- +6

Yasmine Farouk, Nathan J. Brown, Maysaa Shuja Al-Deen, …

{

"authors": [

"Michele Dunne"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Diwan",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Middle East",

"North Africa",

"Egypt",

"Iraq",

"Syria"

],

"topics": []

}

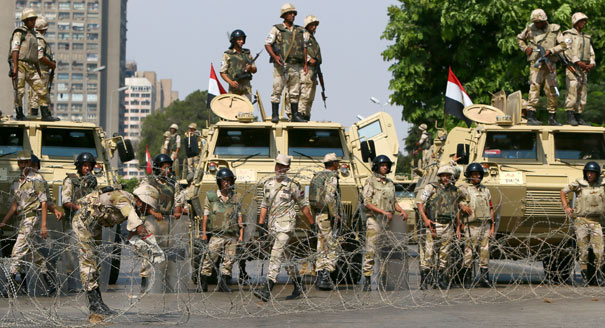

Source: Getty

What Egypt Can and Cannot Do Against the Islamic State

In the struggle against the Islamic State, Egypt needs sound political and economic policies that will quench the spread of violence and extremism within the country itself.

U.S. President Barack Obama’s recently declared strategy against the so-called Islamic State, a Sunni extremist organization that now controls vast swathes of Iraq and Syria, calls for the building of an international coalition. Alongside Jordan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and other Gulf states, Egypt is often mentioned as a critical U.S. ally in the Arab world.

As Egypt is a longtime security partner of the United States, and one that sent troops to the 1991 Gulf War to liberate Kuwait, many assume that Cairo will have a significant military role to play in the fight against the Islamic State as well. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry recently bolstered the impression of Egypt’s “critical role” by including Cairo in his tour of the region, by touting Egyptian Sunni Muslim institutions as key to the ideological fight against extremism, and by stressing the importance of defeating extremists in the Sinai.

Limited Military Capabilities

Some of this makes sense and some of it does not. Egypt has a large and well-equipped army, but it is unlikely to play any significant military role in Iraq or Syria. The ground offensives against the Islamic State will be carried out by local forces, essentially the Iraqi army and Kurdish peshmerga forces in Iraq, and Syrian rebels in Syria. There is—at least for now—no need for large numbers of soldiers from Arab countries such as Egypt. In addition, Egypt lacks the air force and special forces capabilities, local intelligence, and tribal connections that some other Arab states possess, including Jordan, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar.

However, Egypt can most likely be relied on to continue allowing U.S. military overflights and refueling, as well as expedited Suez Canal transits for warships (for which the U.S. government pays a handsome premium). Those are routine features of the bilateral relationship that have continued even after the U.S. administration suspended some military assistance following Egypt’s July 2013 military coup that ousted then president Mohamed Morsi.

Complicit Islamic Institutions

It is also unlikely that Egypt will play the “critical” ideological role Kerry apparently had in mind when he described the country as “an intellectual and cultural capital of the Muslim world.” Egyptians and other Sunni Muslims susceptible to recruitment by the Islamic State are unlikely to pay heed to statements by the grand sheikh of al-Azhar, Ahmed el-Tayeb, or the grand mufti, Shawqi Allam; many consider them to be no more than civil servants who put out a government-sanctioned brand of Islam. This is especially so after the 2013 coup that removed Morsi from power and led to a ban against the Islamist political movement to which he belonged, the Muslim Brotherhood.

Al-Azhar University itself has since been the site of pitched battles between students sympathetic to the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood and a university administration affiliated to the Egyptian government, leading to restrictive new rules. Such practices, as well as new controls by the Ministry of Religious Endowments on who may preach at mosques and what may be said, will continue to drain these institutions of their credibility in the eyes of exactly those who may be vulnerable to Islamic State propaganda.

Moreover, even when the grand sheikh or grand mufti speak on the topic—and they have already done so after the Egyptian government determined that it was in its interest to discredit the Islamic State—they may do so in ways that the United States finds unhelpful.

Tayeb tackled the “tarnished and alarming” image of Islam created by the Islamic State in televised remarks on September 8. But he did so by promoting a conspiracy theory according to which the Islamic State is a “creation of colonial powers in the service of global Zionism.” As evidence, Tayeb offered the contrast between Washington’s hesitation in confronting the Islamic State in 2014 and its readiness to invade Iraq in 2003. Even if the sheikh now changes his message to suit the shifting views of the Egyptian government, it is hardly likely to bolster his credibility as a messenger.

A Questionable “War on Terror”

Egypt does, however, have an important role to play in combating the spread of the Islamic State. It is one that Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shukry identified during a September 11 conference in the Saudi city of Jeddah: to “fight its own battle” against terrorism. Egypt faces a dangerous homegrown insurgency, which has escalated sharply in the past year. Connections between the Islamic State and Ansar Beit al-Maqdis, a militant group based in the Sinai, remain murky but are a troubling possibility, and the Islamic State clearly appeals to many within the radical Islamist underground in Egypt.

And yet, even a cursory examination of Egypt’s “war on terror” reveals two major problems: the definition of the problem and the methods used to address it.

The Egyptian state continues to define the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist group, despite a lack of evidence for its involvement in violence. Government officials waste no opportunity to imply connections between the Brotherhood and the Islamic State, in a transparent attempt to gather international support for the massive post-2013 crackdown against the Brotherhood, as well as against all other Islamist and secular critics.

The political repression and human rights abuses associated with this crackdown, which are on a scale not seen in Egypt’s modern history, are a recipe for breeding recruits to Islamist militancy and ideologies such as that of the Islamic State. Even when it comes to groups that clearly fit a U.S. definition of terrorism, such as Ansar Beit al-Maqdis, the repressive tactics used by the Egyptian state are worrisome. The collective punishment of Bedouin residents in the Sinai, already bitter after decades of economic and political neglect by Cairo, is likely to only further alienate this segment of the population.

Fight Extremism by Fixing Egypt

So, when Kerry says that Egypt plays a critical role in combating regional terrorism, he is completely correct—and mostly incorrect when it comes to how Egypt should do so.

What is needed in the struggle against the Islamic State is not Egyptian troops in Syria or Iraq, or more sermonizing by Egypt’s discredited state-controlled clergy, but sound political and economic policies that will quench the spread of violence and extremism in Egypt itself—a country that may otherwise grow ripe for exploitation by the Islamic State and like-minded groups.

Releasing the thousands of Egyptians that have been detained merely for nonviolent protests since the coup of 2013, ceasing torture and mistreatment in prisons, beginning a transitional justice process to deal with past abuses, restoring pluralistic politics and civic freedoms, extending economic development to marginalized areas such as the Sinai and Western Desert—these are the most important things Egypt can do to fight the spread of extremism in the region.

About the Author

Former Nonresident Scholar, Middle East Program

Michele Dunne was a nonresident scholar in Carnegie’s Middle East Program, where her research focuses on political and economic change in Arab countries, particularly Egypt, as well as U.S. policy in the Middle East.

- Islamic Institutions in Arab States: Mapping the Dynamics of Control, Co-option, and ContentionResearch

- From Hardware to Holism: Rebalancing America’s Security Engagement With Arab StatesResearch

- +8

Robert Springborg, Emile Hokayem, Becca Wasser, …

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Diwan

- Axis of Resistance or Suicide?Commentary

As Iran defends its interests in the region and its regime’s survival, it may push Hezbollah into the abyss.

Michael Young

- When Football Is More Than FootballCommentary

The recent African Cup of Nations tournament in Morocco touched on issues that largely transcended the sport.

Issam Kayssi, Yasmine Zarhloule

- Kurdish Nationalism Rears its Head in SyriaCommentary

A recent offensive by Damascus and the Kurds’ abandonment by Arab allies have left a sense of betrayal.

Wladimir van Wilgenburg

- All Eyes on Southern SyriaCommentary

The government’s gains in the northwest will have an echo nationally, but will they alter Israeli calculations?

Armenak Tokmajyan

- The Hezbollah Disarmament Debate Hits IraqCommentary

Beirut and Baghdad are both watching how the other seeks to give the state a monopoly of weapons.

Hasan Hamra