A recent offensive by Damascus and the Kurds’ abandonment by Arab allies have left a sense of betrayal.

Wladimir van Wilgenburg

{

"authors": [

"Michael Young"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Diwan",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [

"Reaction Shot",

"Decoding Lebanon"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "menaTransitions",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center",

"programAffiliation": "MEP",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Levant",

"Lebanon",

"Middle East"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform"

]

}

Source: Getty

Spot analysis from Carnegie scholars on events relating to the Middle East and North Africa.

What Happened?

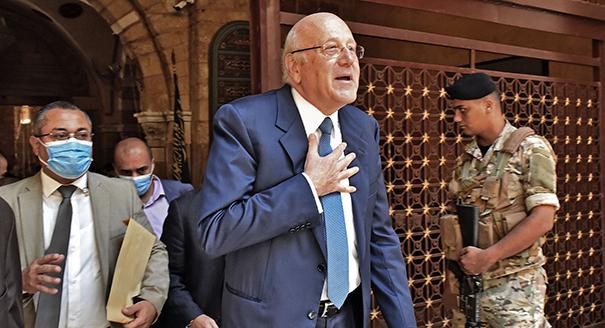

After more than a year of waiting, Lebanon has a new government. The new prime minister, Najib Mikati, succeeded where his two predecessors, Mustapha Adib and Saad al-Hariri, failed. President Michel Aoun and Mikati signed the official documents after last-minute efforts to remove the final obstacles that had blocked the process, including who would become economics minister and who would be the two Christian ministers not aligned with Aoun and his son in law Gebran Bassil. This last point was important as it denied the two men a sufficient number of ministers in the cabinet of 24 to hold veto power over the agenda, as well as the latitude to bring it down in the event of a collective resignation of their ministers.

Why Is It Important?

While it’s early to speculate what cut the Gordian Knot, the fact that Aoun and Bassil do not appear to have the ability to block decisions in the cabinet, therefore to control its functioning or its life, suggests that Bassil may have been obliged to compromise. Many analysts argued that he had relentlessly sought control over the new government in order to use this as leverage to succeed Aoun, who leaves office next year. Without such power, Bassil’s presidential ambitions may be thwarted. That’s unless he feels he somehow has sway over the two Christian ministers who are seen as independents. This would give him the means to force them to resign and bring the government down, thereby using the ensuing vacuum to blackmail the political class into endorsing him as president.

Media reports in Beirut suggested that one major factor forcing Bassil to back down was the strong pressure exerted on him from Hezbollah and Iran. Both were reportedly displeased with the fact that Bassil’s brinksmanship was causing a deterioration in Lebanon that was provoking a backlash against Hezbollah, particularly within the Shia community. That may be true, but the fact that Bassil’s bloc in parliament will reportedly vote confidence in the government suggests that things may be more complicated than that.

Bassil was caught in a dilemma. Had he blocked a government, this would have pitted him and Aoun against the entire political class, which wants a government, as well as made Aoun the prime target of public anger for the remainder of his term. The worsening economic situation, not to say chaos, would have made it all but impossible for Bassil to make a move on the presidency. Perhaps he reasoned that it was better to try his luck with a government in place, than to try building his presidency on the shifting sands of an impoverished country in which state control is rapidly diminishing.

The cabinet also represents a success for Mikati, who would very much like to remain in office beyond the parliamentary elections scheduled for next spring, if they take place. When Hariri gave up on forming a government weeks ago, he had hoped to use Sunni anger against Aoun as a means of winning support in the elections. But now Mikati has changed the narrative. If he can slow down Lebanon’s collapse and improve the daily lot of citizens, many Lebanese may focus less on an electoral clash and more on the decisions the cabinet will take to make their miserable situation better. If one had to identify a loser in the process, it is probably Hariri, who is not overly pleased to see Mikati take the office he had wanted for himself.

What Are the Implications for the Future?

The first thing the government will try to do is arrest Lebanon’s perilous economic decline. After the formation was announced, the Lebanese pound gained in value, trading at LP15,750 against the U.S. dollar, after trading at LP18,150 = $1.00 in the morning. This means that the purchasing power of the population, 74 percent of which lives in poverty, will immediately rise. Mikati also announced that subsidies would be brought to an end. While this will lead to inflation, the move will be accompanied by the distribution of ration cards in U.S. dollars to 500,000 of the country’s most vulnerable families. The lifting of subsidies is expected to end the hemorrhaging of Lebanon’s remaining foreign currency reserves. It should also bring an end to the long lines for gasoline and fuel that have plagued Lebanon in recent months, as subsidized fuel, which is held by a cartel of distributors, was deviated to Syria where prices are higher

Beyond immediate relief, Mikati must begin discussions with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) over a bailout package. The prime minister has been in touch with IMF officials in recent weeks, and would like to move quickly on that front. But even before then, the fact that a government is in place will mean that Lebanon will be able to use hundreds of millions of dollars that have been pledged to the country, including $546 million in World Bank loans (of which $246 million have already been approved for an emergency social safety net for the poor) and $370 million in humanitarian aid pledged at an August 4 donor conference in Paris. Lebanon is also expected to receive very soon around $860 million from the IMF, which is the country’s Special Drawing Rights allocation.

Mikati’s priority is to revive the electricity sector, the bleeding wound of the economy. The state now supplies one or two hours of electricity a day, on average, forcing people to rely heavily on private generator owners who charge market prices for fuel, which is excessively expensive for most consumers. The economic opportunity cost is also immense, as countless companies and businesses have closed down or reduced working hours due to shortages in electricity. Most importantly, the availability of fuel will allow Lebanon’s hospitals to function, as many had warned they might close down over the absence of fuel supplies to operate their generators.

Politically, there are many minefields ahead. Gebran Bassil still wants to become president and this may very well affect cohesion in the cabinet if he decides to order the ministers he named to block unpopular government decisions so he can gain favor. Without a sense of common purpose in the cabinet, Mikati’s plans may be derailed, so the prime minister will have to be agile in managing his differences with the president and his son in law to avoid deadlock. But for now, the Lebanese will breathe a sigh of relief. They have received only bad news for two years, and now may see some light, albeit a very pale light, at the end of the tunnel.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

A recent offensive by Damascus and the Kurds’ abandonment by Arab allies have left a sense of betrayal.

Wladimir van Wilgenburg

Israeli-Lebanese talks have stalled, and the reason is that the United States and Israel want to impose normalization.

Michael Young

The government’s gains in the northwest will have an echo nationally, but will they alter Israeli calculations?

Armenak Tokmajyan

Beirut and Baghdad are both watching how the other seeks to give the state a monopoly of weapons.

Hasan Hamra

The country’s leadership is increasingly uneasy about multiple challenges from the Levant to the South Caucasus.

Armenak Tokmajyan