Mohanad Hage Ali

{

"authors": [

"Mohanad Hage Ali"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Diwan",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [

"Reaction Shot"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "menaTransitions",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center",

"programAffiliation": "MEP",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Levant",

"Iraq",

"Middle East",

"Iran"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform"

]

}

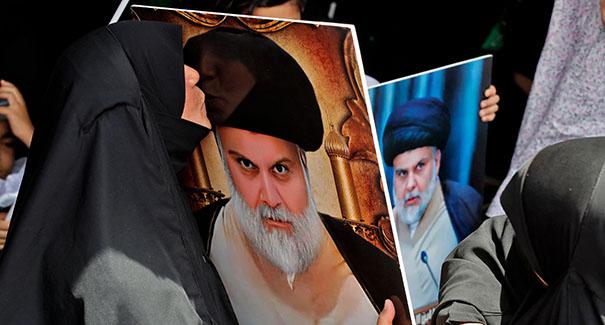

Source: Getty

Muqtada al-Sadr Has Announced His Withdrawal From Politics

Spot analysis from Carnegie scholars on events relating to the Middle East and North Africa.

What Happened?

In yet another of his unpredictable political maneuvers, on August 29 Shiite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr announced his withdrawal from politics. This prompted his loyalists to clash with rival Shia groups and storm a government complex in Baghdad’s so-called “Green Zone.”

Sadr’s move came in reaction to criticism directed against him by his Iran-based former mentor, Grand Ayatollah Kadhim al-Haaeri, who is considered a successor to Sadr’s late father, Mohammed Sadeq al-Sadr, who was assassinated by Saddam Hussein’s regime in 1999. On the same day, Haaeri also announced his resignation from his clerical role, and asked his adherents, including Sadr’s supporters, to accept Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, as their source of emulation. What was particularly notable was that he did not ask his followers to accept Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, who is based in the Iraqi city of Najaf and is a more senior cleric than Khamenei, as their source of emulation.

In his resignation letter, Sadr hinted that Iran could have been behind Haaeri’s resignation and criticism of him, before declaring that he would withdraw from politics and shut down most of his institutions. He had previously hinted at such an announcement after failing to translate his win in the parliamentary elections of October 2021 into the formation of a government, because his Shia foes had joined forces to oppose him. Nor is this Sadr’s first withdrawal from political life. In 2008, he had left Iraq to study under Haaeri in Iran, and in 2014 he had also withdrawn from politics, only to reverse himself later.

Why Is It important?

First, on the political level, Sadr’s resignation and the possibility of expanded violence will widen the chasm between Sadr and his Shia foes who are close to Iran. The era of Shia unity and consensus-building in politics is dying and will be difficult to repair. Sadr’s exit from politics, which follows his bloc’s mass resignation from parliament last June, highlights the impotence of a political system in the presence of armed and powerful nonstate actors. This is particularly true of the Popular Mobilization Forces, an umbrella organization of armed militias, many of which are led by, or include, Sadr’s Shia rivals.

Violence, as demonstrated in the clashes on August 29, is a very real possibility. And as Prime Minister Mustapha al-Kadhimi warned earlier this month, if bullets are fired the fighting might not end for years. Because avenues of change and mobility from within Iraqi state institutions are closed, and because peaceful demonstrators have been severely repressed, violence may emerge as the most likely alternative, given that popular dissatisfaction will look for an outlet.

Second, for Haaeri to be thrust into the political battle in Iraq—by Iran, Sadr hinted—represented another level of intervention, and is important not only in relation to Sadr but also to the standing of Najaf’s seminaries in the Shia world. Haaeri’s shifting his followers’ source of emulation to Khamenei was timely, as the question of the 92-year-old Sistani’s succession reemerged last year following the death of Mohammed Said al-Hakim, another senior cleric in Najaf and once a potential successor to Sistani. However, what is at play is not a simple Qom vs. Najaf or Iran vs. Iraq standoff, given the clergy’s diversity, but the Iranian regime’s hegemony or leadership over a historically multipolar and institutionalized religious realm. Such diversity has often had political consequences or manifestations.

Since Iran’s revolution in 1979, the clerical regime has continued to try and merge political and religious leadership in the supreme leader’s position. While Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was a grand ayatollah, a source of emulation (marjaa al-taqlid) with uncontested religious credentials, Khamenei, a former Iranian president who spent much of his life in politics rather than engaging in religious scholarship, was suddenly elevated to the rank of senior cleric following the death of Iran’s then highest-ranking cleric, grand ayatollah Mohammed al-Araki in 1994. In the 1970s and 1980s, Khomeini was only second to grand ayatollah Abou al-Qassem al-Khoei, as opposed to Khamenei whose religious credentials were contested. Haeri’s endorsement of Khamenei, whether it was coerced or voluntary, could be Tehran’s attempt to contain Sadr, but perhaps is also a case of Iran’s flexing its muscles in the much more significant matter of playing a role in determining Sistani’s successor in Najaf. This could explain why Sadr responded to Haaeri’s instructions by saying “Holy Najaf is the highest source of emulation,” which implied that it was not Khamenei’s Iran that could pretend to play such a role.

What Are the Implications for the Future?

Sadr’s announcement, like his bloc’s withdrawal from parliament, showcases the limitations of state institutions, elections, and parliamentary arithmetic in places where armed nonstate actors compete for power. Sadr may be erratic, but he is also still manageable for Iran and its interlocutors. The challenge for Iran lies in the growing disenchantment among segments of Iraq’s Shia populations with Tehran’s allies, who have failed to govern adequately. Should the mounting grievances of Sadr’s supporters set the ground for wider violence, his volatile behavior and his followers’ lack of discipline and training might well backfire against the Sadrist movement, causing him to lose popular support.

Sadr’s withdrawal from the political scene, even if it is temporary, could also beg the question of whether the Coordination Framework, the grand coalition of the cleric’s adversaries, can still hold together. Without Sadr as an adversary, this hodgepodge of Shia politicians and factions, even if most are Iranian allies, might break apart, further complicating efforts to form a new government.

About the Author

Deputy Director for Research, Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center

Mohanad Hage Ali is the deputy director for research at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center.

- Is Türkiye Lebanon’s New Iran?Commentary

- An Automated Occupation in South LebanonCommentary

Mohanad Hage Ali, Mohamad Najem

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Diwan

- Axis of Resistance or Suicide?Commentary

As Iran defends its interests in the region and its regime’s survival, it may push Hezbollah into the abyss.

Michael Young

- U.S. Aims in Iran Extend Beyond Nuclear IssuesCommentary

Because of this, the costs and risks of an attack merit far more public scrutiny than they are receiving.

Nicole Grajewski

- Iran and the New Geopolitical MomentCommentary

A coalition of states is seeking to avert a U.S. attack, and Israel is in the forefront of their mind.

Michael Young

- Kurdish Nationalism Rears its Head in SyriaCommentary

A recent offensive by Damascus and the Kurds’ abandonment by Arab allies have left a sense of betrayal.

Wladimir van Wilgenburg

- All Eyes on Southern SyriaCommentary

The government’s gains in the northwest will have an echo nationally, but will they alter Israeli calculations?

Armenak Tokmajyan