Evan A. Feigenbaum

{

"authors": [

"Evan A. Feigenbaum"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie China"

],

"collections": [

"Belt and Road Initiative"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "asia",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "AP",

"programs": [

"Asia"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"East Asia",

"China",

"Central Asia",

"Turkmenistan"

],

"topics": [

"Economy",

"Foreign Policy"

]

}

Source: Getty

China Didn’t Invent Asian Connectivity, May, 14, 2017

China hopes to use three strengths to make the Belt and Road Initiative a success: its large foreign exchange reserves, dominance in certain infrastructure fields, and unique forms of state backed project finance.

Source: CNBC

Speaking on CNBC, Carnegie’s Evan Feigenbaum explained that China already had major projects underway in Central Asia even before announcing its “One Belt One Road” (OBOR) plan. He noted that China has “upped the game,” in terms of connectivity, but it did not invent the concept of Asian connectivity. This idea, he said, has a long history; it did not begin in 2013 nor, he added, did it spring from the mind of Xi Jinping like Athena emerging from Zeus’s head. Instead, he argued, it needs to be looked at organically as the product of the actions and choices of many players in Asia, including Japan, India, and the international financial institutions.

Feigenbaum argued that China hopes to leverage three main strengths to make its OBOR strategy a success. First, he said, the government has access to a “huge pile” of foreign exchange reserves that it hopes to leverage by ploughing it into direct investments and infrastructure projects; thus vehicles like the Chinese Silk Road Fund are capitalized in part or in whole by the state foreign exchange administrator. Second, Chinese companies dominate certain areas of infrastructure, for example hydropower. Finally, he said, China can employ unique forms of state backed project finance—a model that Beijing knows few other countries or banks can compete with. One area to watch, he noted, is the degree to which China uses OBOR projects to export its indigenous engineering standards and thus make them de facto global standards.

The United States, Feigenbaum continued, is missing in action on connectivity in Asia; it is reactive instead of proactive and on defense instead of offense. He contended that Washington needs to think about how to better deploy its strengths rather than an apples to apples approach to China’s initiatives. The United States has a different model, distinct strengths, more leverage than it thinks, he continued, and doesn’t do state-backed China-style project finance. But ultimately, he said, the inevitably more integrated Asia is making the United States less relevant in large swathes of the region except as a security provider. So Washington had better figure out how to get more skin in the game, and quick, he concluded.

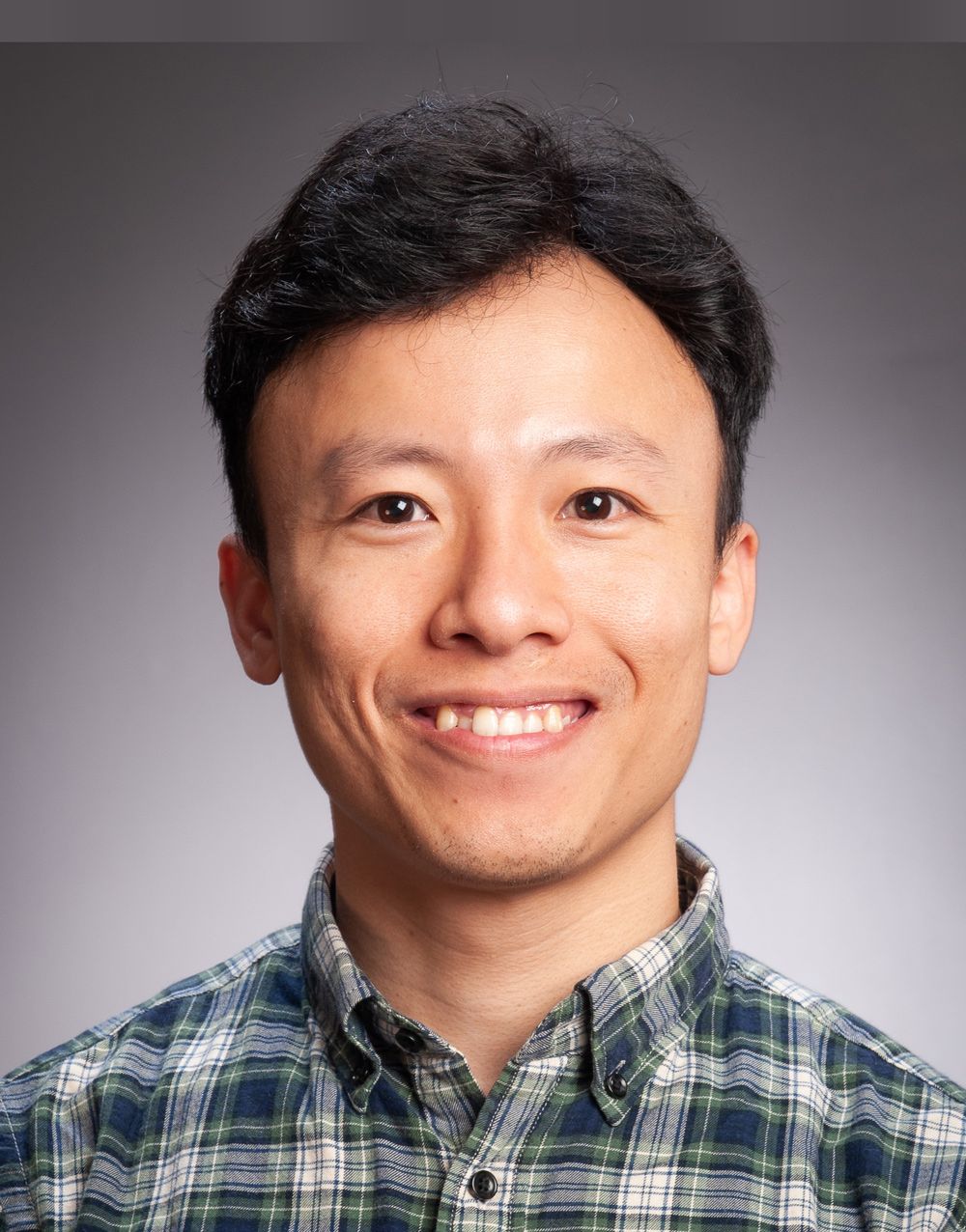

About the Author

Vice President for Studies

Evan A. Feigenbaum is vice president for studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where he oversees work at its offices in Washington, New Delhi, and Singapore on a dynamic region encompassing both East Asia and South Asia. He served twice as Deputy Assistant Secretary of State and advised two Secretaries of State and a former Treasury Secretary on Asia.

- Beijing Doesn’t Think Like Washington—and the Iran Conflict Shows WhyCommentary

- The Trump-Modi Trade Deal Won’t Magically Restore U.S.-India TrustCommentary

Evan A. Feigenbaum

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie China

- Malaysia’s Year as ASEAN Chair: Managing DisorderCommentary

Malaysia’s chairmanship sought to fend off short-term challenges while laying the groundwork for minimizing ASEAN’s longer-term exposure to external stresses.

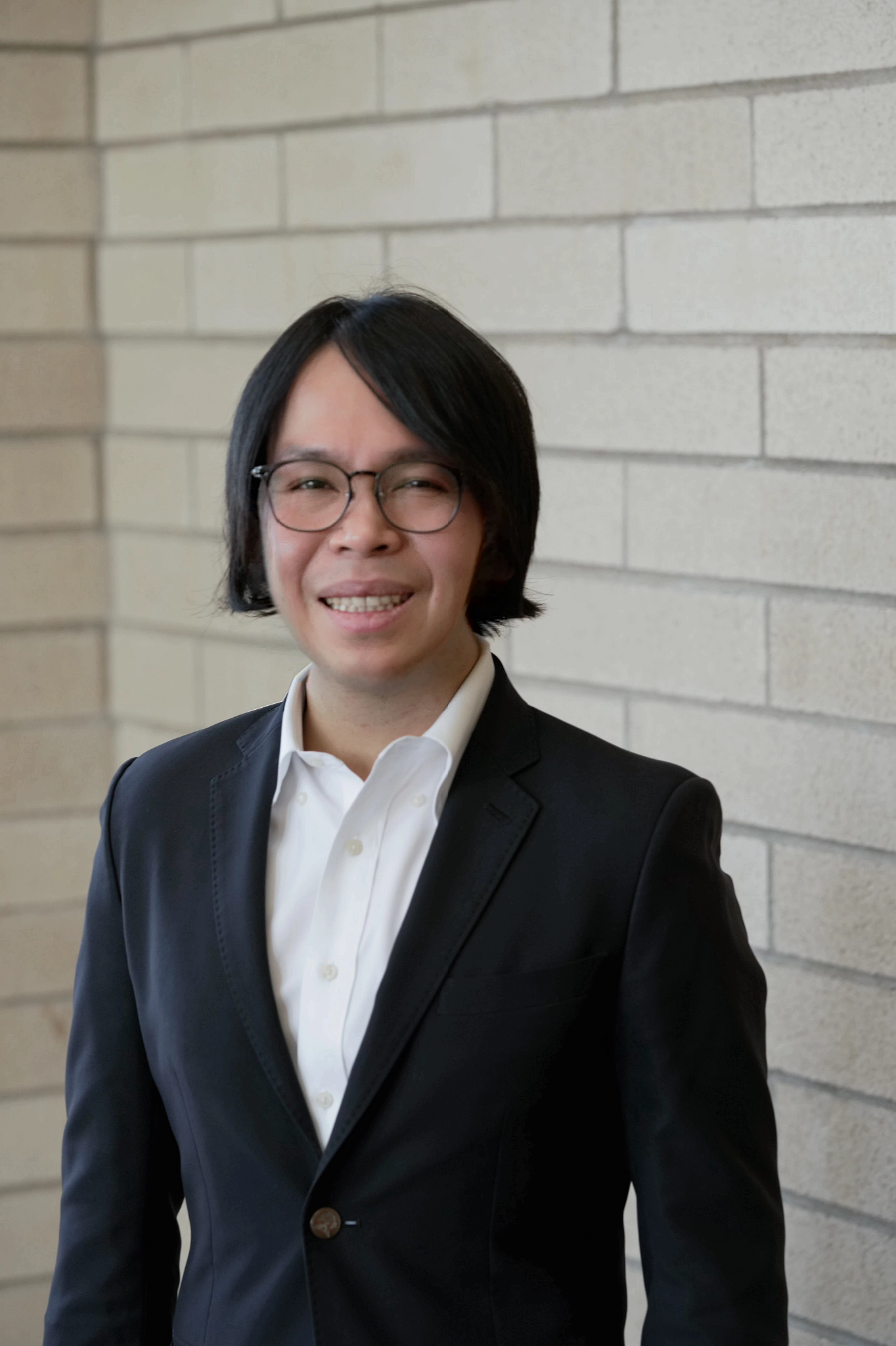

Elina Noor

- When It Comes to Superpower Geopolitics, Malaysia Is Staunchly NonpartisanCommentary

For Malaysia, the conjunction that works is “and” not “or” when it comes to the United States and China.

Elina Noor

- ASEAN-China Digital Cooperation: Deeper but Clear-Eyed EngagementCommentary

ASEAN needs to determine how to balance perpetuating the benefits of technology cooperation with China while mitigating the risks of getting caught in the crosshairs of U.S.-China gamesmanship.

Elina Noor

- Neither Comrade nor Ally: Decoding Vietnam’s First Army Drill with ChinaCommentary

In July 2025, Vietnam and China held their first joint army drill, a modest but symbolic move reflecting Hanoi’s strategic hedging amid U.S.–China rivalry.

Nguyễn Khắc Giang

- Today’s Rare Earths Conflict Echoes the 1973 Oil Crisis — But It’s Not the SameCommentary

Regulation, not embargo, allows Beijing to shape how other countries and firms adapt to its terms.

Alvin Camba