Konark Bhandari

A Tech Policy Planning Guide for India—Beyond the First 100 Days

On June 9, 2024, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi took an oath to lead the new government for a third successive term. Earlier in the year, he had announced his administration’s desire to implement key policy decisions within the first hundred days of the new government, if elected. Since taking office in June 2024, the new government has unveiled a series of ambitious infrastructure and logistics projects, alongside other initiatives. The technology ecosystem has also seen significant developments, in the form of a policy to boost bio-manufacturing as well as the launch of a new venture capital fund for incubating space technology.

Clearly, this has set the tone for the government’s post-election agenda. As the newly elected administration completes its first hundred days in office, a more sustained and farsighted roadmap in the technology sphere will be required. Towards this end, scholars at Carnegie India have put together this compendium of nine chapters with pointed recommendations that the government may consider as it charts the course on a tech-first agenda. In doing so, this compendium also surveys the current landscape of their respective technological areas to arrive at a crisp evaluation of how existing schemes have played out. This is relevant as we approach the ten-year anniversary of Digital India, the current government’s tech-heavy agenda that was launched in 2015. The Carnegie India team has spent months and years tracking these ecosystems and has spoken extensively to stakeholders in government, academia, and the private sector to relay these findings.

On artificial intelligence (AI), an assessment of whether the emerging ecosystem raises novel or unique risks has been suggested. Since the AI domain is heavily driven by private initiative, a recommendation to assess the likelihood of market failure, prior to introducing regulation, has been offered. Similarly, on AI compute, a thorough audit of the existing landscape has been proposed, as the lack of data on how existing compute capacity is being used may handicap future efforts to map demand trends. A crisp summary of the India-U.S. initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET) has also been undertaken, with suggestions about how a new administration in the U.S. government may pose opportunities and challenges for India, with interlocutors on both sides possibly needing to socialize the benefits of the partnership to their respective administrations as well. On the topic of digital competition law, it has been noted that anti-competitive practices have become more prevalent, as evidenced by an increasing number of such cases. What may be needed going forward is the utilization of the existing tools under the current competition law, which have been effective in relaying timely decisions through the competition regulator.

On deep tech, as India seeks to build on the successes of its semiconductor incentive scheme, what may be needed going ahead is to build a resilient supply chain by encouraging the presence of more suppliers, which supply to anchor semiconductor firms. Furthermore, a re-think may be required on tariffs, to ensure that India’s trade policy is an enabler for domestic firms to assemble and produce products cost-effectively and competitively. This compendium also speaks about the growing urgency for a cyber strategy that can build on the twin features of “defensibility” and “resilience,” essentially suggesting that cybersecurity features be baked into the current digital architecture and not necessarily provided as “add-ons.” On biotechnology, India has been increasingly seeking to move up the value chain. However, bottlenecks remain in the form of regulatory delays and sub-optimal coordination mechanisms. Here, India’s success in streamlining regulatory approvals during the COVID-19 pandemic holds lessons that may be worth emulating in the larger biopharmaceutical context. Lastly, on space technology, we have proposed measures that may be undertaken to boost India’s space exports, both by easing supply-side constraints and boosting demand-side drivers.

Overall, the aim of this compendium is to provide an independent look at how to get the most out of India’s current technology ecosystem, and the measures that may need to be adopted or re-considered in order to build a lasting and enduring framework for policy changes in the select areas under the current administration.

About the Author

Fellow, Technology and Society Program

Konark Bhandari is a fellow with Carnegie India.

- India Signs the Pax Silica—A Counter to Pax Sinica?Commentary

- Revisiting the Usage of Refurbished Equipment in India’s Semiconductor EcosystemArticle

Shruti Mittal, Konark Bhandari

Recent Work

The Modi government has introduced numerous reforms over the last ten years, but none as transformative as Digital India.1 The flagship program, launched in July 2015 with the aim to digitally empower India’s citizens, has propelled the nation forward with pioneering programs like Aadhaar, UPI, eSign, and Government e Marketplace.2 These initiatives, marked by near-universal adoption even among its impoverished and low-literate population, have revolutionized India.

The role of government in creating a “tech-first” India is paramount. This digital revolution was spearheaded through the India Stack, an open API-based public IT infrastructure supporting thousands of public and private applications, enabling India to outpace even the most developed countries.3 However, in the rapidly evolving digital landscape, past successes are fleeting. Continuous innovation and adaptability are essential to maintain leadership. In this essay, I will evaluate key programs and initiatives, offering recommendations for policy reforms and institutional changes necessary to harness AI’s potential, fortify cybersecurity, and develop cyber forensics. The discussion will extend to the strategic exploitation of data wealth, navigating digital competition, and the emerging challenges posed by quantum computing. Each section will provide insights into how India can position itself as a global leader in these domains, ensuring sustained innovation and economic growth.

Artificial Intelligence

The IndiaAI Mission, approved in March 2024 with a budget of Rs 10,371 crores (approximately $1.2 billion), marks a significant proactive step in India’s digital journey. It covers extensive ground under its seven pillars: developing a 10,000 graphics processing units (GPU) compute capacity in public-private partnership; development of indigenous domain-specific large multimodal models; the establishment of a unified data platform; funding to industry for the development of AI applications; development of human resource in AI skills; deep tech AI funding to startups; and promoting safe and ethical AI.4

The 10,000 GPUs proposed under the IndiaAI Mission is modest compared to industry leaders like China and the United States, who have aggressively acquired GPUs over the past decade and have ambitious plans for the future. However, India need not mimic their strategy by attempting to match or surpass them in the number of GPUs.5 Instead, it should adopt a smart fast follower’s approach. We outline some features of this approach.

Firstly, empaneling vendors for its 10,000 GPUs would enable the government to establish a high-quality compute facility in a fast, cost-efficient manner and create a bigger market for GPUs. However, potential issues such as continuity, vendor lock-in, and data security and privacy, must be addressed. Secondly, to foster the growth of Indian startups, the government must also ensure that compute infrastructure is accessible to those who cannot afford the current market rates of Rs 100 (approximately $1.20) per GPU hour.6 Subsidies could be a viable way to support emerging startups. Third, the government should prioritize directing compute capacity toward critical sectors such as agriculture, education, healthcare, water, and sanitation, focusing on foundational models.

Fourth, strategic and security domains should also be prioritized to advance sovereign AI development. The need for sovereign AI is also reinforced by the global context—in 2020, the United States launched the Clean Network initiative that targeted Chinese cloud providers, while many European countries have become increasingly skeptical of American cloud services due to surveillance fears.7 This has led to cloud certification schemes that restrict certain providers from serving specific public sector organizations.8 Despite this, compute for AI currently relies heavily on cloud infrastructure dominated by hyperscalers from China and the United States. A study reveals that U.S.-based Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud collectively hold nearly 70 percent of the global public cloud market, with Chinese tech giants Alibaba, Huawei, and Tencent controlling much of the remainder.9

Therefore, to ensure the security of critical data and to minimize reliance on foreign cloud services, it is imperative that the compute infrastructure be physically located within India and operated on an Indian cloud platform. The government could also consider allocating a portion of the envisioned compute infrastructure to a secure, non-cloud environment, specifically built for sensitive or classified applications. Fifth, an autonomous body, led by industry leaders with professional expertise and representatives from the government, should form the management of such a facility, similar to the IN-SPACe model.10 Sixth, India could build on the Open Cloud Compute project to leverage existing large central processing units or compute capacities from conventional computers.11

Seventh, India needs to leverage its domain-specific data strengths. With one of the highest numbers of internet users worldwide, India boasts a vibrant and diverse data landscape, vital for AI model development. By making this dataset available to startups and industry, we can develop context-specific foundational models and AI applications in domains like agriculture, health, education, water, and sanitation for India and the rest of the world. The scalable and open API system of data sharing through the Digital Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) framework for training AI models offers a robust framework to ensure all data flows are consent-based and secure, and should be supported.12 The successful implementation of the account aggregator (AA) system in the financial sector—with 2.12 billion financial accounts enabled to share data on it—should be mirrored in sectors like health, education, and agriculture.13

Eighth, India needs to scale up its AI human resources to capture ten percent of the projected global demand for over 100 million AI jobs worldwide.14 This process will need to be market-based and industry-led since it will involve retraining existing workers alongside millions of others. The growth of the information technology (IT) sector was primarily industry-led. As the demand for skilled human resources grows, industry bodies like the National Association of Software and Service Companies (NASSCOM) can play a crucial role by identifying the level of skilling required for various roles. The creation of training standards and certifications could further encourage the private sector to participate in AI skilling. Boosting the skilling sector would require market-based skilling models and the democratization of AI skilling to STEM colleges beyond engineering colleges, thereby attracting youth in smaller cities and rural areas to AI-related training. NASSCOM could further create standards for certified courses, grounded in an in-depth study of the required skills and strategies to invigorate the skilling segment. The key objective is to create a strong connection between demand, education, and skilling, ensuring that the market’s needs are effectively addressed through targeted education and training initiatives.

Finally, to foster greater trust in AI, forward-thinking legislation is essential. Many countries worldwide are enacting such legislation. The EU’s AI Act exemplifies a rule-based approach to AI, requiring actors to meet specific obligations.15 China Brazil, and Canada follow a similar approach. In contrast, nations like the United Kingdom, Singapore, and Japan have opted for a light-touch principles-based approach that grants developers the freedom to interpret regulations and implement risk mitigation measures as they deem fit.16 Given India’s current awareness of AI governance, a rule-based approach appears suitable. However, crafting effective legislation demands a deep understanding of India’s legal framework. Additionally, the cross-sectoral nature of AI necessitates a broader comprehension of the socio-techno-legal landscape. Therefore, forming a committee, chaired by an eminent retired Supreme Court judge, would be ideal for drafting this legislation. Such leadership could ensure a balanced, impartial approach that addresses the rights and needs at stake.

Cybersecurity

With increased digitization, cyber attacks and cybercrimes have caused significant economic losses and heightened privacy concerns. Modest innovations in cybersecurity struggle to counter threats from emerging domains. Existing public key encryption algorithms, which use a public key for encryption and a private key for decryption—often for verifying digital signatures—are facing significant threats from quantum computing. Meanwhile, hackers are leveraging AI tools to develop new types of cyber attacks. Cryptocurrency-based cybercrime is a growing issue, and drones and automobiles are becoming potential targets. This problem is acute in both public and private sectors, exacerbated by a lack of domain-specific cybersecurity regulations.

Regulations ensure that parties are accountable for lapses and determine penalties for wrongful acts. Currently, only banking, securities exchanges, and market infrastructure entities are subject to such regulations, leaving sectors like oil and gas, maritime, steel, healthcare, education, drones, and automobiles vulnerable. Poor coding standards and a lack of skilled manpower compound the issue. There needs to be a focus on skilling in coding. The Electronics and Information and Communication Technology Academies Programme approved by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) in 2014 was a commendable initiative that sought to train 92,800 faculties from tier-2 and 3 engineering colleges.17 More such programs should be implemented. Again, it is imperative that industry bodies like NASSCOM be involved in formulating such programs to determine demand-oriented skilling standards. Additional review of such standards may be undertaken by the Sector Skill Council.

A new cybersecurity policy is long overdue to replace the 2013 version, not just with revised text but with a forward-looking strategy to tackle today’s vastly different cybersecurity challenges. This policy should guide institutions across the country, particularly those less familiar with cybersecurity threats and solutions. For this, sector-specific regulatory frameworks and supervision for all major sectors, including drones and automobiles, should be developed alongside the promotion of innovation in all emerging areas of cybersecurity. A roadmap for transitioning to post-quantum cryptography (PQC) solutions for critical applications should be established, following the example of the United States’ mandate for federal agencies.18 Cybersecurity-related human resource development is crucial to meet domestic needs and export expertise. MeitY’s skilling initiatives must be scaled up with increased funding and expanded to more training institutes and colleges nationwide, leveraging online skilling platforms as well. Given the increasing demand for cybersecurity professionals across various sectors, not just within IT, it is crucial for MeitY, in collaboration with the Data Security Council of India and the Confederation of Indian Industry, to establish a platform that connects non-IT industry users with trained cybersecurity experts who can effectively address their needs.

Cyber Forensics

In the current digital age, every action on the internet leaves a digital footprint that can be analyzed and investigated. The digital forensics market is growing at 16.3 percent annually.19 In India, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, imposes legal obligations on data fiduciaries, giving a significant boost to this market.20 Despite a robust IT industry, India relies on imported tools and lacks skilled manpower. Few police and investigative agencies are trained in digital forensics—a gap that extends to businesses. While the private sector is expected to lead in the provision of digital forensic services and applications, police forces and relevant government departments will have to be adequately trained to be able to use them to their advantage. It is essential to raise awareness about forensic capabilities and ensure adequate training for police officers. The government should focus on building and expanding infrastructure, following the example of Gujarat’s National Forensic Sciences University, the first of its kind in the country. Additionally, private universities should be encouraged to develop and offer courses in this field. Currently, only government labs can be notified as “Examiner of Electronic Evidence” under the IT Act, 2008.21 The government should notify private labs under Section 79A, implement training for police, prosecutors, and judiciary, and launch startup challenges for forensic tools. MeitY should develop Indian standards for these tools, and the Data Protection Board should create standard operating procedures (SOPs) for digital forensics in vulnerable sectors like banking and pharma.

Exploiting Data Wealth

Tech giants like Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and Amazon have become trillion-dollar enterprises by leveraging data. As one of the largest data producers in the world, India’s data has the potential to significantly contribute to its gross domestic product (GDP) through data monetization models, which will also ensure that individuals benefit from their own data. The AA system empowers users to securely share their financial information with institutions, offering better deals on loans, investments, and more, while maintaining privacy. Progress made within the AA system must be implemented across the economy along with the expedition of the DEPA to enable data monetization in other sectors including health, pharma, and education.

Land and geospatial information can contribute 0.5 percent to annual GDP growth, yet high-quality geospatial data remains scarce in India. The Svamitva scheme which uses drone surveys, faces hurdles that need resolution.22 Recent reforms in the map policy in February 2021 and the new drone policy in August 2021 lay the foundation for improving geospatial data. A critical next step could be the prompt compilation of nationwide geospatial data. The PM GatiShakti, a geographic information system (GIS)-based national master plan, offers great efficiencies in infrastructure investments and should be universalized for all projects.23 A PM Gati Shakti initiative for the underwater domain could leverage the economic benefits of the blue economy by developing smart maritime zones, akin to smart cities, facilitating technology-driven maritime spatial planning. This would ensure the optimal and sustainable exploitation of marine resources and address challenges like safe navigation, search and recovery operations, protection of economic assets, and prevention of underwater pollution.

Moving From “Make in India” to “Make Products in India”

In a tech-driven knowledge economy, a product’s intellectual property (IP) constitutes half or even more of its total value, making it challenging to equalize value-creation through manufacturing alone. This understanding has prompted China to shift its focus from being a global manufacturing hub to aspiring to be the world leader in innovation by 2050. For India to become a “developed” country, it must transition from “Make in India” to “Make Products in India,” avoiding the middle-income trap or the risk of aging before becoming wealthy. Though India excels in IT and information technology-enabled services (ITeS) and is making strides in electronic manufacturing, there is an urgent need to reform policies and incentives to drive product innovation. The focus should be where the real value lies: developing IP and technology, especially in the digital domain, where IP can account for nearly 50 percent or more of the value. Controlling IP not only brings economic benefits but also offers strategic advantages.

Simultaneously, continuing efforts in manufacturing under “Make in India” will be crucial for generating jobs, particularly given the country’s youthful demographic. India’s startup ecosystem provides a solid foundation, but more effort is needed. The mantra should be “ease-of-doing innovation,” prioritizing the merits of innovation over strict adherence to prosaic rules and procedures. Government procurement should promote innovation by acting as a validation for innovators, instilling consumer confidence, and ensuring revenue streams to mitigate risks. The general financial rules (GFR) need to provide a clear framework to properly define and procure indigenously developed products, inter alia, and a mechanism to fix prices.

The government should allocate funding to mitigate risks in product development, particularly in fabless chip design, a cornerstone for digital products. Successful models like the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in the United States and Yozma in Israel can provide valuable insights.24 The Innovations for Defence Excellence (iDEX) model—which creates an ecosystem connecting defense industries, including micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), startups, individual innovators, research and development (R&D) institutes, and academia—should be expanded beyond defense.25 Launched in April 2018 by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, iDEX is a transformative initiative that drove defense innovation through Defence India Startup Challenges (DISC).26 By inviting startups to address the specific needs of the army, navy, and air force, iDEX rapidly produced indigenous technology solutions. With grants up to Rs 1.5 crore (approximately $180,000), startups developed cost-effective, high-quality innovations in twelve to eighteen months, revolutionizing India’s defense R&D landscape. Shifting from previous practices, iDEX allowed startups to retain intellectual property (IP) rights, while the government reserved march-in rights for national interest. This project encouraged startups to explore commercial and export opportunities. In addition to the expansion of the iDEX model, introducing an R&D-focused fund with increased government participation can attract private investment and effectively mitigate risks associated with innovation.

Combining India’s demographic advantage with a sizable talent pool in emerging technologies like AI, quantum computing, and blockchain is crucial. Drawing lessons from Stanford University’s success, academic universities in India must act as hubs for entrepreneurship and innovation. The Startup India initiative has achieved remarkable progress, with numerous universities and colleges nationwide fostering startups through government grants.27 The next crucial step is to expand the venture capital industry and establish connections with these incubators. The recently launched Mounttech Growth Fund focused on defense, space, and deep tech, has forged memorandums of understanding (MoUs) with several college incubators to provide risk funding for technological ventures.28 Additionally, the ability to translate lab research into successful commercial enterprises should become a key metric in evaluating academic faculty. State governments could create a supportive ecosystem by aligning industrial development schemes with incubation activities of universities within their regions.

Building a brand and establishing public trust for indigenously developed products is essential to challenge the dominance of global brands like Intel, Samsung, and Apple. Establishing global recognition for indigenous innovations could be assigned to the Indian Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF).29 A notable example of building trust in homegrown products was witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic when Prime Minister Modi quashed attempts to undermine India’s indigenous vaccine Covaxin, by becoming its first recipient.30 Such public endorsements significantly enhance brand recognition and credibility. Furthermore, as a state policy, the government should actively promote the export of indigenously developed products through bilateral and multilateral channels. Wherever feasible, Indian aid should be tied to the distribution of these native products, boosting their acceptance on the international stage.

The centrality of standards-making to technology development and adoption cannot be overemphasized. Standards help create a unified market, drive economies of scale, and ensure global acceptance of innovations. MeitY’s 2012 Requirements for Compulsory Registration Order was a significant success in enforcing standards by introducing self-registration, replacing the burdensome license-based system.31 This success led to amendments in the Bureau of Indian Standards Act in 2016, mainstreaming self-registration and self-certification. As a result, standard adoption surged from just a handful in 2014 to over 500 by 2023, with expectations of adding nearly 2,000 more soon.32

The initiative to develop new standards for emerging digital technologies should be led by the MeitY. Once India establishes its standards for these new capabilities, methods, or products, the MeitY should also work towards making these standards global. The large Indian market for digital goods and services can help in this effort. The success of the India Stack, which started as a national standard and later became global, should be replicated for future innovations in the sector.” Collaboration between the government and industry is essential to secure decision-making roles in international standard-making bodies. National standard-making institutions across various technological domains could be industry-led, with legislative recognition for such bodies as a preliminary step.

Navigating Digital Competition

Digital products and services often exhibit strong network effects leading to winner-takes-all scenarios, thereby creating monopolies or oligopolies, such as Google Search, Microsoft Office, Android OS, WhatsApp, and Facebook. Digitalization has significantly increased the network economy’s share in GDP, and this trend is expected to keep growing. Addressing competition in the digital domain presents a formidable challenge for governments and regulators. As networks expand and acquire large user bases, their offerings increasingly resemble public goods, though they remain privately controlled, leading to significant policy implications. The Ministry of Corporate Affairs has recommended a draft law with ex-ante control to address emerging challenges—bundling or tying products to existing networks, self-preferencing, preventing third-party products, monopolistic use of data, deep e-commerce discounts, exclusive tie-ups, search and ranking preferences, restricting third-party apps, and anti-competitive advertising policies.33

However, the proposal for ex-ante regulation raises concerns that the regulatory environment may resemble the restrictive license raj and inspector raj, potentially limiting the innovative freedom that has characterized this sector so far. Past experiences show ex-ante regulations often fail to prevent the rise of monopolies or oligopolies in network products as seen in telephony, where monopolies emerged in countries like France, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the United States, despite such regulations. Moreover, ex-ante regulation can slow innovation, as regulated prices offer incumbents assured returns, who then create entry barriers under the guise of regulatory compliance.

While there are no simple answers, lessons can be learned from the growth of the internet—despite being a monopoly, it has managed to ensure consumer welfare while fostering innovation and creativity. The government could create statutory mechanisms to govern network economy products, ensuring all stakeholders are on equal footing. The government may refrain from directly prescribing solutions but retain overriding powers in matters of national security, sovereignty, or significant public interest. Effectively addressing this disruptive economic phenomenon will require an out-of-the-box solution.

Quantum Computing

The classical digital world is on the brink of disruption with the emergence of quantum computing (QC), capable of solving problems in minutes that would take advanced supercomputers thousands of years. Countries like China, France, Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom are at the forefront, and India must catch up. The cabinet’s approval of the Indian National Quantum Mission (INQM) is a significant step forward but greater industry involvement is crucial.34 In India, QC research has primarily been conducted by government-owned labs, whereas global advancements have been driven by industry and startups. QC is capable of revolutionizing sectors such as pharma, healthcare, finance, logistics, aeronautics, and space. To harness this potential, India needs policies that incentivize industry leaders and startups to engage in R&D. Additionally, an industry-led framework for testing, certifications, and standards must be developed to keep pace with evolving knowledge.

Conclusion

India’s journey toward becoming a “tech-first” nation is both ambitious and inspiring. The government’s strategic initiatives, such as Digital India and the AI Mission, lay a solid foundation for continued innovation and digital transformation. However, staying ahead in this rapidly evolving landscape requires continuous adaptation, fostering homegrown talent, and strengthening cybersecurity measures for which the government has to lead from the front by crafting the appropriate policy framework. By leveraging its vast data resources, enhancing AI capabilities, and encouraging indigenous innovation, India can not only secure its position as a global technology leader but also ensure inclusive growth and digital empowerment for all its citizens—a model for countries across the globe.

*The author is a nonresident scholar at Carnegie India and the founder and chairman of Mounttech Growth Fund - Kavachh. The author would like to thank Charukeshi Bhatt, research assistant at Carnegie India, for her valuable assistance.

About the Author

Former Nonresident Senior Fellow, Technology and Society Program

Ajay Kumar is a former nonresident senior fellow at Carnegie India. He served as the defense secretary of India between August 2019 and October 2022 and is the longest serving secretary in Ministry of Defence, where he also served as secretary in the Department of Defence Production.

- Hidden Tides: IUU Fishing and Regional Security Dynamics for IndiaArticle

Ajay Kumar, Charukeshi Bhatt

- One Year of the INDUS-X: Defense Innovation Between India and the U.S.Article

Ajay Kumar, Tejas Bharadwaj

Recent Work

Governments around the world are in different stages of implementing artificial intelligence (AI) regulations. The European Union will start enforcing a comprehensive Artificial Intelligence Act this year;35 lawmakers in Canada and California have tabled AI safety bills, yet to become law; meanwhile, the United States, the United Kingdom, China, Singapore, and Japan are experimenting with different approaches, ranging from voluntary codes of conduct to targeted regulations for specific sectors and applications.36

In this essay, we question if it is the right time for India to adopt new AI regulations. So far, the Indian government has established a high-level committee to provide “strategic guidance” on AI regulation, while continuing to issue ad hoc rules and advisories to govern the development and use of AI.37 In the long term, a new Digital India Act is expected to cover AI regulation, though the current status of the bill remains unclear.38

Based on our ongoing research, we find that, at this stage, there is no clear justification for the introduction of new AI regulations in India. Rather, we need to better understand the novel risks posed by AI and identify the legal vacuum before adopting any new regulations. Further, there is a need to carefully study the dynamic AI ecosystem to identify specific market failures. For now, we recommend a tentative approach to regulation and highlight areas in which additional research is required to inform the policymaking process in India.

Understanding the Risks of AI

What are the new risks, if any, that can be uniquely tied to AI—a technology that has been around since the 1950s—that demand urgent regulation?39 Some say that generative AI applications like ChatGPT have exacerbated the risk of misinformation and bias on social media.40 However, since India already has systems in place to address these kinds of issues, both online and offline, would the costs of complying with new regulations be justified?41

To better understand the nature of AI risks, a panel of experts led by the “godfather of AI” Yoshua Bengio, identified three categories: (1) malicious use, (2) unintended consequences, and (3) structural risks (along with a fourth residual category). However, as the authors of the interim report themselves admit, it is impossible to anticipate every risk beforehand, evidenced by the fact that we are still grappling with the risks of large language models and generative AI applications.42 Therefore, the real question is this: does AI present novel or unique risks that we can reasonably anticipate for which new regulations are warranted?

When it comes to AI, risk classification may also be influenced by local factors, such as the levels of adoption, consumer awareness, and the rights and cultural sensitivities of a particular region. Similar to how the governments of the EU and Canada have identified certain high-risk categories of AI, we recommend that the Indian government conduct an evidence-based assessment of the risks of AI—grounded in local practices, legal rights, and value systems—before proposing any new regulations.43

Until a framework based on empirical evidence has been developed, we believe it is premature for India to adopt new AI regulations.

Identifying Gaps in Existing Laws

Another reason why introducing new AI regulations at this juncture may be premature is that we do not yet know if existing laws in India can adequately address the emerging risks of AI. Additionally, duplicating legal provisions could increase the volume of litigation and choke the already overburdened administrative and judicial system.

Therefore, we recommend a comprehensive analysis of existing constitutional protections, statutes, rules, regulations, and other provisions—such as those relating to digital content, privacy, and product liability—that may impact AI development and use. In some cases, a minor amendment may suffice to address anticipated risks.44 For example, to combat the growing threat of deepfakes, the government could update or reinterpret existing laws—in this case, the Information Technology Act, 2000 and the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (erstwhile Indian Penal Code, 1860)—to prohibit the generation and distribution of unlawful AI-generated content.45

In certain domains, however, disruption may be significant. For example, the explosion of AI-generated content based on copyright-protected material demands a thorough review of the Indian Copyright Act, 1957.46 A similar analysis of laws surrounding labor, data protection, and consumer protection would be useful to identify areas in which new rights, obligations, exceptions, or clarifications may be needed.

Observing Market Dynamics

An effective regulatory framework must also account for the role of different actors involved in perpetuating and mitigating the risks of AI. Market studies, like the one being prepared by the Competition Commission of India, will help regulators make informed choices by observing the roles and responsibilities of different actors in the AI value chain, their incentives and interactions, and their impact on other ecosystem participants.47 It would also help inform whether or not to adopt an ex ante approach to address specific market failures (an issue also being hotly debated in the context of the draft Digital Competition Bill).48

Market studies will also be important if and when the government plans to intervene on commercially sensitive matters, such as the sharing of revenues between creators and publishers in the context of AI-generated content—an issue that India’s IT Minister has indicated the new “AI law” will address.49 Because these issues are generally negotiated through contracts, the government will have to provide sufficient evidence of market failure if it intends to intervene on this topic through new regulations.

Similarly, market studies would also help determine who the regulations should apply to and the minimum thresholds for applicability. For example, key provisions of California’s AI safety bill only apply to advanced AI models that have been trained using a certain amount of capital;50 China’s generative AI rules only apply to entities that provide certain functions.51

Similarly, India’s AI regulations, if and when introduced, will have to be informed by the evolving market dynamics. Since the process of collecting such data is still underway, we believe it is premature to adopt new regulations at this stage.

Conclusion

Before adopting any new AI regulations, Indian policymakers need to have a thorough understanding of various factors: the unique risks posed by AI, the evolving dynamics of the AI ecosystem, the gaps in the existing legal framework, and the cost of implementing and complying with such regulations, among other considerations.

Without this foundational knowledge, adopting new AI regulations would be premature and could lead to unintended consequences that far outweigh the benefits. Based on our ongoing research on this subject, we find that there is a lack of sufficient information to provide a clear and compelling justification for new AI regulations in India at this stage.

In other words, now is not the right time to regulate.

About the Authors

Fellow, Technology and Society Program

Amlan Mohanty was a fellow with Carnegie India. His areas of expertise include privacy, content policy, platform regulation, competition and AI.

Former Senior Research Analyst and Senior Program Manager, Technology and Society Program

Shatakratu Sahu was a senior research analyst and senior program manager with the Technology and Society program at Carnegie India.

In August 2024, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) published a notice seeking to empanel agencies that can provide artificial intelligence (AI) services to academia, startups, the research community, public sector agencies and governments.52 The proposed empanelment process follows the allocation of Rs 4,564 crores (approximately $544 million) under the IndiaAI mission to build national AI infrastructure through public-private partnerships.53 This recent development demonstrates the strategic importance of compute to India’s AI vision and its goal of “nurturing homegrown AI expertise, attracting talent, and supporting startup ventures,” as stated in the MeitY notice.54

Other countries also see the value of strengthening their domestic AI infrastructure. For example, China aims to increase its compute capacity by thirty percent in the next two years; Japan is providing $470 million in government funding to build an AI supercomputer; and the United Kingdom intends to build sustainable compute capabilities to realize its AI ambitions. 55

Meanwhile, India’s unique approach to “democratizing computing access” raises important questions.56 What is the role of the government in this process? How will the resources be used? Who will get access? In this essay, we offer recommendations for the strategic and equitable distribution of compute across the country.

The Rationale for Priority Access

The acquisition of compute resources is typically a market-driven process in which buyers and sellers compete in the open market at prices determined through demand and supply. However, compute resources required to power the most advanced AI systems are globally scarce.57 Therefore, to help realize its strategic national AI objectives, the Indian government plans to acquire 10,000 or more graphics processing units (GPUs) and offer them as a service to certain “approved entities”—academics, startups, researchers, government agencies, and micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs).58

However, at this stage, it is unclear which entities will gain access to these resources and for what purposes. Below we outline three factors that could help inform this process.

- National security: AI is likely to have important applications in cybersecurity, data analytics, military simulations, and drone operations, though the extent to which it is currently being used to bolster India’s defense capabilities is not publicly known. For such sensitive applications, the government will need to establish dedicated compute facilities with additional access, control, and security measures. Further, the government may prioritize compute access for certain activities, such as securing borders, conducting surveillance, and analyzing intelligence reports. Based on this rationale, the primary beneficiaries of compute resources deployed by the government would be entities that engage with matters of national security, whether private or public sector entities.

- Strategic sectors: Another domain where there may be an urgent need for prioritized access to compute resources is in strategically important sectors. These sectors could be identified on the basis of their importance to India’s strategic bilateral partnerships, or “strategic sectors” in which the government intends to retain its presence through public sector units.59 Based on this rationale, access to compute resources may be prioritized in sectors such as AI, space, defense, telecom, semiconductors, and energy.60

- Scientific progress: With AI playing an important role in supporting fundamental scientific breakthroughs, the government should also consider enabling access to computing resources for scientific research that serves the public interest, such as in drug discovery, energy management, and astrophysics.61 However, the government should clarify if commercial applications in these domains will qualify for prioritized access.

Before allocating computing resources to any entity, the government should build a rationale around the fact that failure to provide such access would result in a loss of strategic or competitive advantage for India. The government may also consider other variables, such as the social and environmental impact of the proposed applications, to determine if they should qualify for prioritized access to computing resources. Once these strategic sectors have been identified, we recommend that the government carry out an assessment to understand their specific compute requirements, and then allocate the required resources to eligible entities. Further, to build public trust, the eligibility criteria and selection process must be fair and transparent.

Sustainable Models

The budgetary allocation of Rs 4,564 crores (approximately $545 million) to procure and deploy 10,000 GPUs under the IndiaAI mission is for an initial period of five years. With this in mind, we highlight two important considerations to promote its long-term viability.

- Given the rapid innovation in advanced chip technology, the government must ensure that the GPUs it acquires do not become outdated before they are provisioned for use.62 To mitigate this possibility, the government could stagger the acquisition of chips in tranches, and diversify its GPU stockpile with a combination of different models and technology service providers.63 Such experimentation could also help inform India’s choice of compute architecture in the long run.

- The government should analyze whether a capex or opex route would be most appropriate in the long run, given the specific objectives of the IndiaAI mission. In a capex model, the government will have to finance the procurement of GPUs upfront and set them up at its own expense, while also incurring maintenance and personnel costs.64 In an opex model, the government would rent or lease the GPUs from third-party service providers.65 However, while an opex model may reduce upfront costs, the infrastructure is usually under the physical control and supervision of a private third party. This could compromise the government’s desire for autonomy, especially in sectors pertaining to national security and sovereignty, such as defense, space, and telecom, where, for example, the government may want to activate a “kill switch” in case of an emergency.

Monitoring and Evaluation

As explained in a previous piece, there is a lack of reliable data on how existing compute capacity is currently being used, making it difficult to evaluate future demand and anticipate operational challenges.66 In fact, the lack of data on compute usage has prompted some to speculate that the introduction of GPUs into the Indian market may not be met with expected demand.

In light of this, we recommend an immediate audit of the National Supercomputing Mission (NSM) by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India or an independent committee of experts set up by the government, the details of which should be made publicly available.67 A detailed audit report would make clear who the current beneficiaries of the NSM’s compute resources are, what applications are being prioritized, and other operational details that would help inform the ongoing empanelment and deployment models in relation to the IndiaAI mission.

Going forward, continuous monitoring of India’s compute facilities will be critical to informing future policy, including whether the government should continue to procure compute resources on behalf of the public and private sectors or if it should be left to the free market.

Conclusion

While there is consensus that India’s government agencies, startups, and researchers need urgent access to compute resources, there are some open questions. It is unclear who the intended beneficiaries of the public compute facilities are and for what purposes these entities will be granted access to compute resources. The need of the hour is a clear rationale for prioritized access and transparency in the procurement and deployment process.

In the larger interests of this project, we recommend articulating clear eligibility criteria and diversifying the approach to procuring compute resources. Moreover, continuous monitoring and evaluation of such resource utilization will help inform long-term strategy and may even illuminate alternative pathways to democratizing access to compute.

About the Authors

Fellow, Technology and Society Program

Amlan Mohanty was a fellow with Carnegie India. His areas of expertise include privacy, content policy, platform regulation, competition and AI.

Former Senior Research Analyst and Senior Program Manager, Technology and Society Program

Shatakratu Sahu was a senior research analyst and senior program manager with the Technology and Society program at Carnegie India.

The inaugural meeting and substantive outcomes of the India-U.S. initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies (iCET), led by the national security advisers (NSAs) of the two countries on January 31, 2023, had been preceded by nearly two years of preparatory technical soundings, bureaucratic organizational assessment, and summit-level encouraging mandates.

Following their meeting on the margins of the Quad summit in Tokyo on May 24, 2022, U.S. President Joe Biden and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the launch of the iCET “to facilitate outcome-oriented cooperation. . . [and] forge closer linkages between government, academia and industry of the two countries in areas such as AI, quantum computing, 5G/6G, biotech, space and semiconductors.”68

There were several factors that led to the establishment of such an initiative:

- These emerging technologies were assessed as having the potential to transform work and living. Accordingly, it was prudent for the two countries to build a forward-facing partnership to sustain and consolidate their growing economic, technological, and strategic collaboration.

- Despite years of negotiation and effort, both sides had been unable to conclude even a limited trade agreement due to existing interests on either side blocking concessions that could enable mutual compromises. A new framework for technology collaboration would lead to co-development, sharing of new production, and opportunities to explore complementary trading facilitation.

- In many countries, these technologies were in the early stages of development. A new technology partnership could present the potential strategic advantage of staying ahead of the curve.

- The United States has an established ecosystem for cutting-edge innovation which could be of advantage to India. In turn, the United States would benefit from a partnership with a country of 1.4 billion people and significant skilled manpower—reflected, inter alia, in the impactful presence of Indian-origin persons in the tech ecosystem of Silicon Valley and the growing number of global capability centers coming up in India, as it dealt with the economic, technological, and military challenge from China.

The NSAs meeting was preceded by a joint meeting with representatives of industry and academia from both countries on January 30. The iCET fact sheet released after their bilateral meeting on January 31 spoke of the objective “to expand strategic technology partnership and defense industrial cooperation,” and “noted the value of establishing ‘innovation bridges’ in key sectors.”69

Significant decisions taken included establishing a standing mechanism, later called the Strategic Trade Dialogue, to resolve regulatory barriers. A new Implementation Arrangement for a Research Agency Partnership was signed “to build a robust innovation ecosystem” and a joint Quantum Coordination Mechanism was established between the two countries, along with increased collaboration on high performance computing.70 A new bilateral Defense Industrial Cooperation Roadmap was finalized, and on August 23, 2024, a Security of Supply Agreement was signed during Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh’s visit to the United States.71 A new “innovation bridge” to connect defense startups from the two countries (the India-U.S. Defense Acceleration Ecosystem, or the INDUS-X), has already convened thrice and announced joint challenges and awards.72 Bilateral collaboration on resilient semiconductor supply chains has grown—there have been at least six subsequent announcements by U.S. companies for new investments in India for assembly, testing and packaging, innovation, engineering, and skills development related to semiconductors.73 There have also been new efforts in space through cooperation in human spaceflight, and the involvement of the Indian private sector in select NASA programs.74

The launch of the iCET generated new momentum for the India-U.S. relationship. It was seen as a joint signal that high-level technology cooperation was also now warranted from the national security perspective, in contrast to the United States’ effort to build a “small yard, high fence” to restrict such collaboration with China. The United States authorized 80 percent technology transfer to India for GE 414 engines—higher than what it had authorized for any of its other partners.75 Two Indian tech startups have since received orders from the U.S. Space Force.76 One of them is now collaborating with U.S. defense company General Atomics in semiconductors for defense.77 Several subsequent joint statements, including the one after Modi’s state visit to the United States in June 2023, spoke of technology being a defining feature of the partnership.78 The Democratic Party platform for the November elections, released mid-August, referred to “investing in a twenty-first-century partnership” with India “that builds technology into the fabric of our cooperation.”79 Continuing disagreements on some international issues, particularly Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, were limited in their impact on the overall relationship because of cooperation frameworks such as the Quad and the iCET.

Along the Lines of the iCET

Several U.S. allies and partners have sought to arrive at a similar framework for cooperation with India.

The European Union and India set up a Trade and Technology Council (TTC) in April 2022. This was the EU’s second such mechanism after that with the United States, formed in June 2021, that aimed at coordinating policy with respect to the China challenge. With India, the TTC aimed to give impetus to ongoing trade and investment negotiations and enhance technology collaborations. Though the TTC had a ministerial-level meeting in May 2023, the mechanism has not yet led to any pathbreaking outcomes.80 Bureaucratic energy on both sides has remained focused on trade negotiations where progress has been slow due to differences in level of ambitions. A better approach may be to delink technology collaboration explorations from trade discussions, as was done in the iCET, and have different bureaucratic leads on both sides, with a focus on tech partnerships.

The India-U.S. Memorandum of Understanding on semiconductor supply chain and innovation partnership, for instance, was signed on March 10, 2023, under the framework of the commercial dialogue after the launch of the iCET. It sought to “establish a collaborative mechanism” on semiconductor supply chain resiliency and diversification, and to “leverage complementary strengths… through discussions on various aspects of the semiconductor value chain.”81 This was an example of technology collaboration and investment decisions leading to work on supportive trading and supply chain facilitation agreements.

The UK and India launched a Technology Security Initiative (TSI) on July 24, 2024, along the lines of the iCET, that recognized “the increasing role of technology in national security and economic development.”82 Like the iCET, the India-UK TSI would be “coordinated by the National Security Advisors of the two countries. . . . (who) will set the priority areas and identify interdependencies for cooperation on critical and emerging tech that will, in turn, help build meaningful technology value chain partnerships.” The TSI explicitly recognized what was implicit in the iCET process: new opportunities that would enable trade and supply chain partnerships flowing from technology collaborations and resultant production-sharing in areas related to high-technology sectors. Like the iCET, the TSI identified artificial intelligence, quantum, telecommunications, semiconductors, biotechnology and health technology, advanced materials, and critical minerals as areas of initial focus. It also set up a process led by India’s Ministry of External Affairs and the UK government “for promotion of trade in critical and emerging technologies, including resolution of licensing or regulatory issues.”

The United States had also announced, in December 2023, an initiative with South Korea for a critical and emerging technology partnership, which mentioned the start of a triangular India-U.S.-RoK cooperation.83 Officials from the three countries had a follow-up meeting in March 2024.84

Thus, the iCET has significantly impacted the India-U.S. bilateral relationship and offered a template for partnerships with other countries. But there is considerable potential for more.

The Way Forward

It is now time to assess the potential challenges that could arise while taking the initiative forward in the coming years. The United States presidential elections in November 2024 will bring a new U.S. National Security Council (NSC) leadership that will need to continue to see a stake in partnerships such as the iCET that can mobilize different parts of the U.S. bureaucracy to adjust rules and procedures and overcome lingering questions about the long-term benefits of such partnerships with India.

There will be bureaucratic challenges in India too. The Indian NSC was not structured to deal with issues related to technology for development. However, it is the only body that can be an effective interlocutor for the U.S. NSC. Even as different ministries, departments, and institutions under the government of India pursue cooperation in areas kickstarted by the iCET, they must periodically assess overall progress, potential bottlenecks, and the need for higher-level institutional involvement to deal with such issues. Progress in an area of greater interest to the United States could be leveraged to ensure progress in other areas of greater interest to India.

The two countries must also recognize the advantage of being open to including new areas of collaboration under the iCET framework. A statement issued after a meeting of the deputy NSAs of the two countries in December 2023 mentioned critical minerals, rare earth processing technology, digital connectivity, digital public infrastructure, and advanced materials as areas to be considered in subsequent stages of the iCET.85 However, there is often a tendency to load extraneous elements onto a framework seen as succeeding or delivering. The iCET should remain focused on emerging and critical high-level technologies. Cooperation in these areas will no doubt create a willingness and confidence for more collaboration in areas that may have been absent so far. But those opportunities should continue to be pursued elsewhere while using the push generated by the iCET. Otherwise, the iCET process could veer off its original intent into no doubt important areas, but away from issues of critical high-level technology.

The private sector and academia lead many of these technologies, especially in the United States, and must continue to be actively involved. While government clearance is necessary, entities must see academic or business value in pursuing such collaboration. Commercializing and exploiting these technologies will also benefit India but cannot be done by the government alone.

After the U.S. presidential election results on November 5, the country will enter a two-month transition period during which the winning candidate will announce transition teams to receive briefings and handover notes in different government departments. It is essential that the U.S. NSC and NSA suitably lay out the advantages of the iCET. As in the past, the government of India will also need to effectively communicate its interest to the outgoing and incoming teams.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Carnegie India

Arun K. Singh is a senior fellow at Carnegie India. He has extensive experience across the globe, including as India’s ambassador to the United States, Israel, and France.

- TRUST and TariffsCommentary

Arun K. Singh

- India-U.S. Relations Beyond the Modi-Biden DynamicCommentary

Arun K. Singh

Recent Work

Introduction

The Indian Semiconductor Mission (ISM), announced in December 2021, has gotten off to a respectable start.86 Armed with a Rs 76,000 crore (approximately $10 billion) financial incentive package, the semiconductor incentive scheme, housed under the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY), has seen engagement from across the semiconductor supply chain.87 For instance, in June 2023, Micron Technologies announced an assembly and testing facility in Gujarat—an investment that was facilitated by the ISM. Outsourced assembly and testing (OSAT) facilities are also being set up by the Tata Group and Renesas and its joint venture partners in Assam and Gujarat, respectively.88 Another consequential announcement came in February 2024 when the Tata Group announced a partnership with PSMC, the world’s fourth-largest chipmaker from Taiwan, to set up India’s first commercial fab in Gujarat.89

Indigenous chip design has also been gaining momentum alongside these developments. About twelve Indian firms have reportedly been selected by the Centre for Development of Advanced Computing (C-DAC), the nodal agency under the Design-Linked Incentive (DLI) scheme, established to offer Indian firms financial support and chip design infrastructure.90 Though India remains a hub for chip design talent, the industry is largely employed by multinational semiconductor firms. Accordingly, India should seek to leverage this talent pool to become an indigenous chip design powerhouse through the DLI.

What should be the way forward for the ISM? What are some policy proposals that could be considered as India advances its semiconductor ambitions? In this essay, I offer two key recommendations to help build on India’s initial success.

- A Dedicated Scheme for Components and Sub-Components in Semiconductor Facilities: During the establishment of major assembly and testing facilities, such as Micron’s in Gujarat, other supplier firms also expanded their operations to these regions. These firms, though integral parts of the supply chain for Micron and other major tier-1 companies, were technically ineligible for incentives under the December 2021 policy as they were not directly involved in setting up fabs or assembly, testing, marking, and packaging (ATMP) units. However, these firms often specialize in very niche segments, such as providing printed circuit boards and packaging substrates, the latter being a device upon which semiconductor device elements are fabricated.91 Though ineligible under the primary scheme under the ISM, these firms could avail of incentives under SPECS, or the Scheme for the Promotion of Manufacturing of Electronic Components and Semiconductors.92 First announced in April 2020 by the MeitY, SPECS aims to provide a 25 percent financial incentive on capital expenditure on a certain list of electronics goods that comprise the downstream value chain for electronic products. SPECS has not been renewed after March 2024, though stakeholders have hinted at a SPECS 2.0 with certain tweaks. The previous SPECS guideline offered incentives on capital expenditure for a range of twenty or so products.93 However, the guidelines clubbed various products together, particularly under the label “passive components” without taking into account how the constituent components each had their own market dynamic and distinct financial requirements when it came to scaling production. A separate classification of components ought to be considered, each with its own minimum investment threshold.

- A Tariff Rethink: Indian contract manufacturing firms are reportedly struggling to meet the full demand from original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) for assembly operations under the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme for mobile handsets.94 Accordingly, much of the demand is being met through imports, most of which have tariffs on them. These high import costs increase the final cost levied by Indian enterprises since it increases their input costs.

For instance, a report by the Indian Cellular Electronics Association (ICEA) showed that while 47.2 percent of electronic imports pass through under zero tariff, the remaining 52.8 percent are subjected to varying levels of tariff, mostly above 10 percent.95 Indeed, camera modules—a key component of mobile handset manufacturing—have a 10 percent tariff levied on them under the Phased Manufacturing Programme (PMP).96

In the short run, it is worth considering whether tariff rates could be reduced to provide India’s domestic enterprises with cheaper inputs. With increased sales would come the financial wherewithal to increase scale, wherein a portion of the revenues from enhanced scale could be plowed back into research and development (R&D) to create original intellectual property. The PMP was meant to “promote indigenous manufacturing of mobile handsets.”97 However, it appears that PMP seeks to increase domestic value addition, particularly in those key components that are largely imported as of now, which the “domestic industry aspires” to manufacture.98 Intuitively, it should be asked, why are imports high in these components? Does the domestic industry not manufacture them efficiently due to a cost/know-how disadvantage? If so, then why promote parts of the domestic industry that are not competitive? Furthermore, since various components subject to tariffs under the PMP are part of a global supply chain, these components usually cross multiple borders, and even a small increase in customs duty payable can lead to an escalating cost disadvantage for Indian firms that import them.

As a caveat, however, it should be noted that India has recently made gains in onshoring supply chains. According to a recent policy research paper by the World Bank, India has been one of the primary beneficiaries of U.S. trade policy changes resulting from the trade war with China.99 Therefore, there are green shoots when it comes to India’s efforts to gain from China+1 initiatives of various companies. However, one should consider the counterfactual of whether more gains could have been made if tariff lines on certain products were lower. Even a parliamentary committee report has felt that more could be done.100

The 2023–2024 Economic Survey by the Government of India has also acknowledged a need to re-think their involvement in Chinese supply chains—“Developing countries will have to figure out a way of meeting the import competition from China and, at the same time, boosting domestic manufacturing capabilities, sometimes with the collaboration of Chinese investment and technology… India has a similar decision to make…It may have other risks, but as with many other matters, we don’t live in a first-best world. We have to choose between second and third-best choices… To boost Indian manufacturing and plug India into the global supply chain, it is inevitable that India plugs itself into China’s supply chain. Whether we do so by relying solely on imports or partially through Chinese investments is a choice that India has to make.”

Accordingly, tariff reduction in the short run should be considered, owing to the above reasons.101

Conclusion

India’s semiconductor initiatives were meant to attract major industry players to set up operations within the country, a goal that has been partially realized. As India progresses to the next phase of the semiconductor mission, we ought to consider strategies to bring in players beyond anchor companies. The semiconductor market thrives when a full-fledged ecosystem of players works together in clusters. Addressing the challenge of fostering such an ecosystem will be crucial for the ISM as it sets its sights on the next phase of growing India’s semiconductor ecosystem.

About the Author

Fellow, Technology and Society Program

Konark Bhandari is a fellow with Carnegie India.

- India Signs the Pax Silica—A Counter to Pax Sinica?Commentary

Konark Bhandari

- Revisiting the Usage of Refurbished Equipment in India’s Semiconductor EcosystemArticle

Shruti Mittal, Konark Bhandari

Recent Work

In the past decade, India’s bioeconomy has expanded thirteen times, growing from $10 billion in 2014 to $130 billion in 2024, with projections to reach $300 billion by 2030.102 The private sector has been the main driver of this growth, bolstered by government initiatives such as dedicated research laboratories, centers of academic excellence in biosciences, national biotechnology parks, bio-incubators, and the establishment of the Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council (BIRAC) to support industry growth.103 The sector’s expansion has largely been driven by contract manufacturing in the biopharmaceutical sector, which includes the production of vaccines, diagnostics, biotherapeutics, and biosimilars for international companies.104

India’s competitive manufacturing costs attract global biopharma companies looking to reduce production expenses. Its cost-effective vaccine production has positioned it as the leading supplier of the DPT (Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis) and measles vaccines.105 During the coronavirus pandemic, India’s biotechnology industry experienced significant growth, driven by its capability to develop, manufacture, and supply low-cost vaccines worldwide.106 As a major supplier of generic drugs, India is also expanding its presence in developed biosimilars markets, like in the United States.107

Indian companies have historically maintained a strong track record of exporting pharmaceutical products to regulated markets across the globe, where they have demonstrated efficacy and popularity. However, recent concerns about the quality of drugs produced in India have raised serious concerns, especially following incidents like the deaths of children in Gambia linked to toxins found in India-made cough syrups.108 In another case, a cancer drug manufactured by Indian manufacturer Intas was banned by the United States, citing negligence and weak regulatory oversight.109

While India’s ability to deliver cost-effective medicines globally is well-established, ensuring consistency in quality is essential for sustaining trust, reliability, and long-term efficacy.

India must address several additional challenges to advance further along the biopharma value chain and become a global biopharmaceutical innovation hub.110 Key among these is the need to create infrastructure to foster linkages between industry and academia and develop policy mechanisms conducive to sector growth.

Industry-Academic Collaboration for Research Commercialization

Public and private sector institutions often operate with differing incentives and objectives when it comes to basic research and development (R&D), leading them to work in isolation from each other.111 Government labs typically focus on long-term fundamental research aimed at publishing high-quality academic papers, while the private sector prioritizes research with commercial potential. Academic researchers also often lack industry connections, which can delay the translation of promising research into market-ready products.112

A notable example is the Rotavac vaccine. Although the strain was first discovered between 1985 and 1986 in the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Delhi, the first commercial vaccine was only made available in 2016 by Bharat Biotech.113

This case illustrates how disjointed public-private collaboration in India’s biopharma sector can slow the commercialization of vital healthcare products, which could otherwise be deployed more rapidly to save lives. Enhancing knowledge transfer between academia and the private sector is crucial to leverage the unique strengths of both entities and expedite the market delivery of biopharmaceutical products.114 Such collaborations could, in the long run, facilitate the swift development of vaccines and other biopharma products against emerging pathogens with pandemic potential.

Regulatory Fragmentation and Bureaucratic Hurdles

The introduction of the Rotavac vaccine in the market was delayed because multiple approvals were required from agencies under different ministries. Although the Biological Research Regulatory Approval Portal (BioRRAP) under the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) has simplified the application process for conducting biological research in India, this system still lacks a streamlined process for obtaining product commercialization approvals, which remains a significant bottleneck.115

Products generated by the biotechnology industry in India are still regulated by departments under four different ministries: the Ministry of Science and Technology; the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change; the Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers; and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.116 Lack of coordination among these concerned ministries, coupled with challenges in tracking applications, often leaves firms stuck in bureaucratic delays and poorly defined regulatory processes.

To address these challenges, corrective measures have been adopted by the Indian government. In a recent move, clinical trials were waived for drugs for Alzheimer’s, weight loss, and cancer approved by regulators from Japan, Australia, Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, or the European Union.117 This step greatly expedites the introduction of drugs in the Indian market and reduces the cost of clinical trials for drug manufacturers in India with manufacturing licenses from international companies, thereby helping maintain drug affordability. Additionally, during the coronavirus pandemic, regulatory approvals were streamlined to accelerate the commercialization of vaccines and diagnostics in India. Electronic submission of regulatory documents was also introduced to expedite submissions and reviews. It is, therefore, crucial to institutionalize these pathways for critical and innovative biotechnology products beyond emergencies.

A system must be put in place for online submissions to track applications and exchange information between different regulatory departments. This approach will ensure that instead of duplicating the review process, one ministry can build on the approval of another, thereby reducing the time required for regulatory approvals. Implementing a regulatory sandbox could provide companies with alternatives to test their innovative products under regulatory supervision. Furthermore, investing in the training of regulatory personnel is important to enhance their ability to handle and review complex biotechnology products.

Conclusion

For India to advance in biopharmaceutical innovation, it must enhance academia-industry engagement to effectively translate research into marketable products. Maintaining drug quality is crucial to sustaining its global positioning as the “pharmacy of the world” and regulatory reforms are essential to expedite the approval of biopharma products. To achieve its 2030 goals, India should capitalize on its strengths in the biopharmaceutical sector to pave the way for a resource-efficient and innovative bioeconomy.

About the Author

Former Associate Director, Fellow, and Chief Coordinator, Global Technology Summit, Technology and Society Program

Shruti Sharma was an associate director and a fellow with the Technology and Society Program at Carnegie India, where she is currently working on exploring the challenges and opportunities in leveraging biotechnology to improve public health capacity in India. Additionally, she is the Chief Coordinator of Carnegie India's Global Technology Summit.

- The India-United Kingdom Technology and Security Initiative: Ideas for ChangeArticle

- +1

Rudra Chaudhuri, Tejas Bharadwaj, Konark Bhandari, …

- The India-U.S. TRUST Initiative: A Resilient Pharma Supply ChainCommentary

Shruti Sharma

Recent Work

Introduction

In June 2020, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), under the Department of Space (DoS), introduced reforms to open India’s space sector to private players.118 Several steps have been taken since to support these reforms—the establishment of the Indian National Space Authorization and Promotion Centre (IN-SPACe);119 the release of the Indian Space Policy, 2023120 with implementation guidelines;121 and the liberalization of the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) policy for the space sector.122 These reforms spurred Indian private participation in the $630 billion global space market and led to the creation of 189 space startups, as of 2023, in the country.123 They also facilitated ISRO’s gradual shift towards strategic programs, while space companies aimed to cater directly to the commercial market.

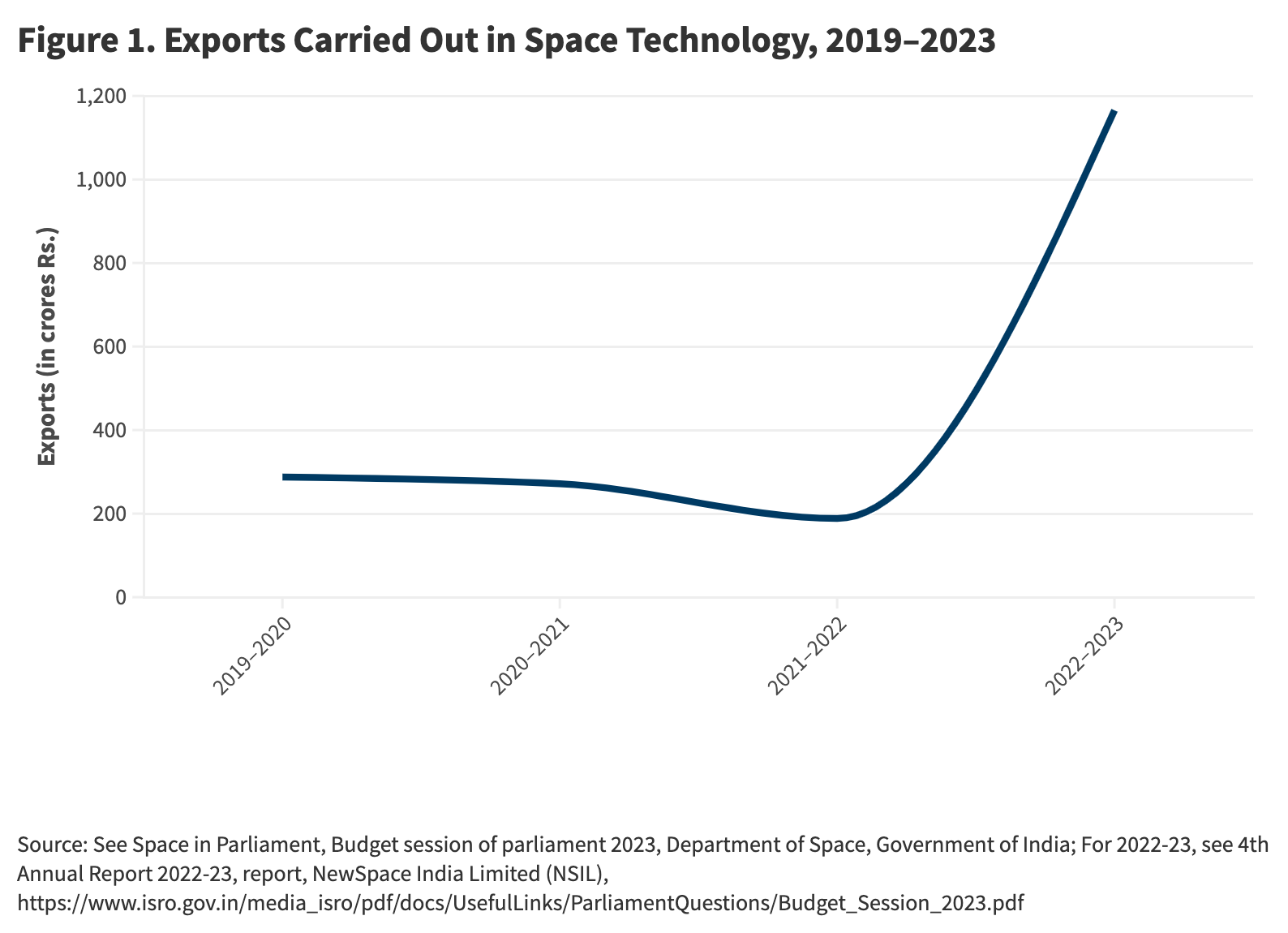

In 2023, IN-SPACe released a decadal vision and strategy for India’s space sector, highlighting its objective to grow India’s space economy from the current $8 billion to $44 billion by 2033.124 Notably, the vision aims to increase India’s space exports to $11 billion, about Rs 92,100 crores, by 2033—one-fourth of its envisaged market goal. This underscores the importance of space export expansion for India to actualize its vision and further space exports as a foreign policy instrument.

In, 2022–23 India’s space exports were valued at over Rs 1,165.52 crores, about $138 million, comprising launch services, mission support services, products, and space segment communications.125 India’s space exports must grow at a rate of 54.8 percent per annum to reach $11 billion by 2032–33. In this essay, I evaluate the viability of India’s long-term goals for its space sector and answer the following questions: Is India on course to achieve its space exports target? And what does it need to do in the next five to ten years to do so?

| Financial Year | Exports (in crores Rs.) |

| 2019–20 | 287.53 |

| 2020–21 | 271.46 |

| 2021–22 | 188.40 |

| 2022–23 | 1165.52 < |

Is India on Course to Achieve $11 Billion in Space Exports by 2033?

Experts have noted that the export forecasts in the decadal vision are ambitious and currently look difficult to achieve.126 They have, however, noted that such an ambitious goal could motivate the Indian space sector to near the $11 billion mark.127

One of the primary concerns towards nearing this goal is that India’s space exports declined [see figure above] over the last few years, barring the spike in 2022-23 triggered by ISRO’s launch of eight foreign commercial payloads.128 As of September 2024, ISRO has not launched a single foreign commercial payload.129 Further, satellite and launch vehicle exports, excluding services in 2023–24, were $1.79 million, a 93 percent drop from 2022-23. According to the 2023–24 launch manifest, just one foreign payload launch has been scheduled by ISRO —the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Proba-VI—in late 2024.130 Further, India’s estimates of total space exports for 2023–24 remain to be seen.