Dalia Ghanem | Resident scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center

In his book titled Al-Joumhouriyya Ka’anna, or The So-Called Republic, ‘Alaa al-Aswany, as he does it all his novels, summons up several characters who are emblematic of Egyptian society and its mutations during the 2011 uprising. The book, translated into French as J’ai Couru Vers Le Nil (Actes Sud, 2018), has been banned in Egypt. The characters meet, fall in love, marry, fight, and even kill each other. All represent a unique facet of the Egyptian uprising, an event that changed their destinies and the destiny of their country. Aswany’s characters suffer from Egypt’s dictatorship, endemic corruption, social hypocrisy, and the use of religion to justify repulsive acts. For example, General ‘Aluani of State Security, though a devout Muslim who prays daily, tortures revolutionaries.

The events take place between January and February 2011, during which the hope for change among Egyptians reached its paroxysm. Aswany uses authentic testimonies to reveal the indiscriminate violence of the security forces against civilians, especially women who were subjected to virginity tests and sexual abuse. He also touches upon the generational divide between a young population that believes in change and an older one that refuses to fight, having lost all hope and become accustomed to dictatorship.

A powerful sentence is repeated by two of the characters—a young lady, Asma, who has been raped by members of the security forces and a disillusioned old communist activist, ‘Issam: “Egyptians like the stick of the dictator.” Aswany is not speaking here through the mouths of his characters. However, his accurate and poignant novel and the description of the youths’ disenchantment after the uprising does raise a crucial question: Did Egyptians believe in their revolt and were they ready for change?

Harith Hasan | Nonresident senior fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Center

More researchers are trying today to understand the resilience of authoritarianism in the Middle East, especially given the recent uprisings in many countries. This debate raises an important question: How do authoritarian regimes work? I recommend two recent books that address this question by studying the former Ba‘th regime in Iraq. They are primarily based on a careful examination of the Ba‘th Party archive, currently located at the Hoover Institution and the National Defense University, both in the United States.

The first book is by Lisa Blaydes, an associate professor of political science and senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University, and is titled State of Repression: Iraq Under Saddam Hussein. Blaydes analyzes the former regime’s behavior mainly by looking at its key decisions, the mechanisms for making them, and how the regime’s choices shaped subsequent events, including the war that led to its overthrow.

The second book is by Samuel Helfont, a lecturer in international relations at the University of Pennsylvania and a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia. It is titled Compulsion in Religion: Saddam Hussein, Islam, and the Roots of Insurgencies in Iraq. The book explains how the regime sought to control the religious sphere and instrumentalize religion, and it highlights the institutional framework and surveillance mechanisms employed to implement this policy.

The two books are worth reading for anyone interested in gaining a better sense of how authoritarian regimes operate, their organizational structure, decisionmaking processes, and responses to new challenges. At the same time, they provide a fresh look at the recent history of Iraq and the roots of several challenges that the country is still facing.

Lydia Assouad | Ph.D. candidate at the Paris School of Economics, research fellow at the World Inequality Lab, and El-Erian fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut

I have just finished reading Zoya Pirzad’s Mesl-e hameh asr-ha, in a French translation titled Comme Tous les Après-Midi (Like Every Afternoon). This is a series of short stories that portray the day-to-day life of Iranian women. By depicting their reality in a simple and refined style, Pirzad draws us into the lives of her characters from the very first lines. Yet, despite their realism, each story reads like a poem whose images lead to a deeper questioning of relationships, happiness, aging, and the position of women in society. Stockings, dresses, mugs, the Iranian dish fesendjan, curtains, all these everyday things are the beginning of a journey into the world of Pirzad’s female characters. The simplicity of these stories makes them pleasant to read while their poetry will allow you to travel to Iran without suffering from the heat.

Ahmed Nagi | Nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center

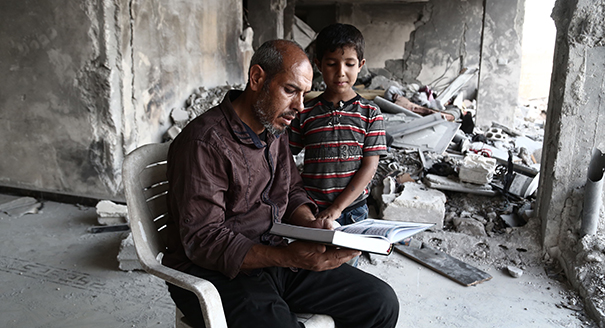

I would recommend a book published in Arabic, for those who can read the language, by Yemeni journalist Bushra al-Maqtari, whose title is translated as What Did You Leave Behind You? Voices from the Land of the Forgotten War. The book, published by Riad El-Rayyes Books in Beirut, appeared in 2018 and documents the impact of the Yemeni conflict on civilians. Maqtari seeks to understand better the human beings behind the casualty numbers that appear in media outlets. Her book is a collection of some 40 tragic testimonies, emphasizing the real cost of the devastating war that has been taking place since 2015.

In the first chapter, Maqtari describes her impressions when visiting areas that have been affected horribly by the conflict—San‘a, Ta‘iz, and Hodeidah. Her book, as she describes it, acts as a collective voice for the war’s victims and is a finger in the eye of the murderers and a blow against ignorance and forgetting. In the rest of her book, she gives space to the victims to tell us about their plight and pain, a pain that does not appear destined to end anytime soon.

Sherif Mohyeldeen | Nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center

With many eyes on Sudan right now, it would be beneficial for readers to pick up inspiring texts allowing them to see Sudanese social and political dynamics from up close. For anyone interested in knowing more about the country, the marvelous novels of Tayeb Salih and Hammour Ziada are a must.

Ziada’s The Longing of the Dervish, which won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature in 2014 and was shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2015, would be a very good place to start. Ziada succeeds in drawing a portrait that provokes different emotions and pain, by tracking the journey of a freed slave at the close of the 19th century, just as the Mahdist State was collapsing.

Ziada’s latest novel, The Drowning, was published last January and continues his special style of drawing a picture of daily life in Sudan, with a considerable focus on details and a remarkable use of language. However, the book has only been published in Arabic, so that readers who don’t know the language will have to wait a bit longer.

Michael Young | Editor of Diwan

Anshell Pfeffer’s Bibi is a highly readable biography of Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s most dominant politician of the past two decades. Pfeffer, a senior Ha’aretz correspondent, sees Netanyahu as the product of a dual legacy—that of the Zionist Revisionism of his father, Benzion, who was close to Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the “spiritual father of Israel’s right wing”; and of the United States, where Netanyahu grew up and embraced the Americanisms and media skills that would serve him well in communicating his political messages to American audiences.

Pfeffer argues that Netanyahu has ruled “thanks to the splintered Israeli consensus and his knack for inciting certain communities and sections of society against one another.” That tells us a great deal. First, that Netanyahu is both skilled and mediocre—an opportunist not a visionary. His gains on Israel’s behalf have represented political triumphs of sorts, but have also deepened the dilemmas of Israelis by blocking any lasting resolution of their conflict with the Palestinians. And second, that Netanyahu reflects well the spirit of this polarized age, which has allowed him to survive through multiple challenges and that may continue to serve him in the antagonistic years ahead.