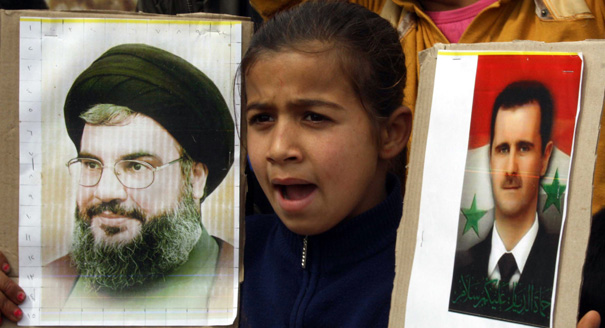

On March 8, 2005, Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah delivered a polarizing speech at a rally in Beirut. As the Syrian army was poised to withdraw from Lebanon after three decades of being deployed in the country, Nasrallah declared “Thank you Syria,” making reference to the Assad regime’s unwavering support for the Lebanese resistance against Israel. This moment was pivotal as Hezbollah took over many of the power nodes previously controlled by Syria, as well as management of its local networks. Syria’s men in Lebanon became Hezbollah’s.

Today, thirteen years later, a similar process is taking place in reverse, this time in Syria. Hezbollah, following six years of fighting there and thousands of dead and injured, looks set to decrease its presence in the country, under Russian pressure and with the Syrian regime’s acquiescence. As one Lebanese politician put it, now it is the Syrian regime’s turn to say “Thank you Hezbollah.” Or more accurately, thank you Hezbollah and Iran for all your efforts in defending the Assad regime, but no thanks for trying to turn Syria into another Iranian proxy.

Developments in Syria are also having repercussions in Lebanon. A reinvigorated Syrian regime is reclaiming some of its lost influence over Lebanese politics. This reemergence, while nascent, is occurring in parallel to mounting Russian pressure on Iran in Syria. Weeks after the Russian call for all foreign troops to leave Syria, a column in Al-Watan, a Syrian newspaper owned by President Bashar al-Assad’s cousin, criticized Ali Akbar Velayati, the Iranian supreme leader’s advisor on foreign affairs, for saying that Iran’s intervention had prevented a collapse of the Syrian regime.

Criticism is also being voiced on the other side. Last month, an Iranian parliamentarian warned that Syria and Russia were “sacrificing” Iran, and he even described Assad as “rude.”

Until last May, pro-Hezbollah media outlets in Lebanon had been pushing Acting Prime Minister Saad al-Hariri to sign a Russian-Lebanese military cooperation agreement, which would grant Russia’s military access to Lebanese bases. However, after tension last month between Russian military police and a Hezbollah unit on the Syrian side of the border with Lebanon, the party’s media went silent on the issue. Hezbollah had played a leading role in defeating the Syrian opposition in Qusair and its surrounding areas in 2013, which is why the party maintained a military presence there and leverage over local affairs. Lebanon’s northeastern border area is particularly sensitive for Hezbollah, as it is regarded as the place through which the party smuggles many of its weapons from Syria.

Since Lebanese parliamentary elections last May, spaces are opening up between the pro-Syria bloc in Lebanon and the pro-Hezbollah one. Acting Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil, the son in law of President Michel Aoun, is pushing Hariri to restore relations with Syria, arguing that this will facilitate the return of Syrian refugees, allow for a resumption of Lebanese exports through Syria’s Nassib border crossing with Jordan, and help give Lebanon a role in the Syrian reconstruction effort. Bassil, a presidential hopeful, most probably sees in Syria a political gateway to his own election.

The results of the parliamentary elections further empowered Syria. An array of politicians closely aligned with the Assad regime returned to the Lebanese parliament. Elie al-Firzli, a Greek Orthodox politician and longtime Syria ally who lost his seat after the Syrian withdrawal in 2005, encapsulated this resurgence. After his election as deputy speaker of parliament, Firzli stated, “I feel that a historic error has been corrected.” His return to a post that he had occupied during the years of Syrian hegemony symbolically affirmed a reversal of what had occurred in 2005.

Another parliamentarian, Jamil al-Sayyed, a leading security official during the Syrian era, has been taking a position similar to that of Bassil in pushing for closer ties with Syria. Sayyed was jailed for four years over his alleged role in the assassination of former prime minister Rafik al-Hariri. Recently, he criticized Saad al-Hariri for coordinating with Russia over a resolution to the Syrian refugee crisis, urging him instead to visit Damascus.

What is taking place today is not a split between Hezbollah and the Syrian regime, backed by Russia, which is unlikely. Rather, what appears to be underway is a renegotiation of the terms of their alliance. In the past, the Assad regime always retained flexibility on the international scene, often surprising Tehran and Hezbollah by negotiating with Israel—the last time in 2007 when the two sides engaged in what one Israeli minister described as “unofficial” talks. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s recent assurances that Israel would not oppose a resurgence of the Syrian regime if Iran withdrew its forces from the country surely reignited Iranian fears.

For now, Hezbollah seems intent on playing a larger role in the next Lebanese government. As U.S. sanctions against Iran kick in, the party might be left with few options other than to fall back on the home front, where many challenges beckon. Above all, the country faces a serious economic crisis that may have a harsh impact on Hezbollah’s economically vulnerable base of support.