The India AI Impact Summit offers a timely opportunity to experiment with and formalize new models of cooperation.

Lakshmee Sharma, Jane Munga

{

"authors": [

"Michael Pettis"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie China"

],

"collections": [

"Carnegie China Commentaries"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie China",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [

"China’s Reform Imperative"

],

"regions": [

"China",

"Japan"

],

"topics": [

"Economy",

"Technology"

]

}

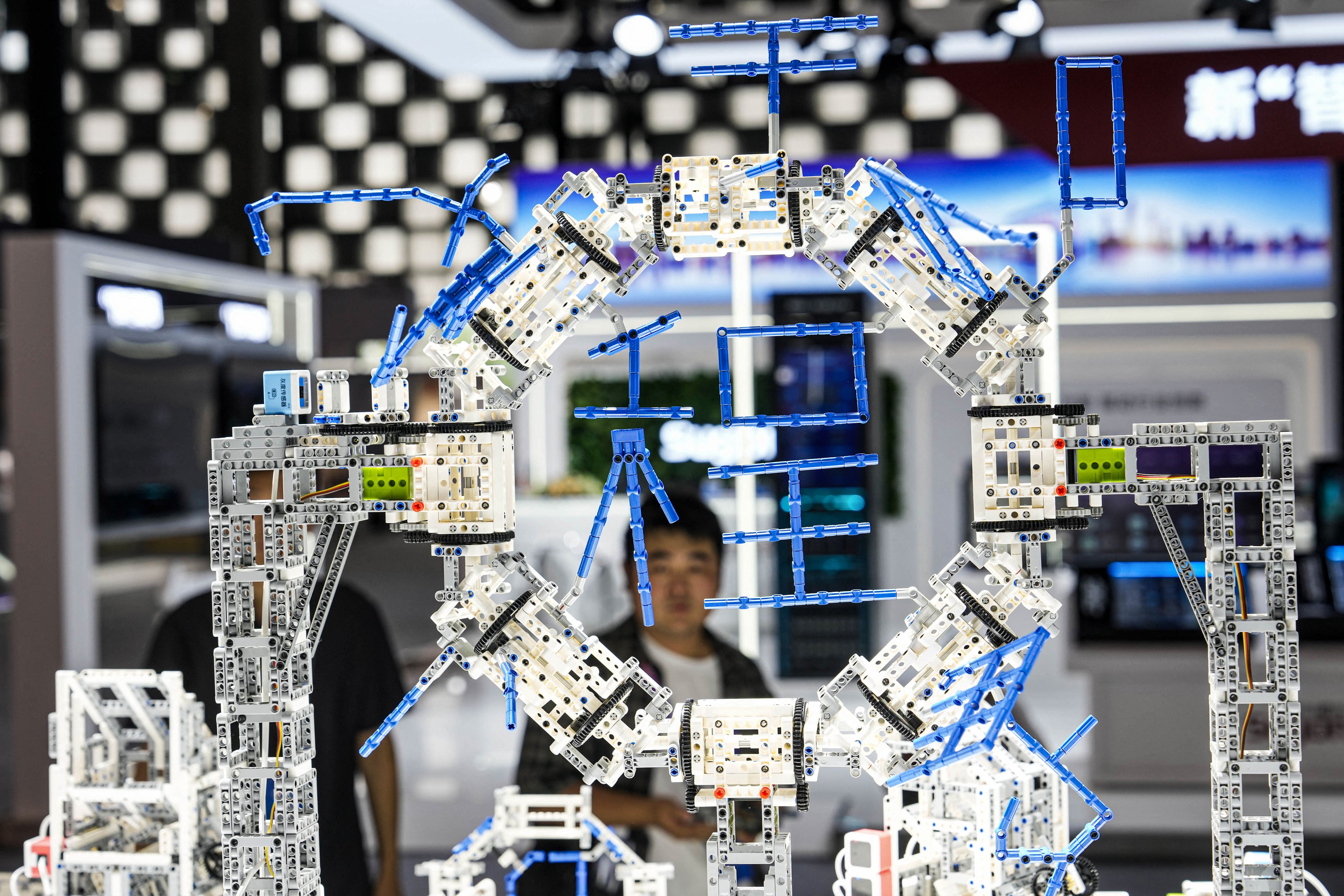

Source: Getty

Ignoring the problems of its historical precedents won’t make China’s success any more likely.

This publication is a product of Carnegie China. For more work by Carnegie China, click here.

If Beijing wants to avoid repeating the long, difficult economic adjustment Japan suffered after 1990, it is important that Chinese policymakers understand what happened in Japan in the 1980s and 1990s and why the country’s adjustment was so difficult.

In recent years, some analysts have argued that China will not repeat Japan’s travails because of Beijing’s focus on developing new technology. Japan, they claim, did little to resolve its problem of weak domestic demand, whereas China will manage it with technological breakthroughs that will boost domestic demand through increases in productivity.

One of the proponents of this view is Lin Yifu, Peking University professor and former chief economist at the World Bank. For example, in a recent interview with the South China Morning Post he said, “Think about it. After the 1980s, which world-leading industries were invented by Japan? Japan’s economic development stagnated because it gave up industrial policy to incubate new industries. But China will not do that, so China will continue to develop.”

This may be wishful thinking. The claim that Japan stagnated because it abandoned an industrial policy designed to develop highly advanced new technologies is hard to square with Japanese history. In fact, most economic historians would argue that Tokyo in the late 1980s and 1990s, like Beijing today, found it politically difficult to address its deep, demand-side imbalances and instead hoped to accelerate supply-side reforms by focusing on the development of new technology.

At the time, Tokyo expected that technological advancement would lead to large enough technological breakthroughs and productivity gains for the overall economy that Japan would be able to rebalance its economy towards a greater role for domestic demand without slowing the growth of the supply side. It would be growth in supply that would drive even faster growth in demand.

In fact, Japan’s technological push was quite successful. It maintained and even expanded its technological lead in many of the most important industries of the 1990s. For example, economist Noah Smith, in response to Lin’s claims, pointed out that in the period after 1990, “Japan created the digital camera industry, 3G, camera phones, the [lithium]-ion battery industry, the hybrid car industry, service robots, and high-performance ceramics.”

Japan’s strategy of expanding industrial policy directed at advanced technology was well-recognized at the time. An April 1986 memorandum prepared by the CIA’s Office of East Asian Analysis, with the title “Attacking Japan’s Saving-Investment Imbalance: Structural Adjustment Versus Fiscal Stimulus,” reported the following: “Despite the nod this week’s Maekawa Commission report gives to structural adjustment [i.e. to policies to expand domestic demand], Tokyo largely sees this concept as a version of industrial policy designed to encourage economic shifts—such as phasing out of depressed industries and development of technologically advanced ones—that will enhance long-run competitiveness.”

The memo noted that rather than implement policies to shift income distribution in favor of raising domestic demand, Tokyo was instead focusing on increasing its international competitiveness by shifting toward what at the time were considered the leading new global technologies (many of which Japan continued to dominate for years).

Five months later, in another memorandum (“Is Tokyo Serious About Boosting Domestic Demand”), the Office of East Asian Analysis noted that the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry “is engaged in an industrial restructuring program designed to phase out uncompetitive segments of the steel and textile industries and to shift the resources to more productive sectors. These moves are designed to enhance international competitiveness rather than encourage firms to focus on the domestic market.” The memo continued: “On balance these steps . . . will probably do more to enhance Japan’s international competitiveness than to reduce its trade surplus. Measures likely to expand domestic spending . . . show little sign of being implemented soon.”

Japan, in other words, did precisely what Lin and others say it didn’t do. What is striking is not that Beijing today is attempting a radically different solution to its economic imbalances than Tokyo’s attempted solution in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but rather how similar its response has so far been to Tokyo’s.

For Japan at the time, while domestic and foreign economists called for measures to expand domestic consumption by directly or indirectly boosting the household income share of gross domestic product (GDP), Tokyo worried that this was the wrong way to address the problem of weak domestic demand. It instead implemented more aggressive supply-side measures designed to boost international competitiveness.

It is perhaps easy to understand why Tokyo chose these measures. Supply-side policies had worked spectacularly well for Japan in the decades after World War II, when its economy was severely underinvested and growth was largely supply constrained. Perhaps because of the difficulty in abandoning a once-successful growth model, Tokyo seemed to think that these policies would continue to work even after the Japanese economy had become severely overinvested and growth had clearly become demand constrained in the early 1980s.

But in the end, supply-side policies failed to drive both rebalancing and rapid growth. The consumption share of Japan’s GDP bottomed out at 63.3 percent in 1991 (compared to 53.4 percent for China in 2022), and it took seventeen years for the consumption share to rise by 10 percentage points. In 2008, it had reached 73.8 percent (still below the global average). During that time, Japan’s share of global GDP dropped from 15 percent to 7.9 percent.

I am not arguing that an intense supply-side focus on developing new technology won’t make a difference for China and will fail. It is certainly possible that such a focus could help China avoid—or at least reduce—a long and difficult adjustment associated with boosting a very weak demand side of the economy. But it is foolish to suggest that such a focus must inevitably work, and even more foolish to claim that China is the first country to try this approach. Many countries have tried to resolve demand imbalances with technology-driven supply-side measures—most notoriously the Soviet Union in the 1960s and Japan in the late 1980s and early 1990s—but it has always proved far more difficult than expected. The important lesson is that ignoring the problems of its historical precedents won’t make China’s success any more likely.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The India AI Impact Summit offers a timely opportunity to experiment with and formalize new models of cooperation.

Lakshmee Sharma, Jane Munga

EU member states clash over how to boost the union’s competitiveness: Some want to favor European industries in public procurement, while others worry this could deter foreign investment. So, can the EU simultaneously attract global capital and reduce dependencies?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

For a real example of political forces engaged in the militarization of society, the Russian leadership might consider looking closer to home.

James D.J. Brown

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum