Amir A. Afkhami, MD, Ph.D., is an associate professor with joint appointments in psychiatry, global health, and history at the George Washington University in Washington, D.C., where he the preclinical education director. He is also the author of A Modern Contagion: Imperialism and Public Health in Iran’s Age of Cholera (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019). His work focuses on the intersection of history, diplomacy, and domestic and global health policy. Afkhami planned and led the implementation of the U.S. State Department-funded Iraq Mental Health Initiative to rebuild Iraq’s mental health delivery capabilities and USAID’s psychosocial programs in Afghanistan. Diwan interviewed Afkhami in early March to get his views of the Covid-19 virus, particularly as relates to Iran.

Michael Young: Why has the Covid-19 pandemic hit Iran so hard?

Amir Afkhami: A combination of economic, political, and ideological motives is responsible for the rapid and large-scale Covid-19 outbreak in Iran. The pandemic’s advent was predictable due to China’s status as Iran’s principal commercial partner. But the Iranian government’s inadequate precautionary measures to restrict and monitor travelers from China ensured that the disease would make landfall in Iran much more quickly than in any other country of the Middle East.

Tehran’s lack of transparency and unwillingness to take robust measures, such as social distancing and quarantines, particularly at the epicenter of the outbreak in Qom, helped spread the virus shortly after it arrived. Iran’s battered economy likely contributed to Tehran’s mismanagement of the crisis. This included inadequate preparations for the eventuality of an outbreak, most evident in the shortage of domestically produced facemasks and personal protective equipment in the country as late as last month. This was due to Tehran’s unwillingness to restrict Iranian exports to China and the authorities’ bewildering opposition to travel restrictions and quarantines for fear of further harming the economy.

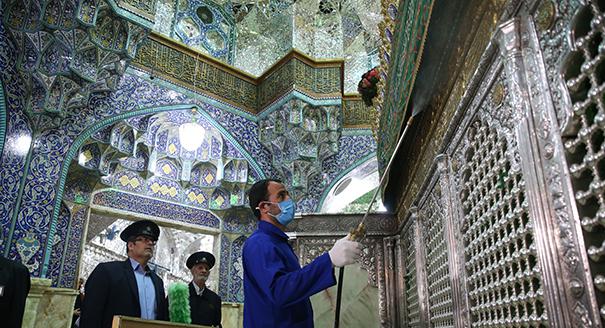

In all likelihood, politics also played a role in minimizing the leadership’s public health response. It sought to ensure a large turnout for the country’s parliamentary elections, which the supreme leader, ‘Ali Khamenei, had billed as a religious duty. The unwillingness of the religious strata in the country to place restrictions on pilgrimages and assemblies in major Shi‘a shrines worsened the growing crisis. The Iranian government’s desire to project an image of competence and control, especially as it sought to restore its diminished reputation after the downing of a civilian jetliner last January, likely drove it to double down on some of these policies, even as Covid-19 cases, and fatalities, grew. This only added fuel to the fire.

MY: Some have speculated that the impact of the virus could have a profound effect on Iran, even predicting it could extend to politics. How realistic is such a view?

AA: From a historical perspective, this is a very real possibility. In 1904, the inability of Iran’s absolutist Qajar government to respond to a cholera pandemic, and the resulting social and economic consequences, led directly to the 1906 Constitutional Revolution, which established a parliamentary system of government. At that time, much of the discontent centered on the fact that cholera, like epidemics in general, was much better controlled in Western countries than in Iran. This leads me to believe that the long-term political impact of the current Covid-19 outbreak will partly depend on how Iranians perceive the performance of neighboring countries and the West in addressing the pandemic. The short-term consequences, in the way Covid-19 has eroded public trust in the government and worsened Iran’s economy, are already evident.

MY: There are reports that Iranian officials have been taken to Lebanon for treatment in Hezbollah-run hospitals. What do you see as the reasons for this?

AA: Iran has some of the best physicians and most advanced hospitals in the region. It hosts thousands of medical tourists every year and its officials enjoy preferred access to the country’s healthcare facilities. Therefore, it would be very unusual for Iranian officials to be taken to hospitals in Lebanon. That is unless they were already in the area or the aim was to hide the full impact of the pandemic on Iran’s aging leadership, which has been particularly hard hit due to higher mortality among the old and those whose immunity is compromised.

MY: The coronavirus has shown that something infinitely small can have an impact that is infinitely large and can affect the global economy. Do you feel that this will lead to a change in the behavior of states, and if so in what direction?

AA: I think that the biggest impact internationally will be on driving the modernization of our vaccine development and production process into one that is more responsive, flexible, and scalable so as to stop viral outbreaks such as the coronavirus or influenza before it reaches pandemic proportions. Among other changes, this will involve moving away from the slower 1950s-era egg-based vaccine production system, which dominated the market, to a production method involving recombinant DNA technology which can produce vaccines within a matter of weeks.

MY: Where do you see the coronavirus pandemic going in the coming months?

AA: The pandemic will increase and it is conceivable that most adults around the world will get the virus over the next twelve months. However, the pace of growth and the resulting stress on healthcare infrastructures will depend on the robustness and efficacy of detection and prevention measures in each country.