Malaysia’s chairmanship sought to fend off short-term challenges while laying the groundwork for minimizing ASEAN’s longer-term exposure to external stresses.

Elina Noor

{

"authors": [

"Cornelius Adebahr"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Europe"

],

"collections": [

"Transatlantic Cooperation",

"Europe’s Southern Neighborhood",

"Iranian Proliferation"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Europe",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [

"Europe"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Middle East",

"Europe",

"North America",

"Iran"

],

"topics": [

"Foreign Policy",

"Security",

"Nuclear Policy"

]

}

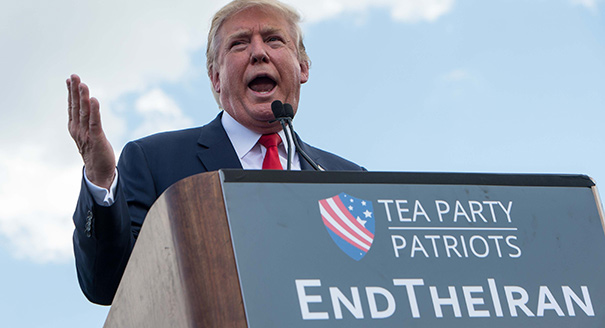

Following the election of Donald Trump as U.S. president, it falls to the Europeans to defend the international agreement on Iran’s nuclear program.

Source: El País

During his campaign, U.S. President-elect Donald Trump did not elaborate much on his foreign policy agenda. Yet he was very vocal about a few things: next to obliterating the so-called Islamic State and starting a trade war with China, Trump declared to “dismantle the disastrous deal with Iran.” This agreement, which put an end to Tehran deceiving the world about its nuclear program, is not only one of the few successes of European foreign policy. It is also an expression of how to collectively, and ultimately successfully, deal with a global challenge.

With Trump’s election, it now falls to the Europeans—as the initiators of a decade-long diplomatic process—to defend this historic accord. His rhetoric suggests that this will be an uphill battle.

In the United States, the idea that there could be a better deal was widespread but finally rebuked after intense debate following the signing of the agreement in July 2015. Those who want to undo the deal prefer a different solution to the problem altogether: either by forcing Iran to its knees through increased economic isolation or by ridding the country of its nuclear infrastructure—and possibly its regime—through military intervention. Just look at Cuba and Iraq to see how well those approaches have worked.

The deal, imperfect as it is, is still the best solution to the threat that Iran’s clandestine nuclear activities posed both to the nonproliferation regime and to neighbors like Israel. It is the collective expression of the interests of all its signatories, including China, France, Germany, Iran, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union. Moreover, it is underwritten by a resolution of the UN Security Council. Altogether, the deal carries as much international legitimacy as one can get.

This landmark deal will have been in force and faithfully implemented by all parties for one year—almost to the day—by the time that Trump swears the oath of office. Beyond the mere fencing in of Iran’s nuclear program, it embodies a global understanding of how the world (ideally) should be run: through compromise and commonly agreed rules that all actors subscribe to and which, if violated, are backed up by a harsh, multilateral sanctions regime. In turn, the agreement also stands for how its signatories relate to this world order—whether they feel bound by it or not. This carries particular significance for Iran, the United States, and the EU.

As a revolutionary state, the Islamic Republic has long been unsure about whether to oppose the current global system or to try to improve its position within it. The nuclear file is an illustration of this ambiguity: Iran defied the UN Security Council for nearly a decade all while taking pains to argue that its actions were within the confines of the nonproliferation regime. Moreover, Tehran has seen its share of domestic controversy over the deal, with a presidential election looming next spring that could turn into a referendum on the accord.

The United States, too, has a history of violating globally agreed rules when it has served its interests, despite being a founder and presumed guardian of the post–World War II order. After all that has been heard from candidate Trump on the campaign trail and in the immediate aftermath of his electoral victory, the question of national sovereignty vs. global rules will be front and center from the beginning of his presidency.

The Europeans, in contrast, cannot thrive but in a multilateral, rules-based environment. The EU is not a powerful nation-state that can rally its citizens around a shared destiny; instead, it will struggle even to uphold its unity given the UK’s vote to leave the union and, relatedly, the rise of populism throughout the continent. Moreover, they will have to face a lot of differences with the next U.S. president, from maintaining the transatlantic alliance and confronting Russia to dealing with the Middle East and climate change.

Preserving the Iran deal, by ensuring full compliance from all sides with both its letter and its spirit, is in the EU’s genuine interest. Together, the Europeans should hold the incoming U.S. administration accountable to it as much as they have held Tehran accountable, for the sake of not only the nonproliferation regime but also the rules-based global order without which Europe has no role to play in the world.

This article was originally published by El País in Spanish with the title “Contener a Trump.”

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Malaysia’s chairmanship sought to fend off short-term challenges while laying the groundwork for minimizing ASEAN’s longer-term exposure to external stresses.

Elina Noor

For Malaysia, the conjunction that works is “and” not “or” when it comes to the United States and China.

Elina Noor

In July 2025, Vietnam and China held their first joint army drill, a modest but symbolic move reflecting Hanoi’s strategic hedging amid U.S.–China rivalry.

Nguyễn Khắc Giang

The Thai-Cambodian conflict highlights the limits to China's peacemaker ambition and the significance of this role on Southeast Asia’s balance of power.

Pongphisoot (Paul) Busbarat

Beijing believes that Washington is overestimating its own leverage and its ability to handle the trade war’s impacts.

Rick Waters, Sheena Chestnut Greitens