Following a recent trip to Morocco, in the aftermath of the October 7, 2016, elections, I was able to better observe the rollercoaster ride of the government’s formation. What it showed me is that Morocco’s politics are changing, but also that there is much continuity when it comes to the supremacy of monarchical power. That is why many Moroccans have doubts about whether the new government will be able to achieve very much, even though the country has made definite progress in several other regards.

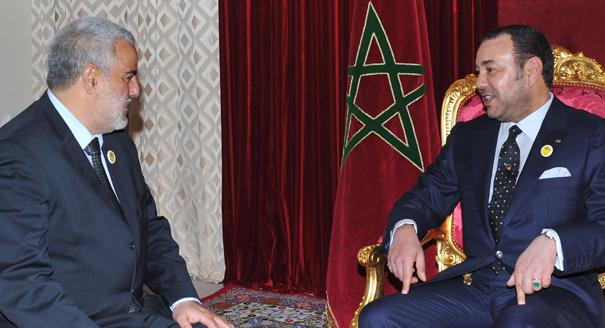

In the elections, Morocco’s mainstream Islamist party, the Justice and Development Party (PJD), won 126 out of 395 seats. Its leader, Abdelilah Benkirane, was asked by King Mohammed VI to form a government. However, within a few months the process had ground to a halt. While Moroccan academic Maati Monjib noted that this was an unprecedented victory for any party in Morocco’s history, given the multitude of parties in the country and the way elections are set up, the PJD had to form a coalition government. This task was complicated by the fact that the PJD’s main rival, the Party for Authenticity and Modernity, would not join a government headed by the PJD. This forced Benkirane to negotiate with smaller parties, prolonging the process.

The government’s formation was unprecedented in its length and complexity. However, what made things different was that Benkirane had the audacity to end negotiations when he did not get his way. Believing he was in a position of strength, based on the PJD’s electoral performance, the prime minister-designate did not feel he had to settle for a coalition that would weaken his party and prevent it from implementing its agenda. Armed with this belief, he held steadfast to secure the PJD’s advantage. However, as the delay in forming a government stretched on for six months, Moroccans became increasingly divided over whether Benkirane’s approach was in the best interest of the country, or even in the best of interest of the PJD. Though Benkirane’s unwillingness to compromise was a matter of disagreement within the party, it presented a united front.

In my conversations with party members and supporters, there were those who viewed Benkirane’s negotiations as principled and in line with his desire to create a strong government capable of completing the reform programs that he had started during the previous five years as prime minister. His stance was admired particularly among the more politically engaged youth—not just within the PJD, but also those who sympathized with them and had grown tired with the way politics are often dictated from the palace. The consensus among many is that Benkirane—and the PJD—have not been coopted by the king. Many among Morocco’s liberal middle class have chided Benkirane for emphasizing traditional values, but even they begrudgingly have acknowledged that he has attempted many ambitious programs, such as reducing the budget deficit, even if the PJD’s record fell well short of its promises.

This mixed assessment may miss the most important thing about Benkirane. He is increasingly viewed as a leader, someone close to the people, a rare politician who appears willing to fight the Moroccan political establishment for what he believes.

Among PJD youth, Benkirane is not just seen as a political figure but as a national leader with vision, charisma, and wisdom, reminiscent of the assassinated opposition politician Mehdi Ben Barka, someone rare to be found among Moroccan politicians. One young PJD member recently related a revealing story. His elderly grandmother who knows little Arabic was unaware of his involvement with the PJD, and generally ignores politics. But she often described Benkirane in glowing terms and looked forward to hearing him speak. Another young member explained that while campaigning in a remote village, he was asked several times if he was “with Benkirane,” in which case he was welcomed.

Despite Benkirane’s many detractors, this type of popular appeal, in which he is admired and seems to have his own legitimacy independently of his relations with the palace, makes the monarchy nervous. This has led to a view among some that the palace, by not putting pressure on the political parties to agree to the PJD’s coalition terms, sought to undermine Benkirane by showing him to be incapable of forming a government. Very likely such thoughts were behind the king’s decision on March 15 to ask Benkirane to step aside and allow another PJD official, Saadeddine Othmani, to form a government.

A SOLUTION OR A REVERSAL?

The king’s appointment of Othmani, a staid PJD leader and former foreign minister, was aimed at breaking the prevailing deadlock. However, the PJD rank and file was surprised and angered by the subsequent shift in the party’s position, particularly as it had seemed united behind Benkirane. As events would show, this unity proved tenuous.

At various points after the elections, it looked as if Benkirane was set to form a government with some of his former coalition partners, and possibly the nationalist Istiqlal Party. However, troubles emerged with one former coalition partner, the National Rally of Independents (RNI), which demanded the inclusion of other parties in the coalition. The RNI’s new secretary-general, Aziz Akhannouch, a wealthy businessman and former minister of agriculture and fisheries, wielded significant influence over the process, though his party had won only 37 seats. The RNI formed a bloc with the Popular Movement (MP), the Constitutional Union, and the Socialist Union of Popular Forces (USFP). Benkirane rejected the inclusion of the USFP in the government. To some PJD members, this reflected his dislike of the USFP and its leader Driss Lachgar, while others felt Benkirane was resisting the dilution of his party’s control over the government.

Othmani took a very different tack. In a little over a week he announced that he had the coalition required to form a government, which he did two weeks later. His coalition would include six parties, among them the RNI, the Party of Progress and Socialism (PPS), the MP, together with the Constitutional Union and the USFP. This sudden reversal of course on the USFP—especially after months when Benkirane had refused such an outcome, presumably with party support—left the PJD in disarray. Disagreement within the party grew between those who felt betrayed by Othman’s decision and a faction of the leadership that had supported him in forming a government with so many dissenting parties. This feeling of betrayal was particularly palpable among PJD youths, who took to Facebook to voice their dissent, with some claiming they were resigning amid fears of a split within the party.

While the sting of the party’s reversal lessened in the following weeks, there was still uncertainty over how to handle this setback. In my conversations with PJD figures close to Benkirane, they indicated there were possible ways to mitigate the impact. Perhaps by isolating Othmani’s government from the rest of the party, while not breaking with it, they could put some distance between the two and indicate that not all party members were on board. They even spoke of playing a sort of opposition role to the government so that it would not undo Benkirane’s perceived gains in maintaining the party’s independence from the palace. Such approaches, while not readily feasible, were notable for a party that prides itself on discipline and unity.

In addition to the big question of how to handle this disagreement, other big questions remained regarding Benkirane’s political future. What would his role be within the party and how might he influence the government? These questions, or some of them, will presumably be answered at the next party congress, which may come in the fall. Until then, the PJD will continue to grapple with leading a weak government that, as some have pointed out, is “unrepresentative of the people’s will” and will likely be beset by internal struggles making it unable to push through reforms. Othmani did stress that many of the reforms undertaken during the previous PJD-led government would continue, however few doubted the difficulties he would face in this regard.

THE MONARCHY IS FIRMLY IN CONTROL

While true power remains in the hands of the monarchy, the higher expectations of many Moroccans for a government not completely dependent on the palace left them disappointed with the outcome. This was particularly true of those who still hoped that the post-2011 constitutional changes in the country would spur political dynamism and increase citizen engagement. Across the political spectrum there was a feeling that the PJD had been compelled to accept a weak government, and that this represented a setback for Morocco’s political development.

This reality only highlighted the palace’s mixed signals with regard to political openings in Morocco. Over the course of his nearly eighteen years of rule, Mohammed VI has sought to portray himself as a reformer and a different sort of ruler than his father Hassan II, who was wary of political change. Yet restrictions on dissent and criticism persist, as does serious curtailment of the freedoms of press and expression. The constitutional revisions of 2011 gave political parties more latitude to play a role in governance, but they did not change fundamental power dynamics in Morocco’s political system. Not only does the king remain the ultimate authority, the palace continues to intervene in popularly elected governments. The previous government under Benkirane did attempt to play a larger governing role, not independently from the monarchy but as a way for Benkirane to take some ownership of his government’s work. However, Moroccan governments do not generally do that; they work at the behest of the king. Benkirane’s government acted as though it worked at the behest of the people.

That is perhaps what was behind the palace’s drive to prevent Benkirane from forming a new government, or ensuring that the PJD’s margin of maneuver would remain limited if it managed to do so. Such a constraint is almost guaranteed in a government composed of six political parties that lack a clear sense of what unites them.

For Moroccans who want to believe that their country is on course for greater democratization, the potential for problems in the government compounds popular frustration. They resent the heavy hand of the monarchy over political life, or its enabling of clientelism, crony capitalism, and pervasive corruption. Yet this attitude also overshadows what has been accomplished. Indeed, in recent years Morocco has seen considerable economic dynamism and a drive to bring in foreign investment and jobs.

For example, Morocco has developed its automobile manufacturing and assembly capabilities, with major automotive producers such as Renault-Nissan active there and expanding. PSA Peugeot Citroen is also planning to build a major plant in the coming years. In addition, Boeing signed an agreement with Morocco in fall 2016 to bring company suppliers into the country as part of an “ecosystem” that would help create jobs in the coming years.

Major infrastructure projects that could produce long-term economic dividends are also being put in place, such as the much-touted high-speed rail link between Casablanca and Tangier, which is expected to begin running in 2018. In this context, to some Moroccans a number of major development projects appear to be prestige items, aimed at boosting the kingdom’s international profile at the expense of spending where it is most needed. Indeed, many parts of Morocco remain chronically underdeveloped. The protests that started last fall in Al-Hoceima, following the death of a fish vendor, highlighted how many regions in the country remain underserved and disenfranchised.

AFRICA CALLING

A sign of dynamism is that Morocco has been increasing its stake in Africa. The decision to engage more with the continent economically is part of a broader diplomatic effort to regain leverage in the protracted Western Sahara issue. But it also makes good economic and political sense. Mohammed VI and senior members of Morocco’s foreign-policy establishment have made multiple trips to African countries as part of this endeavor.

Morocco is looking to invest in the banking, real estate, telecommunications, agriculture, and mining sectors. Among its ambitions is the building of a natural gas pipeline along the coast from West Africa to Morocco. In concert with these economic initiatives, and facilitated by them, Morocco has secured accession to the African Union. This step is seen not only as potentially beneficial for Morocco’s policy on the Western Sahara, but also to project the country’s economic, diplomatic, religious, and cultural influence. Morocco’s effort to reassert itself in Africa has become a point of national pride in the face of perceived Algerian attempts to hamper Morocco’s role in Africa, where Algiers has historically had greater influence due to its support for anticolonial movements.

Beyond economics and diplomacy, Moroccans take particular satisfaction in the religious role the monarchy and their country can play across Islamic Africa. Morocco has been looking to harness growing religiosity as a response to the increasing appeal of both Wahhabism and Muslim extremism internationally—something it has also sought to do with mixed success at home. Countering extremism in Africa is driven by recognition that insecurity in West Africa and the Sahel could affect Morocco; but also by a sense that as a country with a longstanding Islamic identity and a king who claims the title of Commander of the Faithful, Morocco offers a compelling vision of Islam.

Moroccans are united around the monarchy, which has kept the peace and for which popular support has remained consistent. But the king has also stood against reform and progress at times, and people will continue to speak out against this. Still, Morocco seems to be at a hopeful moment. There are greater opportunities for development and progress than there have been in years. Those aspiring to independent politics and a system devoid of corruption may be dismayed, but can take heart in the growing confidence of Moroccans to voice their demands and speak for what they believe is right.

The legacy of a more politically engaged population that has shown an interest in the PJD’s experience, and has been encouraged by Benkirane and his approach, will not be undermined by the way he was shunted aside. Morocco’s economy is growing; its outreach to Africa affords it new economic opportunities. And in contrast to rulers in much of the rest of the Arab world, the king remains legitimate and political stability does not appear to be under threat. Within this context, protests, strikes, and other forms of popular activism could keep avenues open for both reform and stability.