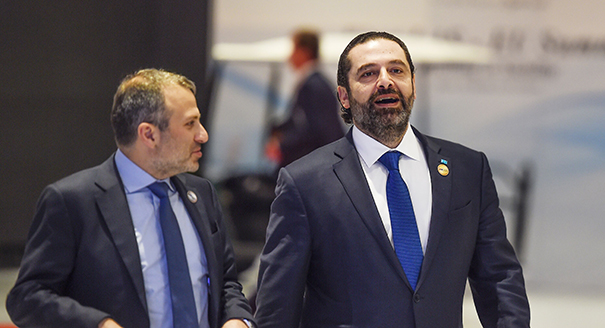

These are not good times for Lebanon’s caretaker prime minister, Sa‘d al-Hariri. In late October he resigned amid street demonstrations against the political class. His unstated intention was to be renamed prime minister of a cabinet he could better control, but the plan collapsed in mid-December when Hassan Diab was tasked with forming a government. Today, Hariri has lost the financial leverage he once enjoyed as well as the support of his political allies and regional backers, and even of many within his own Sunni community.

It’s never wise to write off a Lebanese politician. Some have come back from failure and ignominy to successfully revive their ambitions. Look at President Michel Aoun. However, Hariri would have major hurdles to clear even if Diab failed to form a government and the caretaker prime minister were asked to have a go himself. In tracing Hariri’s decline, three major political errors he made stand out.

The first is Hariri’s departure from Lebanon in 2011 and his absence from the country for over five years. His exit took place not long after his government was brought down by Hezbollah and its allies in January of that year. During his long period away, Hariri’s patronage networks decayed, a situation exacerbated by the financial problems faced by his Saudi Oger contracting company in Saudi Arabia, which had served as his cash cow. For months and even years, many of his Lebanese employees or associates, particularly in his social aid network and media outlets, received no salaries or other payments, and the situation has little improved since.

The collapse of Saudi Oger in July 2017 was a major blow to Hariri. Once one of the largest contracting companies in Saudi Arabia, Saudi Oger had been the jewel in the crown of the late Rafik al-Hariri, Sa‘d’s father. Through a combination of factors, including mismanagement and the Saudi authorities’ failure to reimburse debts owed to the company, Saudi Oger began having difficulties paying employees by late 2015. The crisis soon extended to Hariri’s Lebanese institutions. All this suggested that he had failed to give due priority to preserving the real source of his power—his financial capacities.

Hariri’s disastrous five years away from Lebanon led to his second major error. In attempting to organize a political comeback in 2016, he allied himself with Michel Aoun and his son in law Gebran Bassil, and by extension with Hezbollah. The quid pro quo was a simple one: Hariri would support Aoun’s bid to become president, in exchange for which Aoun and Hezbollah would approve his return to office as prime minister. To persuade his Saudi backers that the deal was worth making, Hariri reportedly assured them that the opening to Aoun would draw the soon-to-be president away from Hezbollah.

What happened was very different. It was immediately apparent to Aoun and Hezbollah that Hariri was without leverage. He was the one who needed them—both to return to office and revive his patronage networks—not them who needed him. This meant that Hariri was much more liable to make concessions to preserve his newborn partnership with the Aounists and Hezbollah than they were. Indeed, Hariri went along with the outrageous demands made by Bassil during the government-formation process, in which Bassil insisted on naming a lion’s share of Christian ministers. By doing so, however, Hariri also angered his traditional Christian ally, the Lebanese Forces Party, which had greatly strengthened its relations with the Saudi regime in the months prior to that.

Very quickly, Hariri looked less like a partner of the Aounists than a façade for the Aounist-Hezbollah alliance, one who bestowed a measure of Sunni legitimacy on the government. This cost Hariri Sunni communal support, adding to the discontent caused by the fact that Hariri’s institutions had still not paid or compensated their many employees who were Sunnis. At the same time, Hariri’s reputation was further damaged by an ambient sense that he had returned to Lebanon to exploit the country’s financial and patronage networks. The ultimate expression of the cynicism toward his motives (and that of others) was the protests of 2019 against the political leadership.

Hariri’s third strategic mistake was that he allowed his relationship with the Saudis to deteriorate to the point where they no longer viewed him as their main representative in Lebanon. This culminated with his apparent sequestration in the kingdom in November 2017, which let to global indignation at the way a sitting prime minister had been humiliated. However, there was a more pernicious outcome from that episode, namely that something had been broken between Hariri and the Saudis. While both sides have preserved a public front of unity, the reality is that Saudi Arabia and the Gulf countries no longer appear to trust Hariri, which has damaged him within his own community. If Hariri is not backed by the region’s leading Sunni power, many Sunnis wonder, what is his value as a communal leader?

The repercussions of this may have been the principal reason why Hariri opted not to form a government in December. His excuse was that the Lebanese Forces would not endorse him in parliamentary consultations to name a prime minister. This would have denied Hariri vital Christian support (as the Aounists had already made clear that they would not back him). That was the official story at least. However, it is more likely that Hariri regarded the Lebanese Forces’ attitude as the result of a Saudi request, or a grasp of Saudi desires. Ignoring it would have further impaired his ties with Riyadh.

When he inherited the political mantle of his father in 2005, Sa‘d al-Hariri had it all: Saudi sponsorship, wealth, and a Sunni community desperately looking for a new leader after the assassination of Rafik al-Hariri. He gradually bought his siblings’ shares in Saudi Oger, gaining the financial means to advance his political agenda. Now, fifteen years later, little is left. Many Lebanese perceive Hariri as being part of the problem of a political class that has lost touch with the population. While functioning in a system dominated by Hezbollah was never going to be easy, Hariri further undermined his situation by making unforced errors that may prove to be fatal politically.