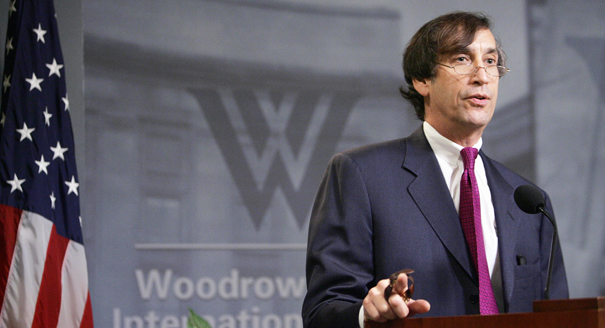

Aaron David Miller is currently vice-president for new initiatives and director of the Middle East program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. For two decades he served in the State Department as an analyst, negotiator, and adviser on Middle Eastern issues to Republican and Democratic secretaries of state. Between 2003 and 2006 he also served as president of Seeds of Peace, an internationally recognized program in conflict resolution and coexistence. He has written five books, including most recently The End of Greatness: Why America Can’t Have (and Doesn’t Want) Another Great President (Palgrave, 2014). His column “Reality Check” appears in Foreign Policy Magazine, and he is a CNN Global affairs analyst and a frequent commentator on NPR, BBC and Sirius XM radio. Diwan interviewed Miller in mid-April to get his perspective on Palestinian-Israeli negotiations and the rising tensions in the Middle East.

Michael Young: You were deeply involved in Arab-Israeli peace negotiations during the George H. W. Bush, Clinton, and George W. Bush administrations. Are these negotiations dead today, and do you feel that the efforts of President Donald Trump’s son in law, Jared Kushner, have any chance of succeeding?

Aaron David Miller: Since leaving government in 2003, my analysis of the peace process has been annoyingly and consistently negative. Partly, that was because I was no longer charged with coming up with ideas that I knew could never work. But largely it was based on what I saw with my own eyes and that I still see today. I am not with Groucho Marx on this one: Who are you going to believe, Groucho asks in Duck Soup, me or your lying eyes? Well, I know what I see.

You want serious negotiations that might have a chance of producing a two-state solution? Then you need three things that have never been present in the history of Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. First, leaders who are masters of their political houses, not prisoners of them and their respective ideologies, and have vision and pragmatism. Second, a sense of real urgency—pain and gain—which makes the benefits of changing the status quo more attractive than the risks of maintaining it. And finally, a third party, likely the United States, that has the will and skill to serve as a broker if both sides are willing to get serious. None of these factors is present today. So the chances of Mr. Kushner succeeding are slim to none.

MY: How did Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital affect the possibility of future negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians? Was it a final nail in the coffin, or just another obstacle on a difficult path?

ADM: The peace process was comatose well before the Trump administration decided to weigh in on the Jerusalem matter. But that decision made a nearly impossible mission harder still. In a single move, Mr. Trump created a trifecta of disasters: further shredding U.S. credibility as a broker; undermining the substance of the negotiating framework; and pushing the most sensitive issue relating to a final deal to the top of the list, at a moment when there’s no trust or confidence between the two sides and when they’re least prepared to deal with it. I can think of no single U.S. national interest that has been served by a decision driven primarily by domestic politics and Mr. Trump’s desire to be the non-Obama. Yes, the capital of Israel should be in West Jerusalem, but there was no compelling reason to do it now, and many reasons not to.

MY: For a long time U.S. officials have argued that, without a settlement, Israel will have to address the demographic factor, which is clearly to the Palestinians’ advantage. In trying to retain its Jewish nature, the country, it is said, will give up its democratic character. How do you see these dynamics playing out?

ADM: The demographic argument and its potentially catastrophic impact on the future of Israel as a Jewish, democratic state is a compelling one. Indeed Israel’s occupation is already taking its toll on the moral and ethical values that Israelis believed were to characterize the kind of state they wanted to create and sustain. Still, demography is a complicated and dynamic factor and will take time to play out, with many different twists and turns along the way. And by and large politicians deal with only what they are forced to at the moment.

Right now you have a one-state reality, with Israel in varying degrees controlling the West Bank and Gaza—a fact that bodes ill for the future and ensures at a minimum an on-again, off-again cycle of accommodation and confrontation. At the same time, given the dysfunction of the Palestinian national movement, Israelis may well believe the demographic issue is a manageable one. Gaza’s 1.8 million people are under Hamas’ control. The Palestinian Authority continues to govern roughly 2.8 million Palestinians, even though Israel maintains control over 60 percent of the West Bank. And the 300,000 Palestinians in East Jerusalem have a different relationship with Israel and the Palestinian Authority. The 1.8 million Palestinians who are citizens of Israel present a different set of challenges as a national minority. And Israel doesn’t appear to care much about Palestinians in the diaspora. Indeed, Israel will try to craft separate approaches toward each of these divided Palestinian constituencies in an effort to diffuse the demographic challenge and make it easier to manage. And a divided and dysfunctional Palestinian national movement is facilitating that process. Still, over time, an unresolved Palestinian problem and the challenge of controlling Palestinians directly or indirectly will guarantee continued conflict and threaten both the values and security of a democratic and Jewish polity.

MY: In the broader region, we see rising tensions between Iran and a number of Arab states, particularly in the Gulf, as well as Israel. To some observers, this will inevitably lead to armed conflict. Do you agree?

ADM: A rising Iran and a divided and dysfunctional Arab world seem to have set the stage for the kind of power imbalance that can trigger a more intensified struggle between Iran and the Sunni states. Add Israel’s concern with Iran’s role in Syria and you have an even more volatile mix. Make no mistake, Iran isn’t ten feet tall. But it faces an Arab world in which key Arab states seem to be either susceptible to Iran’s influence (Iraq and Syria), or, as in the case of Egypt, are increasingly preoccupied with their own problems. Indeed, if you asked me to name the most consequential states in and around the region today, I would offer up the three non-Arab states—Israel, Iran and Turkey. All are stable, all have tremendous economic potential, and all have more than credible militaries and intelligence organizations that allow them to project power into the region. Historically risk-averse Saudi Arabia, driven by the young and somewhat reckless Mohammed bin Salman, has paradoxically emerged to champion the effort to counter Iran, joined informally by Israel. Israel has already found itself in armed conflict with Iran, while the Saudis and Iranians are going at it in Yemen. But neither Yemen nor what happens in the Gulf seems to be the tripwire for major escalations. That candidate is Syria, where you have a deadly mix of rising Iranian influence and Israeli determination to push back, which might trigger a broader conflict, most likely between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon. It may well turn out to be a very hot summer in the region.

MY: We have seen very little U.S. diplomacy in the past year, to the extent that the United States seems absent on many fronts. What have the repercussions of this been in terms of U.S. influence in the Middle East?

ADM: Based on a good many years in negotiations, successful diplomacy requires at least two conditions: genuine opportunities where not just the United States is invested in trying to reach various agreements, and a U.S. administration that has the will and skill to take advantage of them. Looking at the region, one could easily argue that rarely has there been a moment when the prospects for successful diplomacy were more necessary and yet beyond reach. Whether it’s Yemen, the Saudi-Qatari cold war, the Syrian civil war, the Israeli-Palestinian issue, or the Iranian-Saudi standoff, the prevailing conditions have put bold and transformative diplomacy out of reach. The necessary conditions for success—urgency, local ownership, and finding the right balance of interests—are just not present.

To some extent third parties can help shape the environment in positive ways. However, they cannot manufacture the will or local politics to push parties into making really tough decisions, particularly when the gaps on substance and lack of trust are as wide and deep as the Grand Canyon. The United States is stuck in a region that it cannot transform or leave. So the middle ground is likely to be transaction and management, not resolution.

MY: On a personal level, do you feel that all your diplomatic efforts were for nothing?

ADM: Sadly, before I spent 20 years working on Arab-Israeli negotiations, I was a good deal taller. But seriously, despite all the mistakes we made, no I don’t feel it was a waste of time. The Madrid conference of 1991 got the parties talking. The 1990s was the only decade in the second half of the last century in which there was no major Arab-Israeli war. I suspect the interim agreements reached then, however flawed, saved some lives. And the July 2000 Camp David summit, even though it failed, likely produced some openings that might become part of an accord if one is concluded someday. But the lesson of my years working on negotiations is stark and compelling. Every breakthrough—between Egypt and Israel, between Israel and the Palestinians, between Israel and Jordan—was initially reached in secret, without the knowledge of the United States. The moral of the story is that you can’t make bricks without straw. Local ownership is critical. Without it, you might as well hang a “Closed for the Season” sign on any peace deals.