Lara Friedman | President of the Foundation for Middle East Peace

Regardless of its ultimate composition, the next Israeli government, assuming one can be formed, will either be strongly or very strongly rightwing. On the Palestinian front, Israeli politicians’ annexationist aspirations and preference for security-military solutions over diplomacy align neatly with the ideological inclinations of Trump administration officials, President Donald Trump’s key supporters, and Republicans in Congress. As for Democrats, in the countdown to the 2020 U.S. elections fears of being attacked as anti-Israel or anti-Semitic are greater than ever. As a result, neither the White House nor Congress should be expected to play a moderating role with respect to whatever policies a new Israeli government is inclined to pursue, or is pressured by domestic forces to pursue, vis-à-vis East Jerusalem (including the Temple Mount-Haram al Sharif), the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip. Indeed, irrespective of continued noises about releasing the “Deal of the Century,” Washington is more likely to encourage, rather than challenge, the hardline policies of Israel’s next government.

Things are murkier when it comes to Iran. Developments such as the firing of John Bolton and Trump’s recent readiness to meet his Iranian counterpart likely left some Israelis worrying that the price of being handed a blank check on the Palestinian front could turn out to be U.S. policy on Iran that, if pursued by any other U.S. president, Israel would publicly have denounced as a betrayal. If there is no U.S. response in the wake of the recent attack on Saudi Arabia’s oil facilities—of the kind desired by Israel and Saudi Arabia—it will only strengthen concerns about Trump’s reliability on Iran. Either way, the next Israeli government will likely seek to make even greater common cause with Gulf Cooperation Council states toward keeping Trump firmly in the anti-Iran-diplomacy camp.

This dynamic could have interesting implications for the Palestinian track. Thus far, upholding the Israel-Gulf alliance has depended on Israel maintaining a pretense of commitment to resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But this has been undermined by Israel’s moves on Jerusalem, its actions in Gaza, and more recently public statements from politicians regarding plans to annex West Bank land. Going forward, the next Israeli government may be forced to balance inclinations toward pro-settlement-annexation policies in the West Bank and military adventurism in Gaza against what many Israelis view as an existential imperative to strengthen the anti-Iran alliance.

Ziad Majed | Associate professor at the American University of Paris, author, with Farouk Mardam-Bey and Subhi Hadidi, of Dans La Tête de Bachar Al-Assad (Solin/Actes Sud, 2018)

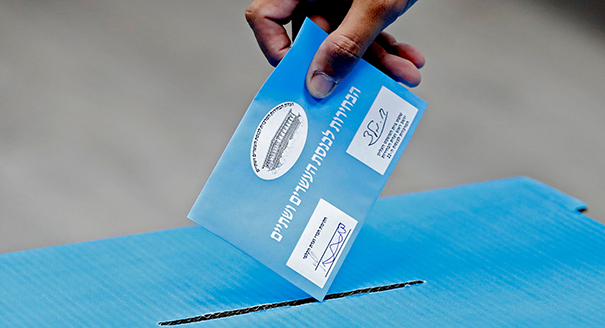

No clear majority has emerged from the Israeli elections. Neither Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu nor his main challenger Benny Gantz can secure a majority to form a government counting on direct allies. A national unity government is therefore a possibility. However, if Gantz sticks to his condition to exclude Netanyahu from any government he forms, only an internal Likud coup against the party’s leader would allow such a government to be established. Therefore, nothing is certain for now and a third election cannot be totally excluded.

At the same time, there is no reason to believe that any of the possible scenarios would bring radical changes to the Israeli-Palestinian situation or regional affairs. Even if Gantz evokes a return to the peace process, he remains very ambiguous on the settlement issue and Palestinian statehood. And in the event he were to form a national unity government, he would have to first convince his hardline rightwing partners of any change toward the Palestinians, even if these were minor. That is not guaranteed.

The same applies to the policy toward Iran and Hezbollah. Even if an escalation in tensions with Iran is slowed down by a Gantz-led government—a big if—this would not mean that the Iranian question will be any less of an Israeli priority. That is especially true given the strong backing of President Donald Trump, which Israel sees as an opportunity to deal with what they call “Iranian threats.”

Aaron David Miller | Former State Department advisor on Arab-Israeli negotiations (1988–2003), senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Israel’s so-called do over elections may well be remembered as among the most consequential in the country’s history for both good and ill. Here are some key trends that will mark the period ahead.

For the second time in six months, Benjamin Netanyahu has failed to gain enough votes to position Likud with other rightwing parties to cross the 61 seat threshold and form a government. The outcome is Netanyahu’s worst nightmare—no likely Knesset majority and a Likud unfavorably positioned to get a nod from the president to form a government. But Netanyahu, still prime minister, can’t be counted out yet. His party isn’t yet ready to abandon him; his formal indictment for corruption is still months away; and if there’s a national unity government with a rotation of prime ministers, Netanyahu will still lead Likud, a key partner in any prospective arrangement. Netanyahu can also hope that somehow the Trump administration’s peace plan or action against Iran will save him. But for the first time in years Netanyahu has been seriously weakened, and it is possible to imagine an Israel without him.

For 31 out of the last 42 years, Likud and the right have dominated Israeli politics. Three times Labor has won—twice putting forth former military chiefs of staff, Yitzhak Rabin and Ehud Barak, as successful candidates. Benny Gantz, also a former chief of staff, isn’t a politician. He ran a boring and lifeless campaign, and has no easy—or right now any—path to forming a center-right coalition. Relying on the Arab parties to support a government from the outside is possible, but a fraught affair. Indeed Ayman ‘Audeh, leader of the Arab Joint List, has said publicly he’s looking forward to being the first Arab to head the opposition. But in two elections now Gantz has held his own with Likud and could end up as prime minister in any national unity government rotational arrangement. Gantz represents the old Likud—tough on security, certainly no dove on peace issues, and committed to civility and the rule of law—qualities missing during the Netanyahu years.

Right now neither Likud nor Blue and White has easy paths to forming a government. And even though Israel has no written constitution, if no one succeeds in doing so the country will have its own “constitutional crisis” with a third election scheduled for early next year. Israeli President Reuven Rivlin has made clear that this must be avoided at all costs. And a national unity government is likely where Israel, for the seventh time in its short history, is headed. Gantz has said he won’t sit with Netanyahu as head of Likud. Lieberman, the coalition maker with nine seats, has said he won’t sit in any government with the religious parties. And Likud isn’t yet ready to abandon Netanyahu or its rightwing partners. Throw in the possibility of a Trump peace plan or a U.S. crisis with Iran and the volatility factor can only rise. If you thought the last six months was turbulent, buckle your seat belts. This is going to be one wild ride.

Zaha Hassan | Human rights lawyer and visiting fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Israeli Elections 2.0 have yielded no new earth shattering results. The next Israeli coalition government will either be rightwing or extremely hard rightwing. What does this mean for the ever-intractable Palestinian-Israeli conflict? If Likud and Kahol Lavon, or Blue and White, the two largest parties, form a coalition, I will be watching to see whether the more center-right Kahol Lavon with its three former Israeli military chiefs of staff at the top of the ticket will attempt to pull Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu back from his campaign promise to annex the Jordan Valley and Israeli settlements, given the security ramifications and likely international outcry. With U.S. presidential campaigning in full swing, a Likud-Kahol Lavon government might feel pressure to move ahead with annexation so that U.S. recognition of the action can be presented as a gift to President Donald Trump’s evangelical base ahead of the 2020 elections. If the only coalition that can be formed is a hard-right one that includes the ultranationalist and religious parties, then annexation is almost guaranteed.