?

The uncertain origin of the coronavirus has focused attention on gain-of-function research—studying viruses to learn how they spread. How can countries work together to ensure stringent safety standards?

It has been almost a year and a half since the new coronavirus was first detected in the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, China. The precise origin of the virus remains obscure. While some scientists believe that the virus jumped from an animal host to humans, others believe that the new pathogen was accidentally released from the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV). To understand the origin of the coronavirus pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) organized an international team of scientists who visited Wuhan early this year.

The team was unable to make a firm conclusion. Its report stated that the virus “most likely” originated from natural sources and the possibility of a lab leak was “extremely unlikely.” The director general of the WHO observed in a public address that “[f]inding the origin of a virus takes time and we owe it to the world to find the source so we can collectively take steps to reduce the risk of this happening again. No single research trip can provide all the answers.” With the WHO beginning the next phase of its origin study, it is important to understand whether and how finding the source of this pandemic matters as India and other countries revisit their public health preparedness strategies and plans.

Why Is It Important to Trace the Origins of the Coronavirus Pandemic?

Finding the origin of the coronavirus pandemic is important in either scenario.

First, if the virus originated naturally, tracing its origin will help to explain its spread and its potential evolution. Knowing the source of the virus will aid in deciphering the conditions that lead to natural transmission from animals to humans. It will also help in anticipating and preventing the spread of similar viruses in the future.

Second, if the virus escaped from the lab, tracing its origin will help to avoid future lab accidents, informing guidelines for experiments and reforming biosafety and biosecurity regulations. Biosafety accidents are a known peril, with examples including the release of the virus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) from a Chinese lab, killing one person and infected eight others, and an accidental release from a company manufacturing brucellosis vaccines in China that infected more than 3,000 people in 2019. In another instance, a researcher in India was accidentally infected with the buffalopox virus; in Singapore a researcher was infected with SARS due to inadvertent cross-contamination of viral samples.

Despite limited evidence to prove that this pandemic was a result of accidental mishap, it is important to understand the purpose of research that manipulates the nature of the virus and its relevance with respect to the coronavirus pandemic. Such experiments commonly fall under the category of gain-of-function (GOF) research.

What is Gain-of-Function Research?

GOF research manipulates the genetic code of an organism to confer a new ability, such as creating drought resistant plants or producing mosquitoes resistant to spreading malaria. With respect to the origin of the novel coronavirus, GOF research refers to experimentation that enhances the potency of a virus. GOF research “improves the ability of a pathogen to cause disease, [to] help define the fundamental nature of human-pathogen interactions, thereby enabling assessment of the pandemic potential of emerging infectious agents, informing public health and preparedness efforts, and furthering medical countermeasure development.” It is conducted around the world to understand a pathogen’s virulence and/or its transmissibility. For example, in 2006, scientists at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted studies to understand how Asian bird flu can spread among humans. Similar studies were conducted by a group of scientists who altered the avian influenza virus to make it more transmissible among mammals.

Recognizing the risk that GOF experiments might result in an accidental release and outbreak, the U.S. government in 2014 temporarily stopped funding GOF studies. The government also encouraged researchers—whether federally funded or not—to voluntarily stop such research until the risks and benefits of these experiments were reassessed. As a result of that process, federal funding was reinstated for GOF studies in 2017, with a new multi-disciplinary review process required. Similarly, an advisory council in Europe suggested pursuing necessary safeguards and policies to allow for a case-to-case evaluation of GOF experiments. European researchers must justify the objectives of their research to the institution where the experiment will be carried out, their funding agencies, appropriate ethics committees, and relevant national authorities. Thus, the support for GOF research in most countries depends on the researchers’ ability to satisfy additional review and process controls.

Even though there is no evidence that GOF experimentation was involved in producing the novel coronavirus, the pandemic has renewed debates around the safety of such research.

What Is the Way Forward to Regulate Such Research?

Since GOF research is crucial to developing medical countermeasures, a blanket moratorium on such experiments might be counterproductive. Given the risks, however, stringent oversight is needed. And, if oversight is not coordinated or consistent worldwide, all societies will be more vulnerable than they should be, given the distributed consequences of a potential pandemic. The weakest link can threaten all the others in the chain.

There are three possible approaches to regulating such experiments in the future.

First, in countries with a significant biotech industry, a national nodal agency can be set up for transparent review of all GOF experiments prior to their initiation. Review is necessary to ensure that such experiments are being conducted to only address public health questions and to validate if GOF research is the best way to answer them. Such an agency could be responsible for periodic monitoring of such experiments, tracking incidents of laboratory-acquired infections (if any), and reporting incidents to the concerned international organizations. This oversight is crucial because a single safety breach can spark a pandemic.

Second, given the possibility of pandemics emerging from GOF experiments, countries should now start the inevitably long process of negotiating an international treaty under the WHO to regulate GOF research. Such a treaty could establish criteria that all nations would be expected to follow in regulating the safety of GOF research. It could also outline minimum certification and validation requirements for labs that conduct such research or perhaps advise restricting such studies to labs that have exceptional biosafety and biosecurity records. Given the Indian government’s traditional wariness toward treaties initiated by others, and the significant role of India’s biotech industry, India should help lead this negotiation.

Third, regardless of the source of the COVID-19, the pandemic has revealed the value of global monitoring and information sharing related to public health and to understanding the origins of disease. While all countries are obligated to report to the WHO naturally occurring diseases that have the potential to cross borders, it is important to expand the mandate of the surveillance mechanism to include laboratory-acquired infections. The Implementation Support Unit associated with the UN’s Biological Weapons Convention could provide a practical mechanism for coordinating with the proposed nodal agencies and the WHO on monitoring and investigating possible incidents.

Conclusion

The uncertainties and debates about the origins of the coronavirus pandemic remind us that infectious disease outbreaks can arise naturally or from a laboratory. It is important to manage, if not pre-empt, both kinds of risk and to build robust global processes, including strict oversight of GOF experiments, to minimize the risks of outbreaks occurring due to laboratory accidents. Collective action at a national level can benefit people globally.

About the Author

Former Associate Director, Fellow, and Chief Coordinator, Global Technology Summit, Technology and Society Program

Shruti Sharma was an associate director and a fellow with the Technology and Society Program at Carnegie India, where she is currently working on exploring the challenges and opportunities in leveraging biotechnology to improve public health capacity in India. Additionally, she is the Chief Coordinator of Carnegie India's Global Technology Summit.

- The India-United Kingdom Technology and Security Initiative: Ideas for ChangeArticle

- The India-U.S. TRUST Initiative: A Resilient Pharma Supply ChainCommentary

Shruti Sharma

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Iran Is Pushing Its Neighbors Toward the United StatesCommentary

Tehran’s attacks are reshaping the security situation in the Middle East—and forcing the region’s clock to tick backward once again.

Amr Hamzawy

- The Gulf Monarchies Are Caught Between Iran’s Desperation and the U.S.’s RecklessnessCommentary

Only collective security can protect fragile economic models.

Andrew Leber

- Europe on Iran: Gone with the WindCommentary

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

- India Signs the Pax Silica—A Counter to Pax Sinica?Commentary

On the last day of the India AI Impact Summit, India signed Pax Silica, a U.S.-led declaration seemingly focused on semiconductors. While India’s accession to the same was not entirely unforeseen, becoming a signatory nation this quickly was not on the cards either.

Konark Bhandari

- What We Know About Drone Use in the Iran WarCommentary

Two experts discuss how drone technology is shaping yet another conflict and what the United States can learn from Ukraine.

Steve Feldstein, Dara Massicot