What should happen when sanctions designed to weaken the Belarusian regime end up enriching and strengthening the Kremlin?

Denis Kishinevsky

{

"authors": [

"Peter Kellner"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Europe"

],

"collections": [

"Brexit and UK Politics"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Europe",

"programAffiliation": "EP",

"programs": [

"Europe"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Europe",

"Western Europe",

"United Kingdom",

"Iran"

],

"topics": [

"EU"

]

}

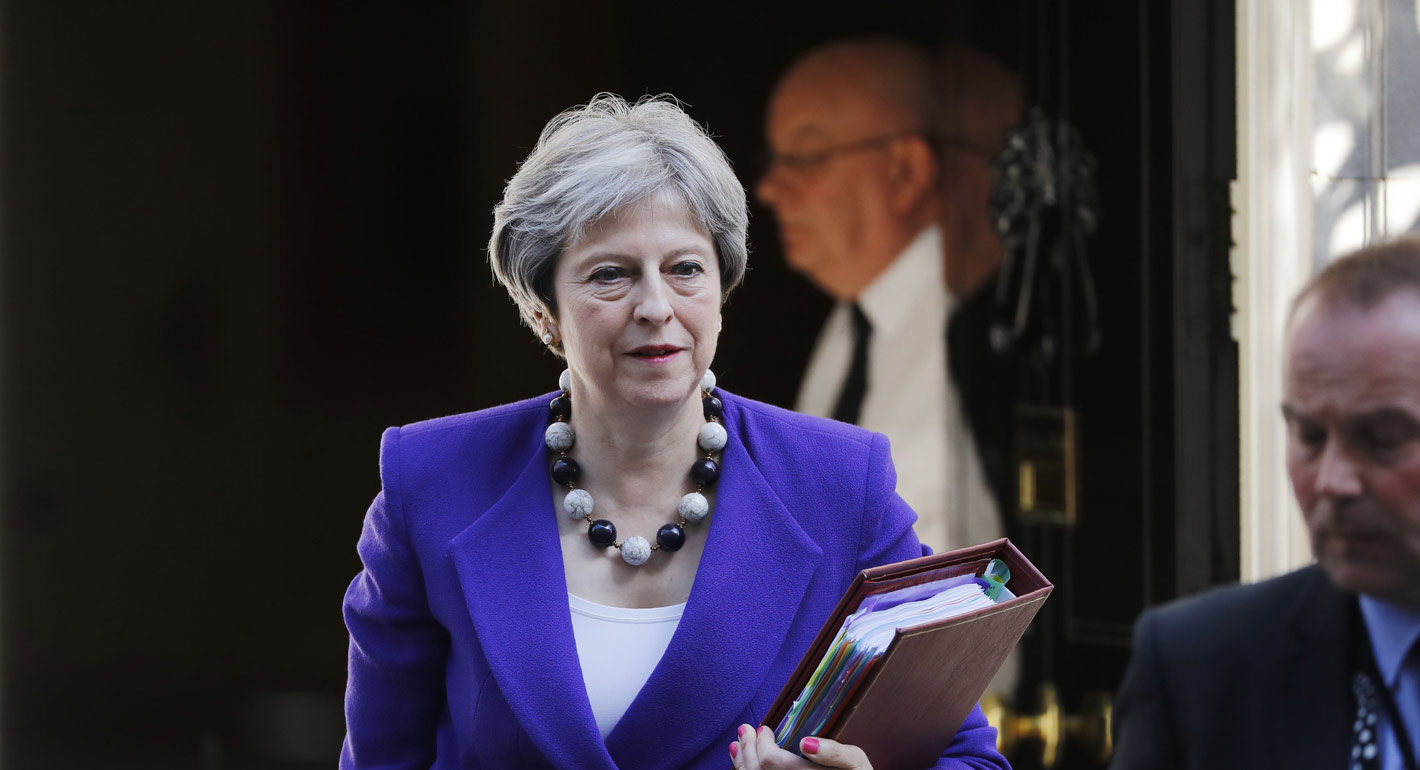

Source: Getty

The United Kingdom looks certain to remain in the EU at least into the summer of 2019—and, very possibly, indefinitely.

Faced with almost certain rejection, U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May delayed a parliamentary vote on Monday on her plans for leaving the EU. To win over MPs, she is now seeking to amend the deal, in particular the complex arrangements concerning the future of the border between the U.K. and Ireland — the only land border between the U.K. and the rest of the EU.

The big picture: EU leaders have made clear that the 585-page withdrawal agreement cannot be changed. All May can expect is a side letter containing a legally meaningless “clarification,” which will satisfy very few, if any, MPs in London. Whenever she calls the vote, she is likely to face a heavy parliamentary defeat.

Background: The U.K. Parliament voted to leave the EU on March 29, 2019. Without a deal, the prospects for the U.K.’s — and, to some extent, the EU’s — economy will darken. The government’s own projection is that a “no deal” Brexit could provoke an economic slump of 10%.

What's next: The pressure to prevent a “no deal” Brexit will be intense. There are several possible paths:

The bottom line: None of the three options can realistically be concluded by March 29. The U.K. looks certain to remain in the EU at least into the summer — and, very possibly, indefinitely.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

What should happen when sanctions designed to weaken the Belarusian regime end up enriching and strengthening the Kremlin?

Denis Kishinevsky

The supposed threats from China and Russia pose far less of a danger to both Greenland and the Arctic than the prospect of an unscrupulous takeover of the island.

Andrei Dagaev

Western negotiators often believe territory is just a bargaining chip when it comes to peace in Ukraine, but Putin is obsessed with empire-building.

Andrey Pertsev

Unexpectedly, Trump’s America appears to have replaced Putin’s Russia’s as the world’s biggest disruptor.

Alexander Baunov

Baku may allow radical nationalists to publicly discuss “reunification” with Azeri Iranians, but the president and key officials prefer not to comment publicly on the protests in Iran.

Bashir Kitachaev