This publication is a product of Carnegie China. For more work by Carnegie China, click here.

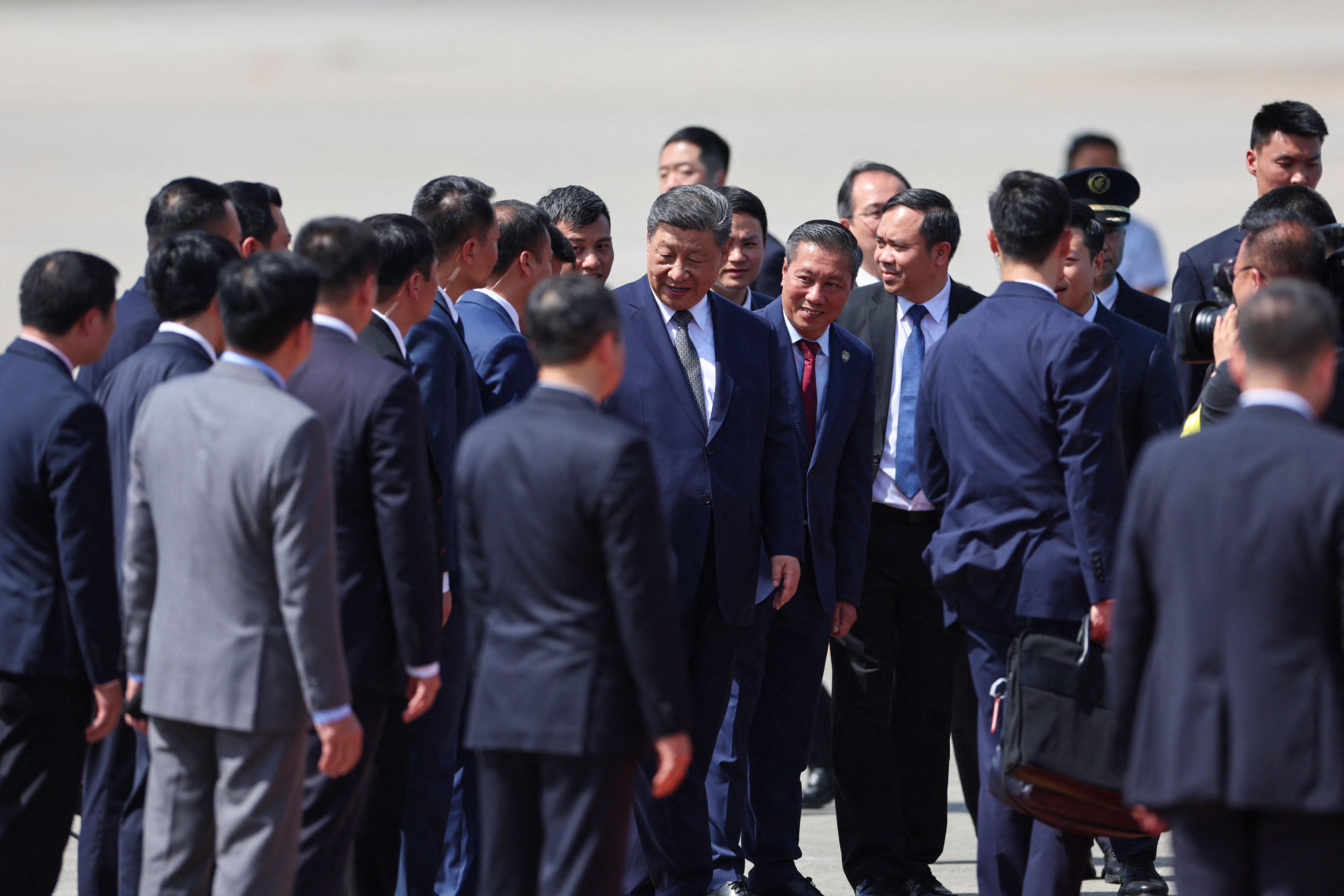

China’s response to the Trump administration’s early actions quickly focused on Southeast Asia. On the eve of Xi Jinping’s visit to Southeast Asia this month, China’s leaders convened a rare Central Conference on Work Related to Neighboring Countries from April 8-9 with a core message: China’s relations with its surrounding countries must now be viewed through a “global perspective” and ties are entering a critical phase of “deep linkage” to broader geopolitical changes. The subtext was clear – China will elevate the prioritization of “neighboring countries” as “major country relations” worsen and strengthen ties in the region as part of its broader response to U.S. trade escalation. Soon after, President Xi departed for a multi-country state visit to Vietnam, Malaysia and Cambodia.

But do countries in the region see their ties in this way or agree with China’s assessment that “China’s relations with its neighboring countries are at their best in modern times?” Security relations between Beijing and South China Sea claimants remain a friction point, trade ties carry both opportunities and major risks, and China’s influence efforts in the region engender suspicion. An April 10 ASEAN ministerial statement triggered by the U.S. tariff decision warned of implications for economic security and stability. Despite the pause in reciprocal tariffs, Singapore Prime Minister Lawrence Wong’s comments captured the post-“Liberation Day” mood – “we are entering a new phase in global affairs… that is more arbitrary, protectionist and dangerous… Because small countries have limited bargaining power in one-on-one bilateral negotiations. So the major powers will dictate the terms, and we risk being marginalized and sidelined.”

Tapping our network of China experts in the region, Carnegie China offers this latest “China Through a Southeast Asian Lens” report to offer preliminary assessments of whether the U.S. effort to reshape the global trading order will lead countries in the region to tilt toward Beijing. We are in the early days of these momentous shifts, and perhaps dealmaking will triumph in some cases over tariffs and U.S. efforts to prioritize Indo-Pacific security will take hold. But the preliminary assessment from our regional experts is that for many, U.S. actions and China’s response will accelerate small country and great power balancing dynamics that were already well underway.

Singapore: No, because China is not the only alternative to the United States.

Singapore is celebrating its 60th National Day this year. As a young nation born during the Cold War, Singapore has benefited from the rules-based order established by the United States and its allies. The peace and stability that prevailed from American power undergirding the international order has allowed Asia to prosper and has protected small states like Singapore. However, American insecurities at home and abroad are leading to protectionist and inward-looking policies that have begun to erode this order. Speaking to the Singapore Parliament, Minister for Foreign Affairs Vivian Balakrishnan warned that the rules-based international order is at risk of degenerating into the “law of the jungle where might makes right.”

Today’s America is not the America Singaporean leaders and policymakers are familiar with. During this year’s Munich Security Conference, Singapore’s Minister for Defense Ng Eng Hen told his audience that Asia’s image of the United States has “changed from liberator to great disruptor to a landlord seeking rent.” Singapore’s leaders and policymakers have come to recognize and accept that the America they knew and admired has changed, and that this change will last beyond Trump. The Biden administration may have been more diplomatic in tone, but it also pursued transactional policies. The United States is now driven by only one interest—to maintain its preeminence at all costs, including costs to friends, allies, and partners.

The United States’ aims are made even more obvious by the Trump administration’s April 2 decision to impose tariffs on the U.S.’s major trading partners. Singapore, which falls into the 10 percent minimum baseline tariff category, imposes no tariffs on U.S. products under the U.S.-Singapore Free Trade Agreement. Trump’s move is even more surprising given that Singapore runs a trade deficit with the United States. Singapore has held off from retaliatory tariffs for now, and Singaporean leaders have urged calm while at the same time preparing the nation for economic setbacks and a dangerous external environment ahead.

But is China the only alternative to the United States? Singapore has excellent relations with China, but it will continue to engage with the United States, welcome all major powers to the region, and diversify its partners. The United States and China are not the only choices Singapore has. As FM Balakrishnan puts it, “We cannot be bullied or bought…It is a big advantage for Singapore not to have to beg for aid. We have no need for assistance or loans that will subject us to pressure…We are not dependent on any single external partner.” In addition to working with middle powers such as Japan, India, Europe, and Australia, Singapore prioritizes strengthening the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as a bulwark against dominance by one single actor. It is also expanding its network of trade partners to Africa and Latin America.

Simultaneously, Singapore is adjusting to the power transition in Asia. As the Trump administration continues to alienate Southeast Asian countries with its trade and foreign policies in the Middle East and Europe, as well as actions that undermine multilateralism, China is stepping into the space it has vacated. While Singapore’s adjustment to a smaller America and a bigger China in the region will be difficult, given deep security and economic ties with the former, such adjustments will not be insurmountable or overly painful. This is because Singapore has strong historical, economic, and cultural linkages with China and has worked assiduously to cultivate ties with Chinese leaders. It is preparing for the long haul, calibrating its policies and bracing its people for a more capricious external environment. To ensure a resilient ASEAN, Singapore will also need to work with ASEAN countries that are close U.S. allies, or that have territorial disputes with China to adjust to a diminished U.S. presence in the region.

Selina Ho

Associate Professor in International Affairs and Co-Director, Centre on Asia and Globalization

Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy

National University of Singapore

Myanmar: Yes, Trump’s policies will pave the way for Beijing’s diplomatic leadership in Myanmar.

For decades, China has been the most dominant external power in Myanmar. While the Obama administration’s Rebalance strategy briefly enabled Myanmar to reduce its dependence on Beijing, it essentially failed to alter Beijing’s deep-rooted influence. China’s embedded economic and geopolitical leverage, as well as Myanmar’s domestic politics, ensured Beijing’s strong foothold in the country. Under these circumstances, Myanmar’s close connection with China is the outcome of a long-term phenomenon. Nevertheless, the United States’ recent adoption of an inward-looking foreign policy under the Trump administration will pave the way for Beijing’s diplomatic leadership in Myanmar.

The 2021 military coup and ongoing political crisis in Myanmar have pushed the country closer to China. Faced with widespread domestic opposition and international isolation, Myanmar’s State Administration Council (SAC) increasingly looks to China for diplomatic support, military hardware and ammunition, economic investments, and development assistance. As Myanmar’s military struggles to maintain much of its territorial control, including losing major cities with regional military command centers to the Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs), China has stepped up its influence on the EAOs to pressure them to negotiate ceasefires. In return for China’s support, the junta pushed for multiple projects under the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, such as the Kyaukphyu deep seaport and other projects that grant China access to the Indian Ocean. Furthermore, China’s security presence in Myanmar is likely to increase as the military junta also legalizes China’s private security presence in Myanmar to protect its investments.

While close relations with China were a matter of necessity for successive governments, public sentiment has long been Beijing’s kryptonite in Myanmar. Despite China’s growing soft power initiative and public diplomacy campaign to improve its image in Myanmar, surveys indicate that Myanmar’s policy elites remain skeptical of China’s intentions. Instead, the surveys show a relatively more positive view of the United States in many aspects. In fact, it is arguably the most valuable form of U.S. influence in Myanmar, given the non-existent economic and security linkage between the two countries. However, President Trump appears to underestimate Myanmar’s geopolitical importance and the role of the U.S. soft power mechanism. By dismantling humanitarian aid and democracy assistance programs, the U.S. is undermining its strategic advantage over China. The need for international humanitarian aid in Myanmar is expected to grow significantly following the devastation of the earthquake that hit the hub of Myanmar on March 28, 2025. The disaster has so far resulted in thousands of casualties and has disrupted access to essential services, such as shelter, electricity, and clean water, for millions of people. The absence of the aid from USAID is likely to limit the effectiveness of the U.S.’s response. In contrast, China has positioned itself as the first country to deploy a disaster relief team to Myanmar and emerged as the largest donor thus far.

Indeed, dealing with Myanmar is also not an easy task for Beijing. China’s support for the State Administrative Council will face legitimacy constraints unless it respects the aspirations of the people. Whether China is willing or able to engage with all parties, including the National Unity Government (NUG), to find a negotiated political outcome will be a key challenge. However, albeit motivated by self-interests, Beijing appears to recognize that “power” is not just about possessing material resources but about presence, engagement, and the ability to offer a compelling alternative. Concurrently, the retreat of the United States is likely to leave societal actors in Myanmar more vulnerable and susceptible to the influence of Beijing.

Khin Khin Kyaw Kyee

Doctoral Candidate

Department of Politics and International Studies

SOAS, University of London

Philippines: No, because of the long-term U.S.-Philippines alliance.

Trump’s transactional approach reflects a more self-interested U.S. foreign policy. This approach will not only strain relationships with allies, but it also signals a shift in the United States’ role from being a stabilizing force to an unreliable partner. As exemplified by his handling of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, recent developments are concerning and have significant implications for Southeast Asia, particularly for the Philippines. The question remains: if Washington can withhold support for Kyiv, what is stopping it from doing the same to Manila in the event of an escalation in the South China Sea?

The Philippines maintains strong security ties with the United States, highlighted by the Mutual Defense Treaty. Under the previous Philippine administration, Manila aimed to balance relations with both Beijing and Washington, seeking to benefit from China’s economic influence while ensuring U.S. security commitments. However, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. abandoned the strategy and prioritized U.S.-Philippine security cooperation due to ongoing clashes with China in the South China Sea.

Through the Biden administration, the United States strengthened security support for the Philippines by expanding the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Arrangement (EDCA) sites, conducting joint military exercises, and deploying the Typhon missile system. This expansion enhances the Philippines’ defense against China and provides the United States with a strategic staging ground if conflict arises between Beijing and Taipei. In 2024, the United States announced its commitment to provide the Philippines with $500 million in military aid. This funding remains secure and has, so far, been spared from the cuts imposed by the Trump administration. This offers the Philippines some reassurance for the time being. U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth’s visit to Manila in March 2025 aimed to reassure the Philippines of Washington’s reliability as security partner.

Nonetheless, U.S.-Philippine security cooperation will be fragile under Donald Trump. The recent imposition of Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs adds another layer of uncertainty to U.S.-Philippine relations, situating the latter in a precarious position as they navigate economic pressures. Manila’s envoy to the U.S., Jose Manuel Romualdez, cautioned that while the partnership may be robust today, it could change tomorrow. He emphasized that the Philippines “must be prepared to defend itself in the future.”

Despite shifts in Washington’s priorities, this is unlikely to bring the Philippines closer to China in the short term. Manila’s rapprochement with Beijing under the previous Duterte administration can only be understood as an exception. The Philippines remains reluctant to embrace a Sino-centric regional order, notwithstanding China’s attempts to exert normative influence in Southeast Asia. A long tradition of U.S.-Philippines alliance has cultivated a strong reservoir of institutional support within the Philippine state in favor of the United States. As a result, the Philippines is likely to continue accommodating the United States under Donald Trump’s administration to maintain its support. The Philippines will also examine the potential roles of allies such as Japan and Australia in serving as strategic buffers against any potential shifts in U.S.-Philippine security relations.

Joseph Ching Velasco

Associate Professor and Vice Chair, Department of Political Science and Development Studies

De La Salle University

Cambodia: No, because Cambodia maintains strategic hedging.

While Trump’s policies create conditions that enhance China’s appeal, Cambodia’s strategic hedging—through engagement with middle powers and leveraging ASEAN as a shield—demonstrates a deliberate effort to maintain balance, making its alignment less of a clear tilt toward China and more of a pragmatic navigation of great power competition.

Trump’s trade policies, particularly those related to the U.S.-China trade war, have indirectly strengthened Cambodia’s economic ties with China. U.S. tariffs have driven major Chinese companies to relocate to Cambodia’s Special Economic Zones, where they now own over half of the country’s factories, representing $9 billion in investments. This has boosted Cambodian exports to the U.S. from $3 billion in 2016 to $13 billion in 2024, nearly 30 percent of its GDP. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects, such as the Phnom Penh-Sihanoukville Expressway and the new Siem Reap International Airport, have further supported infrastructure development by reducing travel time and enhancing tourism. Chinese recent upgrades to Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base also signals Beijing’s aims to de-risking supply chains. However, this economic engagement does not necessarily signal a definitive tilt toward China. Cambodia’s continued export growth also benefits its trade with the United States, suggesting a diversification of economic partners rather than exclusive reliance on Beijing, despite U.S.’ efforts to reshape the global trading system.

Under Prime Minister Hun Manet, Cambodia has maintained a strong partnership with China, as evidenced by his first official visit to Beijing in 2023 and the visit by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, which reaffirmed a commitment to a “high-quality, high-standard community with a shared future” through a second action plan. China’s economic support, with figures from the Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC) showing that the total foreign direct investment (FDI) from China amounted to $34.25 billion or almost 50 percent by January 2025, aligns with Cambodia’s development goals. Yet, this relationship is rooted in pragmatism rather than a strategic pivot. Cambodia also supports China’s global initiatives like the BRI, Global Security Initiative (GSI), and Global Development Initiative (GDI); but this reflects a broader strategy of aligning with partners that meet its immediate needs, not an exclusive alignment with Beijing. Historical ties and geographical proximity play a role, but Cambodia’s foreign policy, as articulated in its 2025 review, emphasizes independence and non-alignment.

Trump’s transactional approach, focusing on short-term gains over long-term alliances, introduces uncertainty for Cambodia. The ninety-day suspension of USAID programs in early 2025 and potential tariffs on China-linked supply chains threaten Cambodia’s dollarized economy. U.S. demands for Cambodia to distance itself from China, coupled with criticism of its human rights record, as seen in the 2022 Cambodia Democracy and Human Rights Act, will create friction. Cambodia seeks pragmatic U.S. cooperation in trade, digital innovation, and maritime security, but Trump’s emphasis on countering China through security partnerships rather than economic incentives limits its appeal. This uncertainty encourages Cambodia to maintain open channels with China, but it does not necessarily equate to a full tilt, as Cambodia continues to explore other partnerships.

Cambodia will continue to employ a robust hedging strategy to navigate great power rivalry, engaging middle powers and leveraging ASEAN to maintain balance. It has deepened ties with Japan and Australia, permitting the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force access to the Ream Naval Base that is deeply associated with China’s regional military ambitions and benefiting from Australia’s contributions to education and security, such as its role in the 1991 Paris Peace Agreements. These relationships offer Cambodia alternatives to superpower dominance, reducing the risk of overreliance on any single partner. Historical lessons, such as the destabilization during the 1970s due to great power entanglements, underscore the importance of this diversification.

Additionally, Cambodia uses ASEAN as a shield, emphasizing multilateralism and neutrality. The 2025 foreign policy review highlights ASEAN centrality as a priority, aiming to support peaceful conflict resolution and realize the ASEAN Community Vision 2045. Through ASEAN, Cambodia engages multiple partners, fostering stability and minimizing vulnerability to U.S.-China pressures, as seen in Ukraine’s proxy role in great power conflicts. This regional platform allows Cambodia to maintain flexibility, ensuring it does not fully align with any single power.

Trump’s approach creates conditions that enhance China’s appeal to Cambodia through economic opportunities and diplomatic reliability, while uncertainty in the United States under Trump 2.0 may strain bilateral ties. However, Cambodia’s strategic hedging—engaging middle powers like Japan and Australia and leveraging ASEAN as a multilateral shield—ensures it maintains balance rather than fully tilting toward China. The sheer size of Chinese investment and BRI projects is significant, but Cambodia’s export growth to the United States and diversified partnerships suggest a nuanced strategy. The recent “Liberation Day” tariffs announced on April 2, 2025, that impose a 49 percent tariff on Cambodian goods—the highest rate in Southeast Asia—could further strain U.S.-Cambodia relations and push Cambodia closer to China, especially as Xi Jinping’s mid-April state visit may capitalize on this economic fallout to deepen ties. In response, Prime Minister Hun Manet has proposed a significant tariff reduction on U.S. goods in 19 categories, dropping from a maximum 35 percent bound rate to a 5 percent applied rate, signaling a willingness to negotiate and potentially mitigating the impact of Trump’s tariffs on Cambodia’s economy while preserving its hedging strategy. For Southeast Asia, these dynamics underscore the importance of pragmatic U.S. engagement to counter China’s influence. Cambodia’s trajectory reflects a careful navigation of great power rivalry, prioritizing flexibility and national interests over a definitive alignment with China.

Neak Chandarith

Director, Institute for International Studies and Public Policy

Royal University of Phnom Penh

Thailand: Trump is not causing Thailand’s shift toward China but accelerating it.

Thailand’s pivot toward China began long before Trump 2.0. For decades, Bangkok has been a credible partner to the West, but its economic and strategic ties with Beijing have steadily deepened since the early twenty-first century. This shift accelerated after the 2014 coup, when Thailand’s military government found itself sidelined by the West. Even after returning to civilian rule in 2023, Bangkok has remained committed to strengthening its relationship with China, joining BRICS as a partner country in 2024.

Yet the civilian government’s foreign policy direction still differs from that of the military government in keyways. While the ties with Beijing continue, Bangkok has also worked to restore the country’s traditional balancing act by rekindling relationships with the West. Thailand has actively participated in the Asia-Pacific Economic Organization (APEC), sought U.S. investment, and joined the U.S.-organized Summit for Democracy. In 2024, Thailand applied for Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) membership, and in 2025, it signed a free trade agreement (FTA) with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) while aiming to finalize an FTA with the EU.

But with Trump back in the White House, maintaining this diversification may become harder. There are already signs that Thailand is leaning further into China’s orbit. In February, Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra met with Xi Jinping to reaffirm commitments to economic and security cooperation. Beyond trade and investment, Bangkok is now turning to China for help in tackling transnational crime, particularly call center scams based in Myanmar’s border towns—an issue largely overlooked by the West.

The bigger question is how Trump’s return will reshape Thailand’s strategic calculus. Even without him, Thailand’s economic ties with China would continue to expand. But his transactional and isolationist approach to foreign policy may embolden Thai policymakers to act in ways they previously hesitated to. If Washington prioritizes interests over values, Bangkok may feel less constrained about moving openly closer to Beijing or in making decisions that deviate from liberal norms.

A stark example of this shift was Thailand’s recent decision to deport at least forty Uyghur men to China after a decade in detention. Why now? Bangkok may have secured something from Beijing in exchange, but more importantly, policymakers likely calculated that such an action would not provoke a strong response from Washington—now more transactional and less committed to human rights. Thailand probably gambled that the fallout (which turned out to be visa sanctions on unnamed officials) could be managed by appealing to American strategic interests elsewhere.

Although the recent U.S. tariffs alarmed the Thai government, Thailand has refrained from broad tariff cuts to appease the Trump administration. Instead, it plans to offer targeted reductions on specific goods and crack down on transshipment, signaling it still sees room to negotiate with Washington from a position of leverage.

In sum, Trump is not causing Thailand’s shift toward China but accelerating a preexisting trend. If the Western-led liberal order continues to fade, Thailand may seek to position itself early in a China-led system. That does not mean it will stop engaging with other partners—it will. The question is whether it can leverage those ties to be seen by Beijing not as a subordinate but as a strategic partner.

Pongkwan Sawasdipakdi

Lecturer, Department of International Affairs, Faculty of Political Science

Thammasat University

Malaysia: Likely, although remains committed to its long-standing non-aligned position.

One of the key variables influencing Malaysia’s foreign policy in 2025 is its ASEAN chairmanship. Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim believes that the chairmanship will provide an opportunity for the country to showcase its leadership in regional affairs and strengthen ASEAN cohesion in tackling various challenges. It will also be a platform for Anwar to engage with external partners, major powers, and regional blocs, such as the Gulf Cooperation Council. The list of foreign leaders traveling to Malaysia will be a long one, including Chinese President Xi Jinping’s mid-April state visit.

But the Trump administration is generally perceived as disinterested in regional multilateral institutions such as ASEAN. President Trump’s well-known proclivity is to engage countries bilaterally to extract the best “deals” and to dismiss regional organizations as irrelevant. While his Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, will have a somewhat greater appreciation of regional bodies like ASEAN, overall Malaysia does not have much expectation for the Trump administration in building up the U.S.-ASEAN partnership. China will be keen to portray itself in clear contrast, a supportive partner of Malaysia during its ASEAN chairmanship, especially with the recent conclusion of the upgrade of the China-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement. Such trade deals will sharply position China as a more reliable partner for trade-reliant countries like Malaysia, as compared to the United States under the second Trump administration, which is willing to impose heavy tariffs even on its close allies and partners. After the April 2 “Liberation Day” announcement by President Trump, Malaysian exports to the United States, with some exempted categories, will face 24 percent tariffs. Malaysia has decided not to impose retaliatory tariffs for now, but these tariffs will also reinforce the determination of the Anwar government to build up economic relations with other partners, such as China, Japan, India, and others.

When Trump was inaugurated in January 2025, Anwar sent him congratulatory remarks and expressed goodwill, but otherwise there has been very little contact between the two leaders. In many ways, Trump’s worldview and policies are antithetical to Anwar’s, especially on issues concerning the Israel-Palestine conflict. On the other hand, even prior to the state visit Anwar has met with both Xi Jinping and Premier Li Qiang, the latter about four times, and has built a comfortable personal-level rapport with these leaders. While these personal-level exchanges do not always directly determine policy, they certainly can foster opportunities and strengthen bilateral ties.

In light of the above developments, China stands to make steady diplomatic gains in Malaysia. As of now, China appears to be a more stable and predictable partner compared to the United States under the Trump administration. Malaysia certainly values a genuine and constructive partnership with the United States but finds the Trump administration capricious and unreliable. It is now anxiously waiting to see if and when the Trump administration will start to impose costly demands on Malaysia. If the Trump administration continues to ignore the damaging consequences of its disruptive policies, Malaysia will likely become closer to China, albeit still within a non-aligned framework.

Ngeow Chow Bing

Non-resident scholar, Carnegie China

Vietnam: No, Vietnam will likely adapt to Trump 2.0 while preserving its multifaceted partnerships.

On April 2, 2025, President Donald Trump imposed a 46 percent reciprocal tariff on Vietnam’s exports to the United States, effective April 9. While now suspended, this steep duty, one of the highest in Trump’s tariff regime, threatens to cause extensive damage to Vietnam’s export-driven economy unless averted by a trade agreement. While this economic pressure might suggest a pivot toward China, Vietnam’s strategic instincts and historical context indicate a more nuanced response: Hanoi will nonetheless strive to maintain balance between Washington and Beijing rather than quickly leaning towards its northern neighbor.

Vietnam’s foreign policy has long been defined by a careful balancing act, cultivating robust ties with both the U.S. and China, alongside powers like Russia, Japan, India, and the European Union. This diversified approach prioritizes autonomy and resilience, avoiding over-dependence on any single nation. Tilting heavily toward China at the expense of the U.S. would jeopardize this strategy, particularly given Vietnam’s fraught history with Beijing. Different efforts by Vietnam, including committing to buy more American products, facilitating U.S. investment, cutting tariffs on various American goods, and top leaders reaching out to Trump diplomatically, reflect Hanoi’s commitment to sustaining ties with the U.S.

Deep-seated mistrust of China, especially over the South China Sea, further anchors Vietnam’s reluctance to drift into China’s orbit. China’s expansive claims and militarization of this vital waterway directly challenge Vietnam’s sovereignty and maritime interests, with tensions flaring over fishing rights and oil exploration. Hanoi relies on U.S. military and diplomatic support to counterbalance Beijing’s assertiveness. Trump’s transactional tariff stance frustrates Vietnam, but the strategic imperative of U.S. backing outweighs immediate economic pain. Losing this counterweight would embolden China, a risk Vietnam is unwilling to take despite the sting of a 46 percent tariff rate.

As such, in the short to medium term, Vietnam is unlikely to lean decisively toward China. Instead, Hanoi will double down on diplomacy, as seen in General Secretary To Lam’s phone call with President Trump on April 4, in which he showed a willingness to eliminate tariffs on American products. Vietnam will also address Trump’s concerns—particularly trade deficits and Chinese transshipment—by tightening origin controls and boosting U.S. imports. This pragmatic approach aims to reduce the tariff and preserve ties with the United States.

However, if the tariff persists and cripples Vietnam’s economic growth, Hanoi may attempt to lessen its trade reliance with the United States, while deepening economic links with China and other partners. This shift, while pragmatic, would erode Vietnam’s balanced foreign policy and autonomy, inadvertently strengthening China’s regional hand.

In sum, facing Trump’s tariff gambit, Vietnam’s preference remains clear: negotiate with Washington while not leaning decisively toward Beijing. Yet, sustained tariffs could force a recalibration, potentially nudging Hanoi toward Beijing, especially in the economic domain. This will weaken U.S. strategic leverage in the Asia-Pacific and hurt its paramount goal of containing China’s rise.

Le Hong Hiep

Senior Fellow and Coordinator, Vietnam Studies Program

ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute

Laos: No, because Laos pursues a careful balance of power.

Under Donald Trump’s current leadership, U.S. foreign policy has adopted an “America first” stance that emphasizes nationalistic trade policies, anti-war military posturing, and disengagement in multilateral cooperation. These policies have significant implications for Southeast Asia, including Laos. However, while Trump’s approach may increase Laos’ engagement with China, it will not fundamentally alter Laos’ relations with China or the United States. This is because Laos has always navigated shifting geopolitical realities and pursued a foreign policy of neutrality (though left-leaning) and a careful balance of power; sympathizing with traditional friends (Vietnam, China, Russia, and Cambodia) while being friendly with its neighbors (Thailand and other ASEAN countries), as well as key powers and partners (the United States, Japan, Australia, India, and European nations) while avoiding superpower conflicts.

Laos’ geography makes it of special interest for the great powers, past and present. During the Cold War, Laos was a key battleground between the United States, the Soviet Union, and China. Laos was not always aligned with China; however, especially during the Sino-Soviet split and China’s military action against Vietnam in 1979, following Vietnam’s deinstallation of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. As for relations with the United States, despite being “the most bombed country on earth” courtesy of America during the Vietnam War, Laos never severed diplomatic ties with the United States. When the Cold War wound down, Laos prioritized improving ties with China (its giant neighbor up north) as well as with the United States (the remaining superpower) and others.

Today, on the economic front, China outperforms the United States on trade and investments in Laos. Laos’ trade with China accounted for $8.23 billion in 2024, making China one of the country’s top trade partners. China exported ($3.68 billion) machinery, electronics, and consumer goods to Laos, while Laos exported ($4.56 billion) agricultural products (bananas, rubbers, casavas), minerals, and natural resources to China. China’s investment in Laos has also been substantial, as much as $10 billion in 2021 and fluctuating between $1 to $2 billion in 2023 to 2024, particularly in mining, hydropower, and infrastructure development (for example, the flagship Laos-China Railway under BRI). Despite high levels of investment and trade with China, Laos has significant commercial relationships with two other countries in the region, especially Thailand ($8.5 billion) and Vietnam ($2 billion). While U.S.-Laos trade is smaller, it is a growing sector of the relationship, and the United States is becoming an important market for Laos exports, such as coffee and garments. The total volume of two-way trade stands at $844 million, with a U.S. trade deficit of $763 million in 2024. Despite being a small country, Trump has gone after Laos with a significant 48 percent tariff rate. These tariffs, pitched as “reciprocal,” were calculated nonsensically. It remains to be seen what the next moves are, but ASEAN, a 670 million population market and the fifth largest global economy, should negotiate as a bloc. Otherwise, ASEAN risks leaving smaller economies behind like Laos, and could further create divisions within the economic bloc. In contrast, China has a zero-tariff policy with Laos since December 2024, promising a further increase in Laos exports to China.

While Trump’s anti-war rhetoric around his administration’s efforts to end the wars in Gaza and Ukraine has been derided as insincere, “transactional,” a “reversal of core U.S. policy,” and “an abandonment of democratic values” by his opponents at home and traditional American allies abroad, it has been quietly appreciated by Laos and other likeminded countries who know all too well the impacts of American-led military (mis)adventures globally for the past eighty years. While Trump’s America First policy may lead to Europe rearming, his non-commitment to defend Taiwan (compared to Biden’s pledge to defend Taiwan while being ambiguous about Taiwanese independence) and perhaps the Philippines in the case of a conflict with China in the South China Sea has the potential to lessen the risks of conflict in Asia’s two hotspots.

The United States has traditionally been a strong leader in supporting and using multilateral cooperation initiatives in the region such as ASEAN and the Mekong River Commission (MRC) to advance regional stability (for example, managing the influence of China, including its Mekong-Lancang Cooperation mechanism), economic integration, and sustainable development, all previously seen as American interests. As an active member of both ASEAN and MRC, Laos sees these platforms as key to its regional diplomacy and leadership in the region. Thus, Laos is anxious about Trump’s narrow view of American interests. During Trump’s first term, Trump had little engagement with ASEAN (he skipped most ASEAN summits during his first term), and now, the termination of a USAID grant worth $5 million for the MRC portends a future without serious U.S. multilateral engagement in the region. And while Trump will not necessarily push Laos and others to the Chinese camp, his signals will certainly make these countries recalibrate and seek to increase cooperation with other powers such as Japan, Australia, India, and European nations, as well as China. Laos will especially be interested in working with these nations on water and climate security where the only effective solution is multilateral cooperation.

Anoulak Kittikhoun

Former Chief Executive Officer

Mekong River Commission

Indonesia: Maybe, as China is becoming more important in Indonesia’s strategic thinking.

When Donald Trump speaks, Indonesia listens. But when he continues to speak, Indonesia becomes concerned, as Trump has a great capacity to utilize U.S. military might and global diplomatic leadership to unbalance the world. For now, Indonesia finds itself frustrated witnessing Trump’s unilateral policies in the United Nations (UN), which hampered Indonesia’s efforts, along with other peace-loving nations, to help settle the Palestine-Israeli war, as well as the Ukraine-Russia war.

Witnessing Trump’s eighty-nine executive orders, Indonesia gets the impression that the United States is restructuring its economy and responding to its huge federal debt; thus, reducing its capacity to win global markets. Similarly, Indonesia felt uneasy witnessing Trump’s readiness to raise tariffs on Chinese goods, as similar pressures may also be applied to Indonesia, considering Indonesia’s recent membership in BRICS.

As the natural leader of ASEAN, Indonesia respects China’s unilateral and multilateral capacities to help stabilize the world order via utilizing all kinds of mechanisms under the auspices of the UN and South-South cooperation. Indonesia also admires China’s capacity to utilize the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area and ASEAN-China Comprehensive Strategic Partnership to build mega infrastructure projects in most ASEAN member countries, including Indonesia. For Indonesia in particular, China has become Indonesia’s top export destination, with the United States coming second.

There is a belief inside Indonesia today that the world era of Pax Americana is being replaced by Pax Sinica. Nevertheless, being economically closer to China does not necessarily mean Indonesia is taking a side in the U.S.-China global rivalry, as Indonesia is unilaterally maintaining a comprehensive strategic partnership with both countries. In reality, it is very difficult for Indonesia to be neutral, as the U.S. and China have unilateral capacities to check Indonesian independence with further tariffs and sanctions.

Indonesia’s response is unique. At the economic level, acknowledging ongoing trade and investment, which gives China the upper hand, Indonesia has tried to engage with the U.S., Japan, and EU nations to improve trade and invest inside Indonesia to counter-balance China.

At the strategic level, acknowledging China’s military might and greater confidence in the South China Sea, Indonesia silently permits fellow countries inside ASEAN to continue their defense training and cooperation with the United States. This situation has so far helped prevent escalating tensions in Southeast Asia, even though anxiety surrounding China’s nine-dash line remains. At the same time, Indonesia has provided greater access to the United States to conduct military exercises with Indonesia, manifested in the practice of Super Garuda Shield in 2024, which, in terms of quality and substance, is far beyond Indonesia-China defense cooperation.

At the political level, Indonesia is actively supporting UN peace and development initiatives for a more peaceful world by utilizing its role inside the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and making itself useful as a qualified bridge builder.

In conclusion, even though it is very difficult to be in the middle of the U.S.-China rivalry, China is becoming more important in Indonesia’s strategic thinking.

Teuku Rezasyah

Associate Professor in International Relations

Padjadjaran University and President University