The simultaneous condemnation of Chinese cyber attacks by the Five Eyes allies (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK, and the United States) plus the EU, NATO, and Japan was an unprecedented moment of unity in calling out unacceptable behavior in cyberspace. Nevertheless, Beijing fell back on its standard response to public attribution of state-sponsored cyber attacks, dismissing the criticism as “groundless accusations out of thin air” while accusing the United States of even worse behavior.

To generate real momentum toward red lines and a broader consensus on how states should exercise power in cyberspace, the reproof should be used as an opportunity to give substance to the UN norms recently agreed by twenty-five states, including China.

A Missed Opportunity

The Microsoft Exchange attack was most likely the catalyst for the allies presenting a united front. While the public statements varied in emphasis, all identified threat actors linked to the Chinese Ministry of State Security as the perpetrators of a mass exploitation of vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange Server in early 2021. The UK described the operation as “systematic cyber sabotage” that was part of a “reckless but familiar pattern of behavior.”

Unfortunately, the statements stopped there, falling short of identifying specifically why the Microsoft attack warranted an unprecedented public rebuke. It is reasonable to assume that they were motivated by the systemic importance of email to the functioning of modern economies and societies, coupled with the indiscriminate nature of the attack. If that was the case, there was a missed chance to test the application of the cyber norms that China has endorsed through the UN Group of Governmental Experts (GGE).

Why Attacking Email Is So Damaging

The May 2021 GGE report showcased agreement to a norm (13i) that “states should take reasonable steps to ensure the integrity of the supply chain so that end users can have confidence in the security of information and communications technology (ICT) products.” The Microsoft attack breached tens of thousands of machines and networks worldwide, exposing organizations because of their reliance on particular email servers. Arguably, this incident presents a powerful test of the international consensus against indiscriminate supply chain attacks. Had the allies made this a central component of their complaint, Beijing would have found it harder to dismiss the allegations with its standard rhetoric.

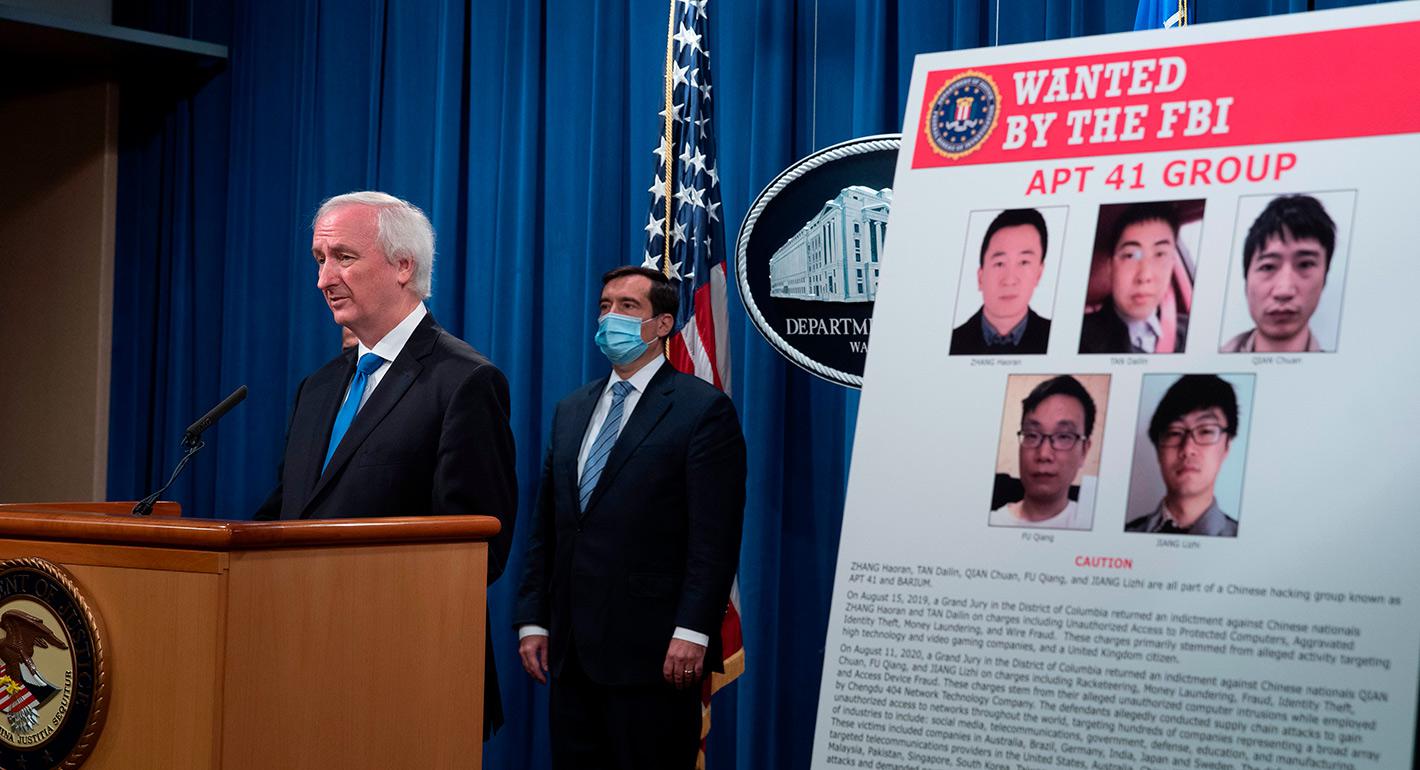

Government Hacks By Day, Cyber Crime By Night

Beyond the Microsoft attack, the statements only aligned on the general condemnation of China’s behavior in cyberspace. But the GGE has produced agreements that could have further supported other aspects of the complaints. For example, the United States was alone in highlighting “unsanctioned” criminal activity for personal profit by Chinese government-affiliated cyber operators. While the other parties chose not to highlight this in their statements, the threat from actors who hack for the Chinese state by day and for their own criminal gain by night is well understood—the cyber crime group APT41 is a prominent example.

The GGE process has created norms against enabling criminal activity: the GGE’s 2015 report reached an agreement that “states should not knowingly allow their territory to be used for internationally wrongful acts using ICT.” The allies missed an opportunity to test that norm and root the accusation within an international consensus, if only to test the Chinese interpretation of the GGE norms it has signed on to.

Condemn the Act, Not Just the Perpetrators

Public attribution of cyber attacks clearly antagonizes Chinese leaders, who see it as part of a concerted campaign of multi-pronged hostility from Washington and U.S. allies. Accusations of irresponsible behavior in cyberspace by Chinese state actors are therefore framed and dismissed as a product of hostility to China. If public naming and shaming is to serve a strategic purpose beyond addressing domestic political audiences, it should focus on the characteristics of the unacceptable behavior, rather than solely its perpetrators.

The U.S. statement described indiscriminate supply chain attacks, criminal activities by state operatives, and theft of intellectual property as unacceptable. If the United States and its allies wish to establish red lines around these activities, their assessments should characterize specific forms of behavior as unacceptable, according to universally agreed principles. That way, Washington could achieve its strategic goals through a multinational consensus. The alternative is tit-for-tat rhetoric, which allows public attribution to be easily dismissed as a political blunt instrument.