The government’s gains in the northwest will have an echo nationally, but will they alter Israeli calculations?

Armenak Tokmajyan

{

"authors": [

"Perry Cammack",

"Daniel Benaim"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Diwan",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Middle East",

"Iran",

"Iraq",

"Levant"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform"

]

}

Zero-sum efforts to “roll back” Iranian influence in Iraq are likely to backfire, but a better approach exists for Washington.

Reports that Qassem Soleimani, the leader of the Qods Force of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), paid multiple visits to Iraqi Kurdistan in the days before the October 16 Iraqi army advance into Kirkuk have triggered renewed bouts of anxiety in Washington. Amid fears of an American retreat and an outsize Iranian role in Iraq, the Trump administration has begun to speak the language of “rollback.”

Iran unquestionably holds significant sway in Iraq. That two Shi‘a-majority countries sharing an almost 1,500-kilometer border and the painful memory of a decade-long war should both view their relationship as strategically important is not surprising. Nor is Iran’s desire to capitalize on—and periodically contribute to—Iraq’s political dysfunction, weak institutions, and sectarian tensions. Until recently, this approach also greatly benefitted from the isolation of Iraq by most of the Sunni Arab states.

But the authors’ experiences in Iraq, including recent travel by one of us to Baghdad, suggest a more complex picture of Iranian-Iraqi relations.

The greatest counterweight to Iran’s influence remains Iraqi national identity. Outside of Kurdish areas, Iraq is experiencing something of a nationalist moment. This follows military victories by the government against the Islamic State in Mosul and its recapture of Kirkuk. For all the country’s profound challenges, non-Kurdish Iraqi political figures increasingly speak in terms of a national identity. After the most comprehensive defeat to date of Iraqi rejectionist politics, Sunni Arab factions, at least in Baghdad, are beginning to reflect what might be described as a “new Sunni realism” as they consider how to restore ravaged communities that see themselves as the Islamic State’s first victims.

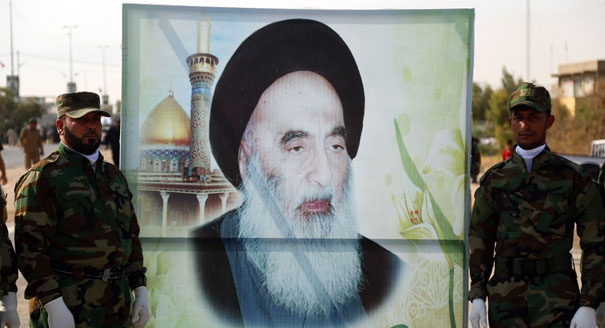

Even—or perhaps especially—the Shi‘a clerical establishment in Najaf takes a dim view of Iranian interference. Under the guidance of Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, Najaf has remained faithful to its quietist tradition, articulating a distinctly Iraqi concept of a “civil state” and holding Qom’s adoption of wilayat al-faquih, which effectively gives the supreme religious leader paramount political power, in no small disdain as historically anomalous. Iran would certainly like a more pliable replacement for Sistani. But when the Qom religious establishment recently sent a clerical emissary for just this purpose, he reportedly received a frosty reception.

Since coming to power in 2014 in the aftermath of the Islamic State’s capture of Mosul, Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi has struggled to maintain a delicate balance between Tehran and Washington, both key anti-Islamic State partners in Iraqis’ eyes. But the warming of Saudi-Iraqi relations, which began tentatively after former prime minister Nouri al-Maliki’s ouster in 2014 and has rapidly picked up pace in recent months, seems to enjoy widespread popular support.

Rather than simply lay claim to its Sunni coreligionists inside Iraq, Riyadh wisely began courting Shi‘a factions as well, signaling that it sought national partners rather than local proxies. Iraqi Shi‘a leaders, including from the pro-Tehran wing of the Da‘wa party, have privately expressed their support for their government’s outreach to Saudi Arabia. If the effort can be sustained and kept separate from the Saudi-Iranian zero-sum competition, it might encourage disaffected Iraqi Sunnis to return to the political fold, and serve as an important source of reconstruction investment and regional integration.

It is too soon to know if Iraq, which since the 2003 American invasion has suffered as the object of other nations’ attentions, is finally taking its place as a regional actor in its own right. But clearly Baghdad sees value in a more balanced set of regional relationships as a means of asserting its independence and defending its sovereignty.

Nonetheless, bringing to heel the country’s Popular Mobilization Forces remains a profound security and political challenge. Najaf’s independence from Iran makes these groups even more important as a vector for Iranian influence. But here too, Iraqis paint a somewhat different picture. Where Americans see “Iranian-backed militias,” many Iraqis—Sunni as well as Shi‘a—describe young Iraqis who fought and sometimes died to liberate their country from the Islamic State. They acknowledge both the long-term challenge and the dangerous degree of Iranian influence over some fighters. But rather than confront them head-on (a crisis Abadi cannot afford right now), his government seeks to coopt, tame, and gradually downsize the militias under the auspices of the Iraqi state.

This more cautious Iraqi approach, while far from optimal, may well prove the most sensible one. Ironically, this was the same approach the U.S. military advocated a decade ago in dealing with restive Sunni militia groups—the Sons of Iraq—until the Maliki government cut them loose, contributing to the rise of the Islamic State.

None of this is to downplay Iraq’s major problems. The Islamic State has lost its caliphate but not its ability to wreak havoc. Kurdish politics, after years of decay, has entered a state of acrimonious upheaval. The explosive situation between Irbil and Baghdad has shattered the dominant Shi‘a-Kurdish political axis and will require pragmatic leadership, restraint from both sides, and proactive American engagement. The reconstruction of Iraq’s devastated post-Islamic State northwestern Sunni towns and villages could take a decade or more. Beneath Iraq’s ethnic and sectarian disputes lies a more fundamental need to redefine relations between citizen and state and address the rapacious corruption that relegated a richly endowed state to the International Monetary Fund’s beggar’s table. And Iraq’s Ba‘thist history is a stark reminder of the misuses of nationalism.

Anti-Iranian “rollback” no doubt has a certain rhetorical appeal to the Trump administration. But as actual policy it is disconnected from Iraq’s political reality, and it boxes in pro-Western Iraqi leaders who do not wish to turn their country into a battlefield for Washington, Tehran, or anyone else. Zero-sum swagger invites an Iranian escalation and risks unraveling the fragile political progress of recent months. This is comfortable ground for Iran, which has shown a consistent knack for capitalizing on instability inside Iraq. But there is some reason to suspect that Tehran, viewed by many Iraqis as imperially arrogant, may prove less adept at engaging with a more self-confident Iraq.

Recent developments give Iraq a fighting chance to forge an independent path. This is a direction Washington should support.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The government’s gains in the northwest will have an echo nationally, but will they alter Israeli calculations?

Armenak Tokmajyan

Beirut and Baghdad are both watching how the other seeks to give the state a monopoly of weapons.

Hasan Hamra

The country’s leadership is increasingly uneasy about multiple challenges from the Levant to the South Caucasus.

Armenak Tokmajyan

Recent leaks made public by Al-Jazeera suggest that this is the case, but the story may be more complicated.

Mohamad Fawaz

The U.S. is trying to force Lebanon and Syria to normalize with Israel, but neither country sees an advantage in this.

Michael Young