The country’s youthful protest movement is seeking economic improvement, social justice, and just a little hope.

Yasmine Zarhloule

{

"authors": [

"Amr Hamzawy",

"Natalie Triche",

"Sarah Yerkes"

],

"type": "other",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [

"Governance Compared: Democracy and Autocracy in the Global South"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "menaTransitions",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "MEP",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Colombia"

],

"topics": [

"Domestic Politics",

"Civil Society"

]

}

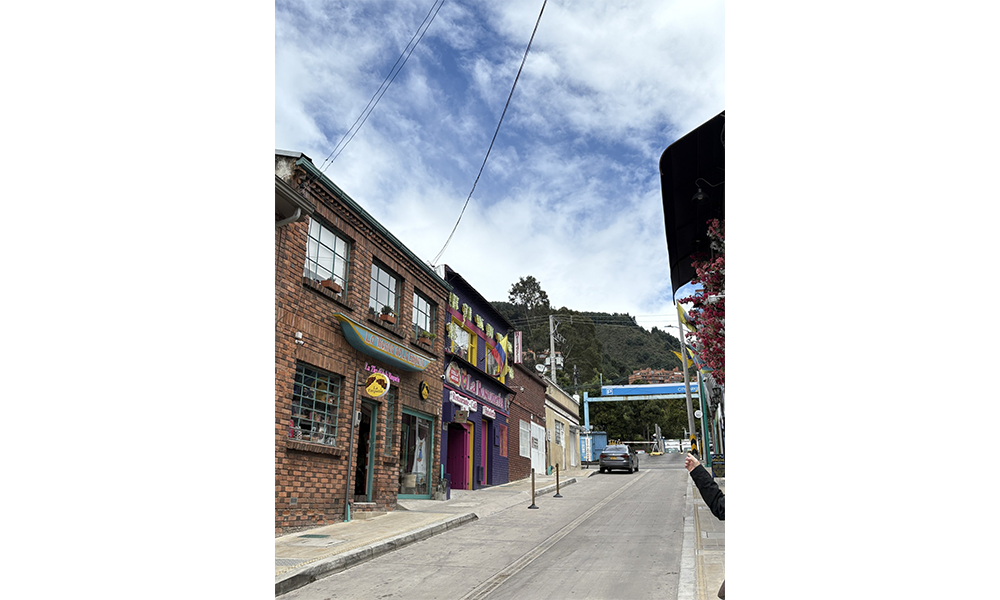

People participate in the so-called Silent March in Bogota on June 15, 2025. (Photo by Raul Arboleda/AFP via Getty Images)

An on-the-ground look at a government at a critical juncture.

In early June, we visited Miami, Florida; Bogotá, Colombia; and Montevideo, Uruguay, to conduct fieldwork for a project, Governance Compared, that critically evaluates the claim that autocracies are more effective at governing than democracies.

In each of four regions of the Global South, we are examining four countries as case studies—two autocratic-leaning and two democratic-leaning. In Latin America, Bolivia and Cuba are the autocratic cases with Bolivia exemplifying higher governance performance than Cuba on social, economic, and cultural needs. On the democratic side, we look at the situation in Uruguay and Colombia, with Uruguay being a high-performing country from a governance perspective, whereas Colombia demonstrates low-performing governance.

For this project, we are defining governance within the context of four buckets. Bucket one is made up of the government’s deliverables felt by the people such as employment and poverty. Bucket two regards access to information. Bucket three evaluates traditional measures of governance including rule of law and extent of corruption. Bucket four assesses civil liberties. In so considering such elements of a government’s performance, we can assess how well the government is providing for their citizens and further assess what form of governance it is embodying.

In this photo essay, we are highlighting the case of Colombia. It has experienced major events in its political landscape this year from assassination attempts to corruption scandals to constitutional crises. It has also retained characteristics of an enduring democracy. It helps show why democracies are uniquely situated to be better at governance.

In Colombia, we encountered a democracy facing a moment of crisis. On June 3, President Gustavo Petro made an unprecedented decision to sidestep constitutionally mandated processes and push his labor reform bill through via popular consultation.

Our focus groups took place the morning after Petro’s announcement, and the issue of labor reforms dominated most of our conversations with policy analysts. Many—on both the right and left side of the political spectrum—expressed concern over the future of democracy in their country. Would the courts be able to stop Petro’s constitutional breach? Are the reforms good? While the latter question garnered confidence from many on the left and rejection from many on the right, opposition to Petro’s challenge to democratic rules of the game and to judicial independence united them.

In meetings with congressional representatives from both the left-of-center Green Party and the right-leaning Democratic Center Party, our focus group participants echoed the same fears of an unprecedented power grab and democratic backsliding. The Green Party representative stated that she supported Petro and his government from his election campaign until the moment he breached the constitutional mandate. She expressed fear that by the next election, Petro would have declared a national emergency, effectively delaying reelection.

During his 2022 campaign, Petro made big promises of reform, especially economic and social reforms tailored to benefit less privileged Colombians, who live in the world’s third most unequal country. As Colombia’s first left-wing president, Petro had plentiful opportunities for reform, and his leftist ideologies diverged greatly from previous decades of right-wing leaders. However, corruption scandals, rising violence, and increasing national debt have left him widely unpopular and greatly struggling to pass the policies on which he campaigned. When Petro took office, his approval rating was 56 percent, but by 2024 it was merely 35 percent.

Petro’s opponents argue that his decree to pass the labor reform legislation by popular consultation is an autocratic move that threatens Colombian democracy. But one of his supporters we spoke with made the case that Congress obstructs the president’s objectives unfairly. The supporter, a researcher at a leftist think tank in Bogotá, views Petro as a strongly democratic leader and noted that “democracy in Colombia means [being] committed to peace.” Latin America has historic association of leftist leaders with autocracy, and some of Petro’s supporters argue that that legacy is harming his image today.

Both sides of the political debate share one belief: governance in Colombia only works for people in urban spaces, and even then, limitedly. For decades, authority in Colombia has come from both state and nonstate actors. Politically motivated armed groups such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) dominate rural areas of the country, as do drug trafficking organizations—and at times, the two work together. In such areas, the national government has little to no capacity to govern. Municipal governments are often weak and rely on financial support from the armed groups and traffickers. Typical government services such as water and sanitation are instead provided by these groups—or not provided at all.

Civil society has attempted to rectify the situation of some rural Colombians who suffer from the proximity to violence and lack of basic services. Bogotá’s La Tienda de la Empatía, for example, sells handmade goods from rural communities in order to boost the incomes of the Wayúu (indigenous) people. The store is run in coordination with the national government and Grupo Aval, a Colombian holding company. In an interview with a representative of a foundation affiliated with a corporation, we were told that many corporations in Colombia have a strong sense of social responsibility and engage extensively in philanthropic activities, which can help to bridge some gaps in governance.

The day after we left Colombia, presidential candidate Miguel Uribe Turbay was shot while speaking at a rally. Political violence in Colombia is rare today, especially in urban spaces, and the shooting was one more bit of evidence for many who feel that Colombia is losing its democracy and that rising political polarization is undermining stability.

Our finding, contrary to the discourse of crisis that we heard repeated, is that Colombia’s democracy is robust and secure. A few weeks after Petro’s labor reform decree, the Council of State—the country’s administrative court—suspended the law, revealing that the power of the judiciary remains intact. Shortly after, the Senate passed Petro’s reform—a rare moment of Congress working with the unpopular president.

On our last day in Bogotá, six participants from opposing political opinions and varying sectors including politics, civil society, development, and academia came together for a passionate conversation about governance in Colombia. Contradictory views flew across the table, as participants were excited to share and defend their perspectives, but the conversation remained respectful. It evidenced engaged citizens who participate in advancing their goals for Colombia through both the government and civil society.

Despite various governance deficits that jeopardize the quality of life in Colombia and the impacts of Petro’s style of contentious and polarizing politics, democracy in Colombia is robust. However, unless governance deficits are addressed and national consensus over peace, freedom, and social justice is re-energized, it will be difficult for Colombians to contain rising violence and keep the democratic rules of the game and institutions stable and legitimate in the eyes of the population.

Director, Middle East Program

Amr Hamzawy is a senior fellow and the director of the Carnegie Middle East Program. His research and writings focus on governance in the Middle East and North Africa, social vulnerability, and the different roles of governments and civil societies in the region.

Natalie Triche

Research Assistant, Middle East Program

Natalie Triche is a research assistant in the Carnegie Middle East Program. She was previously a James C. Gaither Junior Fellow in the Middle East Program.

Senior Fellow, Middle East Program

Sarah Yerkes is a senior fellow in Carnegie’s Middle East Program, where her research focuses on Tunisia’s political, economic, and security developments as well as state-society relations in the Middle East and North Africa.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The country’s youthful protest movement is seeking economic improvement, social justice, and just a little hope.

Yasmine Zarhloule

In fragmented political contexts, climate activism is a way to contest both ecological harm and the structures of violence and neglect that allow it to persist.

Issam Kayssi, Mohanad Hage Ali

Municipal elections in the city may be a harbinger of developments in the Sunni community.

Issam Kayssi

To address the deepening climate crisis, climate activism is employing a wider variety of tactics and aiming at a broader set of goals. In response, the movement faces stronger repression and civic backlash against climate action.

Erin Jones, Richard Youngs

Political calculations on both sides make a ceasefire unlikely.

Yezid Sayigh