Aron Lund

{

"authors": [

"Aron Lund"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Diwan",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Middle East",

"Iran",

"Syria",

"Lebanon"

],

"topics": []

}

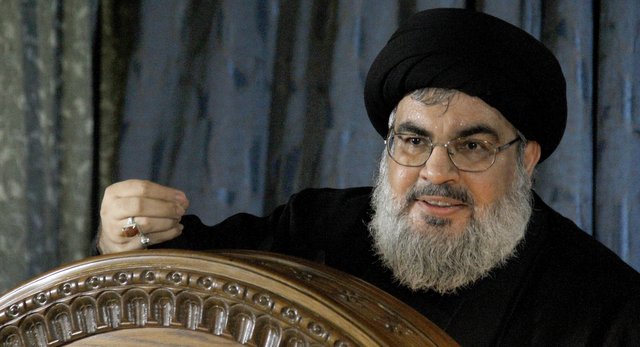

Source: Getty

Iran’s Unrealistic Endgame in Syria

Until Iran and all the other governments currently fanning the flames of war in Syria have accepted that no peace plan can work without a critical mass of armed actors on both sides, Syria’s slow collapse into Somalia-style anarchy will continue.

On March 22, the Egyptian Foreign Minister Nabil Fahmy met in Beirut with Lebanon’s minister of industry, Hussein Hajj Hassan, who also represents Hezbollah, Lebanon’s powerful Iranian-backed Shia Islamist movement. The group doesn’t only influence Lebanese policy via the government; it is also fighting in Syria alongside Iranian special forces and Iraqi Shia militias to prop up the government of President Bashar al-Assad. And it’s doing quite well at that.

Hezbollah Says Assad Won

Recent army advances in Syria around Aleppo and Homs and in the Qalamoun area have been presented by the Hezbollah leadership as steps on the road to victory. The group’s secretary general, Hassan Nasrallah, now claims that “the danger of the Syrian regime falling has ended.”

“There is a practical Syrian reality that the West should deal with—not with its wishes and dreams, which proved to be false,” added Hezbollah’s deputy leader Naim Qassem in an interview a few days ago. Qassem claims that the West must now choose to either “have an understanding with Assad, to reach a result, or to keep the crisis open with President Assad having the upper hand in running the country.”

The Need for a Settlement

These are big words, but on the ground the situation isn’t quite so rosy for the Hezbollah leaders. All sides are paying copiously in blood and treasure to sustain their role in the war. That includes Hezbollah and Lebanon itself, which is slowly succumbing to the tensions generated by the Syrian war, as well as Hezbollah’s Iranian paymasters, who are not only funding Shia militias and arms deliveries but also stuck with the bill for Assad’s fuel needs.

The Syrian government itself is in awful shape after three years of conflict, now heavily reliant on outside support and unruly sectarian militias. The army seems unable to advance decisively despite having a clear military edge over the insurgents, partly because of a severe lack of manpower due to defections, sectarian polarization, and territorial losses. As things stand, it appears unlikely that Assad could ever muster enough troops and resources to recapture and stabilize the entire country. More likely, he could fortify his hold over “useful Syria”—the coastal areas and the Lebanese border, Damascus, Aleppo, and the major cities of western, southern, and central Syria, including key energy infrastructure—but that won’t end the war.

Today, the most realistic way to restabilize Syria, with or without Assad, is for foreign states to try to gradually impose a series of deals that would draw in enough credible actors on both sides to dampen the fighting and isolate radical holdouts, then try to consolidate this under some form of live-and-let-live political arrangement. The leaders of Hezbollah, itself born out of fifteen years of civil war in Lebanon, must surely realize this. The question is if their Iranian backers do.

An Iranian Peace Plan?

In an article in the Lebanese daily al-Akhbar, the journalist Sami Kleib—who has strong connections to the Assad regime—claims that the meeting between Fahmy and Hassan was in fact part of a broader albeit discreet Egyptian-Iranian dialogue, partly focused on the war in Syria. According to Kleib, Iran has even suggested a political settlement consisting of four points:

- A comprehensive cease-fire at a national level.

- Forming a national unity government consisting of the regime and the internal Syrian opposition.

- Laying the grounds for a new regime by transferring presidential powers to the government whereby the government will enjoy wide-ranging powers in the years to come.

- Preparing for presidential and parliamentary elections.

Kleib writes that the Egyptian side found the plan weak “because the other side might reject it”—and the Egyptians would be right to think so. While points 1, 3, and 4 are virtually identical to what was proposed in the Geneva communiqué of June 2012, which later formed the starting point of the Geneva II conference on peace in Syria, the phrasing of point 2 is a deal breaker.

Who Should Be in a Unity Government?

Alone among the nations involved in Syria’s war, Iran wasn’t admitted to the Geneva II talks earlier this year, largely because the United States objected to Tehran’s refusal to formally endorse the Geneva communiqué.

If Kleib’s article accurately represents the Iranian point of view, the nature of the national unity government would be the main sticking point. The Geneva communiqué states that such a government should be made up of pro- and anti-Assad members appointed by mutual consent at the peace talks. In practice, the United States, Saudi Arabia, and other states have promoted the exile-based National Coalition for Syrian Opposition and Revolutionary Forces as Assad’s key counterpart at the talks, and they have tried (with limited success) to connect rebel groups on the ground to this structure.

Iran wants to restrict participation even further to only include the “internal opposition.” That phrase is typically used to mean the National Coordination Body for Democratic Change, a small unarmed gathering of secular-leftist opposition groups that have allied with the powerful Kurdish militias of the Democratic Union Party, or PYD by its Kurdish acronym. Presumably, Iran would also see the “internal opposition” as including regime cronies like Qadri Jamil, a former member of Assad’s cabinet.

Not a Viable Opposition Leadership

While these groups could definitely serve a useful role in a national unity government, they are currently (with the exception of the PYD) absolutely powerless on the ground. To make things worse, the Syrian government has made a habit of arresting and kidnapping members of the National Coordination Body to keep it in line politically, with not so much as a peep of protest from the Iranian government. As a result, the National Coordination Body has never been able to function as an internal leadership, and it now has zero influence over the armed rebels and street movements with which Assad needs to negotiate if talks are to have any impact on the ground.

For Iran to claim that an internal opposition thus defined could make up the anti-Assad component of a unity government is either dishonest or delusional. It’s not a peace plan; it’s a recipe for continued war. And until Iran and all the other governments currently fanning the flames of war in Syria have accepted that no peace plan can work without a critical mass of armed actors on both sides, Syria’s slow collapse into Somalia-style anarchy will continue.

About the Author

Former Nonresident Fellow, Middle East Program

Aron Lund was a nonresident fellow in the Middle East Program and the author of several reports and books on the Syrian opposition movement.

- Going South in East GhoutaCommentary

- The Jihadi SpiralCommentary

Aron Lund

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Diwan

- Axis of Resistance or Suicide?Commentary

As Iran defends its interests in the region and its regime’s survival, it may push Hezbollah into the abyss.

Michael Young

- U.S. Aims in Iran Extend Beyond Nuclear IssuesCommentary

Because of this, the costs and risks of an attack merit far more public scrutiny than they are receiving.

Nicole Grajewski

- The Jamaa al-Islamiyya at a CrossroadsCommentary

The organization is under U.S. sanctions, caught between a need to change and a refusal to do so.

Mohamad Fawaz

- Iran and the New Geopolitical MomentCommentary

A coalition of states is seeking to avert a U.S. attack, and Israel is in the forefront of their mind.

Michael Young

- Kurdish Nationalism Rears its Head in SyriaCommentary

A recent offensive by Damascus and the Kurds’ abandonment by Arab allies have left a sense of betrayal.

Wladimir van Wilgenburg