Michael Young

{

"authors": [

"Michael Young"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Diwan",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "menaTransitions",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center",

"programAffiliation": "MEP",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Levant",

"Israel",

"Palestine",

"Middle East",

"North America",

"United States"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform"

]

}

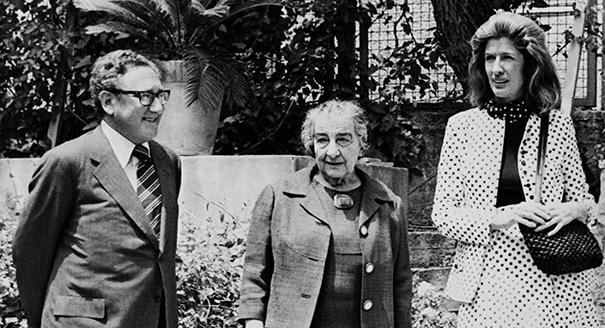

Source: Getty

Fabricated Facilitator

Despite claims to the contrary, few countries have undermined UN resolutions on Arab-Israeli peace more than the United States.

Last week, the Columbia University professor Rashid al-Khalidi published an article in the New York Times in which he described how the United States planned to build a new embassy in Jerusalem, on land seized by Israel from Palestinians.

Khalidi condemned the U.S. plan for solidifying “Israel’s exclusivist claims to the city, whose permanent status is one that the United States itself and the international community agree remains to be determined.” He went on to write that this was another example showing how “U.S. opposition to Israel’s settlement enterprise and expropriation of Palestinian land has never been more than rhetorical. For decades, Washington has bemoaned Israel’s behavior while remaining complicit in its colonization by providing the country with more than $3 billion in military aid every year, much of which is used to oppress Palestinians.”

Khalidi’s pro-Israel critics would no doubt bristle at such a phrase. However, few countries have done more to undermine the foundational United Nations resolution that ended the June 1967 Arab-Israeli war—in which Israel occupied the West Bank, East Jerusalem, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Golan Heights—than the United States. If Israel’s supporters are offended, that’s because nothing hurts like the truth. Security Council Resolution 242, which imposed an equation of “land for peace,” opened by reaffirming “the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war.” It called for the “[w]ithdrawal of Israel armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict.” This was one of the conditions defined by the resolution as necessary for “the establishment of a just and lasting peace in the Middle East.”

Since 1967, the clause on withdrawal has divided Israel and the Arab world. In the English version of the resolution, Israel succeeded in leaving the scope of the territories “occupied in the recent conflict” indefinite. Had the wording specified “the territories occupied in the recent conflict,” this would have implied a withdrawal from all the lands Israeli seized then, but the article “the” was left out. This allowed for an interpretation that Israel did not have to pull out of all the territories it had occupied, but only unspecified territories. This linguistic legerdemain only applied to the resolution’s English version. Israel showed foresight in grasping that the English interpretation would prevail, even though it was contradicted by the resolution’s rendition in other languages.

While this semantic debate is well known, what many people recall less is how the United States, between 1970 and 1972, only reinforced Israel’s interpretation, the end result of which was to empty Resolution 242 of much of its meaning. Far from just being complicit in Israel’s settlement enterprise, Washington trashed the diplomatic basis denying that enterprise’s legitimacy. To add insult to injury, it did this to a UN resolution Washington had been instrumental in drafting.

The American steps on this path were hardly linear, as different administrations, even the same administration, brought separate ideological perspectives on the Arab-Israeli conflict to the table, creating a cacophony of views. In December 1969, the Nixon administration presented what became known as the Rogers Plan, named for William Rogers, the secretary of state at the time. The plan reaffirmed Resolution 242, but inserted a caveat that there might have to be border adjustments to occupied Arab land that Israel would return, as the borders prevailing before the 1967 war were defined by the armistice agreements of 1949, therefore were not necessarily final borders. However, the United States viewed these adjustments as minor, underlining that it did not support expansionism.

However, Rogers was not the real mover on foreign policy at the time. President Richard Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, were, and took steps to grind down the Rogers Plan, which both quietly opposed. In a July 1970 letter to Israel’s then prime minister, Golda Meir, the administration promised her that the United States would not insist on Israel’s accepting the Arab definition of Resolution 242. This anodyne phrase meant the Americans did not consider that the resolution mandated a full withdrawal from the lands occupied in 1967.

In February 1972 the administration went further, affirming that Israel need not commit itself to a full withdrawal from the occupied territories as part of any interim agreement with the Arabs. This meant that Israel could enter into such negotiations without their ultimate outcome being set beforehand, leaving Israel with a wide margin of diplomatic maneuver.

Most important, the Americans and Israelis agreed that Washington would not make any moves on Middle East peace without first discussing them with Israel. In other words, Israel was provided with effective veto power in this regard.

These undertakings were concluded bilaterally, but their impact has blocked UN decisions indefinitely. This was particularly true when the Trump administration decided, in December 2017, to formally acknowledge Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, and, in March 2019, to recognize Israel’s annexation of the Syrian Golan Heights. The Biden administration, despite trying to differentiate its policies from those of Donald Trump, has done nothing to reverse either of his rulings. It has blithely ignored that Washington, with other members of the UN Security Council, had opposed Israel’s 1981 annexation of the Golan, characterizing it in Resolution 497 as “null and void,” before demanding that Israel “rescind” its decision.

In that context, while one can understand Khalidi’s frustration, for the United States to build an embassy on occupied Arab land is hardly a break with past behavior. In the last 56 years, Washington has portrayed itself as the grand purveyor of Middle Eastern peace, while gainsaying countless times its stated positions on the requirements of a settlement. It has also helped one party, Israel, impose all its preferences on Arabs and Palestinians, most recently by concluding separate peace agreements with Arab states. That is why, even if no comprehensive peace is achievable without America, none can actually be reached through America.

About the Author

Editor, Diwan, Senior Editor, Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center

Michael Young is the editor of Diwan and a senior editor at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center.

- Iran and the New Geopolitical MomentCommentary

- A Mechanism of CoercionCommentary

Michael Young

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Diwan

- U.S. Aims in Iran Extend Beyond Nuclear IssuesCommentary

Because of this, the costs and risks of an attack merit far more public scrutiny than they are receiving.

Nicole Grajewski

- What Gaza Showed UsCommentary

The conflict did not reshape Arab foreign policy; on the contrary it exposed its limits.

Angie Omar

- The Jamaa al-Islamiyya at a CrossroadsCommentary

The organization is under U.S. sanctions, caught between a need to change and a refusal to do so.

Mohamad Fawaz

- Iran and the New Geopolitical MomentCommentary

A coalition of states is seeking to avert a U.S. attack, and Israel is in the forefront of their mind.

Michael Young

- Kurdish Nationalism Rears its Head in SyriaCommentary

A recent offensive by Damascus and the Kurds’ abandonment by Arab allies have left a sense of betrayal.

Wladimir van Wilgenburg