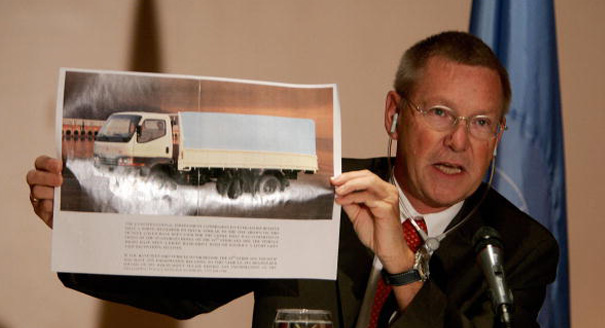

Eleven years ago, the German judge Detlev Mehlis was chosen by the United Nations to be the first commissioner of a team investigating the February 14, 2005, assassination of Lebanon’s former prime minister Rafik Hariri. At the time Mehlis was a senior prosecutor in the Superior Prosecutor’s Office in Berlin. After spending several months in Lebanon, he returned to his post at the end of 2005. In 2009, he served as head of the European Union Philippines Justice Support Program (EPJUST), an EU program in the Philippines to combat extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances. Today, Mehlis has retired and spends time between Germany and Majorca.

Michael Young: In 2005 you were appointed commissioner of the United Nations International Independent Investigation Commission (UNIIIC) looking into the assassination of Rafik Hariri, Lebanon’s former prime minister. This was seen at the time as a major step in ending impunity for political crimes. Was that ambition successful?

Detlev Mehlis: The murder of Rafik Hariri and 22 others was reason enough to establish an international investigative group to assist and support what was at the time the limited Lebanese capacities to identify the perpetrators. In my view, and judging from my eight months experience with UNIIIC, it was definitely worth the effort. In difficult times for the Lebanese people, the U.N. Security Council—including Russia—showed that it was willing to help Lebanon. The investigation revealed beyond a reasonable doubt the political elements behind the crime and their motives. It led to the ongoing trial in The Hague by the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, and will hopefully end with a just verdict.

MY: Wasn’t the danger of the investigation and tribunal that, unless they identified and condemned the guilty, it was always likely, thorough their failures, that they would highlight the shortcomings of international justice, therefore reinforce impunity?

DM: You have to realize that investigations, trials, and verdicts—international or national—never produce 100 percent justice. Sometimes they do, but most of the time they do not. That is part of trying to establish the truth: Sometimes you succeed, sometimes you do not. Most of the time it is both. You identify a few perpetrators, you send some of them to prison, while other criminals evade justice for whatever reason. That is the reality. Should the consequence be no investigations at all? I do not think so.

MY: You’ve been critical of the Hariri investigation for a long time. With the benefit of hindsight, how would you describe that experience? Were you right or wrong in your criticism?

DM: I admit that it is always easier to criticize than to perform, and of course my work has been criticized as well, which is normal for a prosecutor. Sometimes it is revealing to observe who is criticizing and why. With all that in mind I indeed became skeptical of a few things which happened after I and most of my team of international investigators had left the case. Whether I was right or wrong will be judged by others in the future, but I think I was right.

MY: Quite a few of those suspected of involvement in the Hariri assassination have been killed in recent years. Do you believe these were coincidences?

DM: I have no idea and as a former prosecutor I refrain from speculation. However, it is certainly most unfortunate that someone like Rustom Ghazaleh [the head of Syria’s military intelligence network in Lebanon at the time of the assassination] is no longer available for the Special Tribunal for Lebanon. Bashar al-Assad still is …

MY: Do you still follow the trial today? If so what are your thoughts?

DM: I do not follow it and the few times I tried, I found it most difficult to obtain information on what was going on. Therefore, I have no idea about the present status of the trial. It seems to have gone on for a long time, but there must be reasons for that. A major problem of international justice is that investigations and ensuing trials take too much time. I would favor a universally accepted code of criminal procedures for international cases, which should enable the trials to proceed more rapidly, without endangering the rights of the accused. In my view, justice delayed is justice denied.

MY: There was a hope in the 1990s that norms for international behavior were advancing. Yet the war in Syria showed the failure of such an aspiration. What do you see as the status of the effort to impose international legal norms of behavior on political actors in the world?

DM: As with ordinary criminals, international justice has only a limited deterrence effect on politically-motivated perpetrators. This is what we are seeing in Syria right now. The perpetrators on every level do not believe that they could end up in court one day, and indeed very few will under present conditions. What we need is an International Criminal Court that has the authority to open a case whenever it sees the necessity to act, and which has its own independent police body with universal executive authority.

MY: Given your experience of the Arab world in the past, and Syria in particular, does the carnage in Syria today surprise you?

DM: It does. I always assumed that the Syrian regime would somehow fail to outlive itself, that it would implode because of its criminal activities and structures. One day it certainly will, but apparently under more dramatic circumstances than I ever expected. Nowadays, I am appalled that the world is watching the tragedy in Syria and that Russia, which was supportive of the Hariri investigation in my time, is taking an active part in the murder of hundreds of thousands Syrian citizens.

MY: As a prosecutor in Berlin, you played a major role in the LaBelle discotheque bombing investigation and the investigation of the bombing by the international terrorist Carlos of the French Maison de France cultural center in Berlin, as well as numerous other cases. How would you compare your experiences then with what Europe is facing today, with homegrown terrorism by groups affiliated with the so-called Islamic State?

DM: The ideologies and the causes may be different, but the methods are pretty much the same: bombings of random or selected “symbolic” targets as well as the murder of civilians. We all saw it in the 1980s, against trains and train stations, airports and passenger planes, restaurants, newspapers and journalists, and so on. The only thing different nowadays is that most of the perpetrators are willing to sacrifice themselves when committing their crimes. It makes prevention more difficult, yet does remove the element of blackmail that was used to achieve the release of arrested terrorist criminals.

MY: In the past you have traveled to Paris to testify in the trial of Carlos. What kind of relationship exists between a prosecutor and the person he investigates? Does a sort of perverse form of intimacy develop?

DM: To effectively investigate a crime you have to understand the motive behind it. If you face a suspect, you try to understand—not respect—his or her personal motives, as well. In a way you have to be honest with the suspect and establish a personal relationship to obtain information. Almost every criminal is eager to talk about, justify, and explain what he or she did if he or she feels that the conditions are right. It is human nature. As an investigator you try to create the right environment for that. This is no intimacy, but professionalism.

MY: After all, such a relationship existed between you and a Syrian diplomat who transferred the bomb used in the bombing of the French Consulate in Berlin in 1983—a diplomat who later asked for political asylum in Germany.

DM: Professionally, everyone who helps me in solving a crime can count on my professional and personal assistance, within the legal limits. The Syrian diplomat to whom you are referring incriminated himself, his superiors in the Syrian Embassy, in the Foreign Ministry, as well as the terrorists, who all participated in the bombing of the French Consulate. This was valuable information not just for us in Germany but also for the Swiss, Greek, and French authorities. As I realized, this person would never be able to return to his family in Syria under the Assad regime. I did what I could to help him with his stay in Berlin after he was released from prison and after a few years we even managed to bring his family from Damascus to Berlin. Of course, his confession led to a more lenient sentence as well. But this can be done in our judicial system.

MY: How effectively is Germany dealing with the Islamic State challenge today? We’ve seen some attacks, but nothing on the level of what we’ve seen in France. Any reason why?

DM: We have been pretty lucky until now, but at the same time cooperation between our prosecutors, intelligence services, and police authorities is highly developed, structured, and therefore efficient. Years ago we established a formal consultation mechanism in which specialized officials at the working level, who know and trust each other, meet regularly at a well-equipped situation center, exchange information, develop strategies, and openly discuss individual cases and developments. We also use sophisticated technical means of investigation under judicial control.

I also see that many of our immigrants from the Islamic world to some extent identify with Germany, or at least appreciate the advantages provided to them by the country in which they live. This includes safe and comfortable living conditions, free education, free health care, the right to exercise their religion, freedom of speech, and so on. Therefore, people are willing to cooperate with or support the German authorities to prevent terrorist incidents. We experienced this recently when Syrian refugees assisted in the arrest of an alleged Syrian terrorist.

MY: Are the days of the crusading prosecutor over in Europe?

DM: They never existed. You have to understand that we are not on a television show. Effective prosecution—then and now—requires close cooperation with your international colleagues, the police and, where applicable, intelligence agencies. Without teamwork you are lost. Of course you have to be determined and focus on what your job requires: responsibility, obedience of the law, and respect for the victims

MY: With a career like yours retirement must be a bit dull. Is your retirement dull?

DM: No, not at all. Life is wonderful without corpses, sleepless nights, long workdays, and time-consuming meetings, just to name a few advantages. There was a time for prosecuting—some 40 years—now is the time for living.