Just over a week ago, Hilal al-Assad was killed when Islamist rebels pushed into the coastal province of Latakia. As head of a local wing of the National Defense Forces (NDF), Syria’s main pro-government militia, he was given an official funeral in Latakia on March 24 before being transported to his final resting place in Qardaha, the Assad family’s ancestral village.

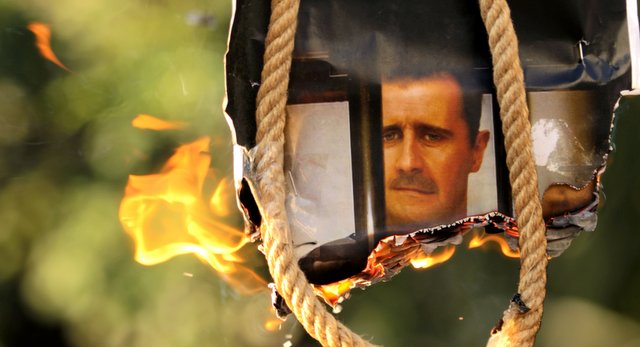

Hilal al-Assad’s father Anwar was a half-brother of the late president Hafez al-Assad—this was a death in the family, one of very few for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. There was of course the June 2012 death of General Assef Shawkat, the deputy minister of defense, former head of the Military Intelligence Directorate, and husband of Bashar’s sister Bushra. But since then, the core elite of family members seems to have survived relatively unscathed by the war. That matters greatly to regime stability in a state where family name is far more important than official titles or constitutional prerogatives—at least if that name is Assad.

Not a Career Soldier

Hilal al-Assad’s own career is instructive in that regard. Virtually all other NDF commanders (there’s one per province) are career officers, typically at the rank of colonel or brigadier general. But despite commanding one of the most important NDF branches, that in Latakia, Hilal al-Assad was not a military figure at all.

Prior to his funeral, Hilal had mainly turned up in the media as president of the Syrian Arab Horse Association. And the state news agency, SANA, which will ritually rattle off the titles and decorations held by fallen commanders when reporting their deaths, could not come up with anything better for Hilal al-Assad than saying he had “a master’s degree in economics and planning.”

Before the uprising, Hilal ran the state-owned Military Housing Establishment’s office in Latakia. The company was created in the 1970s to organize housing and infrastructure for Syria’s rapidly growing army, but it soon outgrew its primary purpose and began to gobble up ever-larger chunks of the real estate market—much to the benefit of its directors, their relatives, and army allies, all of whom grew fat on bribes and kickbacks. At its peak in the mid-1980s, the Military Housing Establishment was a politico-military empire in its own right, and the author Patrick Seale dryly noted that “all it needed was a flag and an anthem.”

Still, a career in construction and corruption will not necessarily make you a skilled military commander. The real reason for Hilal al-Assad’s installment as NDF chief on the coast was of course his loyalty, his money, and his access to the halls of power in Damascus and Qardaha, rather than any sort of military expertise. It was, essentially, because he was an Assad.

From Office Manager to Militia Organizer

When the uprising began in March 2011, the Syrian government soon found it necessary to bolster the repressive apparatus by drafting civilian supporters, propping up Bashar al-Assad’s rule with a chaotic movement of pro-government vigilantes and militia factions. In Latakia, members of the ruling family were among the first to take up the task, drawing on their state connections and previous involvement with the criminal underworld.

Among them was Hilal al-Assad, who began to buy up unemployed youth to help suppress demonstrations, allegedly paying salaries of up to $200 a month to gangs of what the opposition termed “shabiha.” These groups later evolved into the NDF, with Hilal al-Assad slipping out of his suave executive suits and into a more suitable set of army fatigues. Some things stayed the same, though: according to reports from local activists, the Assads’ choice of location for a new detainment camp in Latakia fell on a former horse stable.

An Out-of-Control Son

Making Hilal al-Assad commander of the NDF in Latakia had consequences, however—such as unleashing his own immediate family on the province. Suleiman al-Assad, Hilal’s twenty-something son, has become infamous for his thuggish behavior during the uprising. Exploiting the fact that he is untouchable to local authorities because of his family, he stands accused of a variety of scandals and of harassing inhabitants of Latakia City.

The Lebanese paper al-Akhbar—which has an otherwise pro-Assad editorial line—refers to Suleiman as “an unending nightmare” for the city’s inhabitants and claims he was even briefly arrested in October 2013, allegedly on orders from the presidential palace in Damascus. But the arrest didn’t last long: soon after, Suleiman al-Assad was back in trouble, reportedly having pulled a gun on a cousin—who hails from another powerful, regime-connected Alawite clan—inside the Naval Academy of Sciences. The quarrel resulted in the cousin being shot in the foot and in yet another exasperated al-Akhbar article.

Rule by Blood Has Its Downsides

The personalization of power in Syria, where Bashar al-Assad rules through family more than he does through institutions, has been a source of strength for him. The blood ties that stretch out across Syria from Qardaha were easy to mobilize when the uprising began in 2011, and they have kept the president in power ever since, acting as a solid core of the regime and enforcing loyalty on less enthusiastic backers while helping to stave off the risks of an Egyptian-style internal coup.

But the Assad family isn’t much loved, even by regime supporters. Its long history of arrogance and corruption, and the regime’s consistent prioritizing of family interest over state interest, is what originally set off the Syrian uprising. And what the Assads have gained from family cohesion, they lack in institutional endurance. As one of many cousins of the president, Hilal al-Assad was perhaps on the outskirts of absolute power, but his death will still have come as a chilling reminder to the elite in Damascus of how precarious their position really is—because even if the Syrian regime is able to weather an insurgency of tens of thousands, a handful of well-aimed assassinations could still puncture it from within.