The Trump administration’s decision earlier this week to withdraw nearly $100 million in assistance to Egypt and suspend almost $200 million more is significant for two reasons. First, most of those funds are for military assistance, which has not been cancelled before, whereas economic assistance has been on a number of occasions. Second, the measure was linked directly to human rights concerns, an unusual step for any administration and certainly for the present one.

What exactly did the State Department—which is empowered to release foreign assistance once Congress provides the funds—do? It reprogrammed (translation: took away from Egypt) $95.7 million in assistance, including $65.7 million in military and $30 million in economic assistance. These funds were sitting around unspent from recent years (and there is much more of that, particularly economic aid) and the Trump administration decided to cancel them to send a signal.

The other step the State Department took was to preserve—but up on a shelf, just out of Egypt’s reach—an additional $195 million of military assistance that would have reverted irrevocably to the U.S. Treasury by September 30 if no action had been taken. This sum represents 15 percent—which Congress had subjected to human rights conditions—of the $1.3 billion in military assistance budgeted for Egypt in fiscal year 2016. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson in one sense did what his predecessor John Kerry had done: he said Egypt had not met the conditions, but waived them for “national security” interests. But then Tillerson put the funds on a shelf, saying Egypt would not be allowed to use them until (according to the State Department spokesman) “we see progress on democracy.”

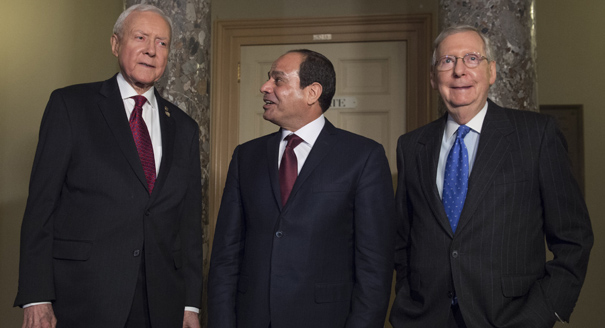

Why did the State Department take these steps, and why now? Looming Congressional action probably drove the decisions. Senior members of the U.S. Senate, many of them Republicans, have grown increasingly worried about Egypt and irritated with President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, as was apparent during a hearing (convened by Senate appropriators, who decide on foreign assistance) in which I testified in April. The festering wound of the 2013 conviction of American non-governmental organization (NGO) workers, a draconian new law that has shackled Egypt’s civil society, ongoing and extensive human rights abuses, and the reported use of U.S.-provided equipment in extrajudicial killings in the Sinai are among the issues that have soured some important senators on the relationship with Egypt. Had the administration failed to engage on these issues, Congress might have written tough new legislation on aid to Egypt. So the administration decided to seize the initiative.

The State Department has not made public what “progress” is required to release the $195 million, other than to say it has something to do with human rights and NGOs. That is probably deliberate and wise. Presumably, specific conditions have been conveyed privately to the Egyptian government, and one can speculate as to what they might be. Most likely there is something related to amending or overturning the NGO law. Tillerson has been clear and public about the fact that Sisi’s ratification of the law, after administration officials thought they had been promised the opposite, is a bone of contention. Overturning the conviction of American NGO workers and ceasing related harassment of Egyptian human rights groups might also be on the list.

Those issues figure prominently in congressional concerns, as does establishing proper end-use monitoring of American-provided equipment used in Sinai. Finally, Egypt’s long-running military and commercial relationship with North Korea has emerged as an irritant; the White House made public in early July that Trump had raised the issue in a call with Sisi.

Is the withdrawal of assistance out of synch with how the Trump administration has dealt with human rights globally and with Egypt specifically? Yes and no. It is unusual for any administration, and even more so for the Trump administration, to take a friendly authoritarian regime to task for abusing human rights and civil society. Trump’s loud statements, and Tillerson’s quieter ones, about not being concerned with how other nations govern themselves would seem to be at odds with this decision.

However, in other ways the step fits in with Trump’s approaches: doing things differently than former president Barack Obama (whose administration spoke about human rights abuses but was reluctant to withhold military assistance), demanding specific steps in exchange for U.S. assistance (think Pakistan), and showing that Trump drives a harder bargain than his predecessor.

Regarding Egypt specifically, since Trump took office observers have paid too much attention to his expressions of regard for Sisi and too little to his administration’s lack of enthusiasm (not to mention that of Congress) for translating photo ops into tangible support. When Sisi visited in April 2017, it was almost impossible to get journalists to note this fascinating dichotomy, so fixed were they on the “Trump-has-abandoned-human-rights” narrative.

While the Trump approach might well be confusing or incoherent, it also seems to be an effort to turn the Obama approach on its head: instead of public criticism with little real pressure, public friendliness accompanied by particular demands. It might be weeks or months before it is clear whether the Trump method works better than what we had before.