Implementing Phase 2 of Trump’s plan for the territory only makes sense if all in Phase 1 is implemented.

Yezid Sayigh

{

"authors": [

"Michael Young"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Diwan",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [

"Palestine: The Wars in the War",

"Reaction Shot"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Lebanon",

"Israel"

],

"topics": []

}

Spot analysis from Carnegie scholars on events relating to the Middle East and North Africa.

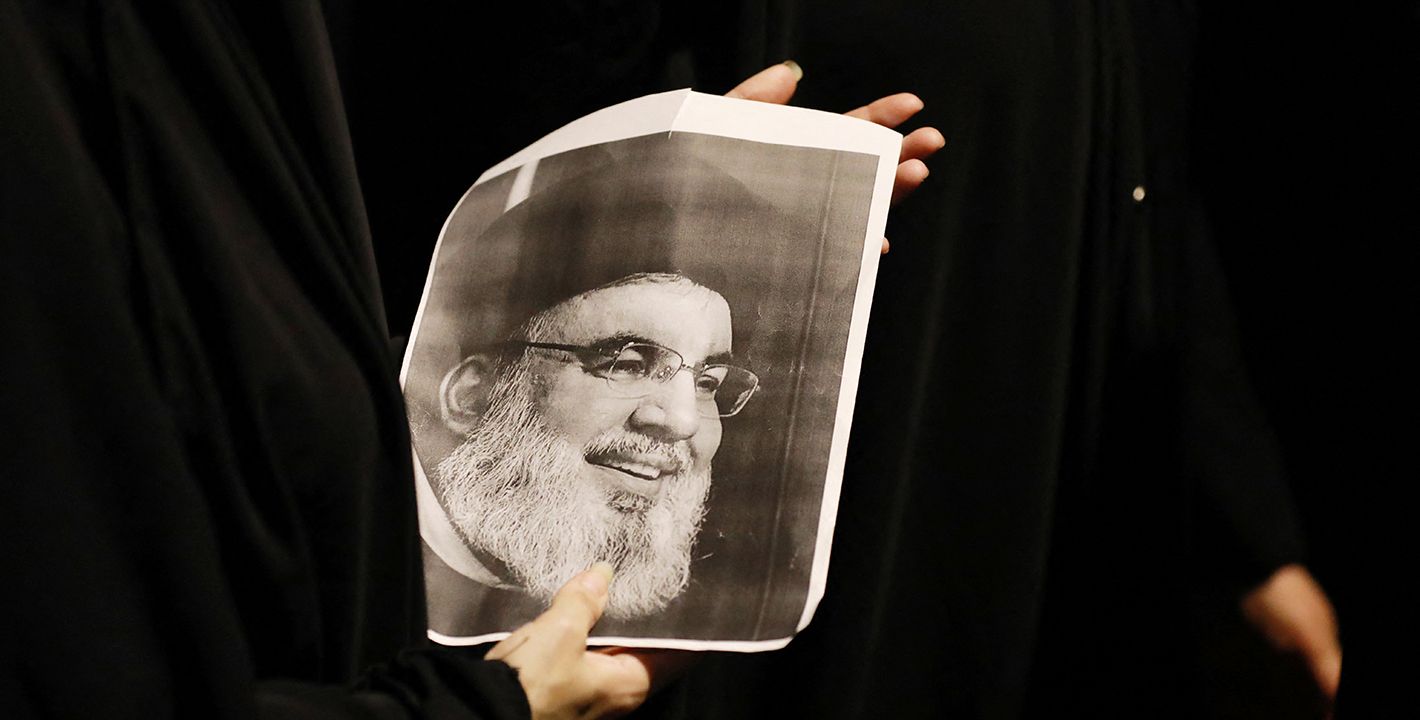

On September 27, Israeli aircraft bombed what the Israelis described as Hezbollah’s central headquarters, located under residential buildings in the Haret Hreik quarter of Beirut’s southern suburbs. The aircraft reportedly used bunker buster bombs to kill the secretary general of Hezbollah, Hassan Nasrallah, who was said to be in a facility under the buildings. On September 28, Hezbollah confirmed that Nasrallah had been killed. The same day, Lebanon’s Health Ministry put the casualty toll at 33 killed and 195 injured, yet this included not only those killed or injured in the operation against Nasrallah (numbers that many observers expect will increase in the coming days), but also victims of subsequent night-long Israeli airstrikes against the southern suburbs.

According to initial reports, one of those also killed in the attack was Ali Karaki, Hezbollah’s commander for south Lebanon. Karaki had been the target of an Israeli attack on September 23, which failed. Media sources close to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps announced that a senior IRGC general, Abbas Nilforushan, was a victim of the attack as well. According to the U.S. Treasury Department, he was deputy head of operations for the IRGC.

By killing Nasrallah, the Israelis showed a willingness to escalate the conflict in Lebanon to unprecedented levels. The secretary general was only the latest in a long line of senior Hezbollah officials, mainly senior and mid-level military commanders, who were assassinated by Israel in the war that the party launched on October 8 of last year. His death showed, not for the first time, that Israel has managed to deeply infiltrate Hezbollah’s ranks, and has been repeatedly aware of the time and place of high-level meetings, or simply the location of the party’s leadership.

It is conceivable that the Israelis may believe that now is a good time to initiate an invasion of part of southern Lebanon. With the Hezbollah leadership in disarray, there could be less resistance by the party to any deal worked out with the Lebanese government. Their rationale may be that if they occupy land, they can then exchange any withdrawal from Lebanon for reinforced security arrangements along the Lebanese-Israeli border, since Security Council Resolution 1701, which brought an end to the war of 2006 and governs relations in the border area, doesn’t have an enforcement mechanism to prevent Hezbollah combatants from returning to the border. The Israelis may presume that Nasrallah’s absence gives Lebanon’s government more leeway to negotiate. Yet it seems unlikely that Beirut would agree to be put in a position where it is seen as a defender of Israel’s borders, against Hezbollah.

The big question is how Iran will respond to the risk that its principal regional ally, Hezbollah, may be routed in the conflict with Israel. The Iranians have said that Nasrallah’s killing will be avenged, but there are constants in their behavior that are unlikely to be reversed. Since the bombing of Iran’s embassy in Damascus last April, followed by the assassination of Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran in July, and culminating in Nasrallah’s elimination, the Iranians have regarded such Israeli actions, probably correctly, as traps to provoke a war between Iran and the United States. Iran’s president, Masoud Pezeshkian, implied this in comments this week, when he said Iran would not fall into the “trap” of a regional war.

In light of this, two outcomes seem more probable: First, that Iran will avoid entering the fray directly, but will use its regional allies to retaliate for Nasrallah’s killing in a coordinated way, while ensuring this remains within confines that do not invite U.S. intervention. And second, that it will continue to prevent, or largely prevent, Hezbollah’s use of the precision-guided missiles Iran gave to the party, but whose deployment Tehran apparently controls, to target Israeli infrastructure and population centers, as these missiles ultimately serve to defend Iran against U.S. or Israeli attacks.

If this assessment is correct, Nasrallah’s death may not lead to an all-out regional war, while even a major escalation by Hezbollah in Lebanon is very risky for the party. Hundreds of thousands of Shia are now internally displaced, and large areas of Shia habitation in southern Lebanon, the Beqaa, and Beirut’s southern suburbs have been completely devastated. Any escalation of the war, supposedly on Gaza’s behalf, will only senselessly increase the destruction, while being highly unlikely to restore Hezbollah’s impaired deterrence capability. It may also serve to increase the frustration and anger among Hezbollah’s suffering coreligionists.

If the outbreak of a regional war is not necessarily in the cards, and Hezbollah’s latitude to escalate the war from Lebanon is limited by Iranian restrictions, many eyes will be turned to the domestic Lebanese scene to see what happens. Hezbollah is isolated at home, as many Lebanese have opposed the opening of a southern front against Israel, on top of their own communal reasons for resenting the party. This has given rise to a situation that may severely constrain Hezbollah’s margin of maneuver and complicate the ability of any new secretary general to impose himself as the party’s legitimate leader following the charismatic Nasrallah.

Two logics impose themselves today, as Lebanon reels from the war with Israel: a logic of resistance and a logic of the state. The logic of resistance affirms that the conflict against Israel must continue in support of Gaza, under the rubric of what is known as the Unity of the Arenas strategy. This strategy holds that the different members of the pro-Iran Axis of Resistance must coordinate their actions and come to each other’s defense whenever one member is attacked.

However, the logic of the state also imposes itself on a country that has been carried into a catastrophe by an armed group that has disregarded the Lebanese state. This logic supports bolstering state institutions and ending the anomaly of a country governed by a non-state actor. Many people believe that the single national institution that retains credibility and widespread popular endorsement is the Lebanese army. Whereas the logic of resistance leads to support for Hezbollah’s favored candidate, Suleiman Franjieh, as president of the republic, with Hezbollah portraying him as the person best able to defend the resistance, the logic of the state leads to the election as president of Joseph Aoun, the armed forces commander. The army reassures most Lebanese by playing a vital role in maintaining stability, at a time of profound uncertainty, and is expected to be crucial in negotiations over security arrangements in the south that would end the conflict with Israel.

Standing at the center of these two contradictory approaches is one man: Nabih Berri, the speaker of parliament. As the most senior Shia official in the Lebanese state, and the only head of a governing national body that is not vacant or operating in a caretaker capacity, Berri is the axis around which Lebanon’s branches of government are now operating. Therefore, he will be essential in determining which of the two logics—resistance or the state—prevail.

If Berri decides to support the logic of resistance in order to protect his ties with Hezbollah, the outcome may harm him. The Shia community has been ravaged by Israel’s onslaught, so supporting a continuation of the war may only weaken the community further, thereby weakening Berri himself. On the other hand, if Berri supports the logic of the state, he would be essential to bringing any new president to office. He has long preferred Franjieh, whose election seems a near impossibility today, so if a consensus coalesces around Joseph Aoun, the speaker may go along with this in order to preserve his centrality in the system. His backing would also be needed to persuade Hezbollah to accept a compromise.

Yet it’s entirely possible that any new Hezbollah secretary general would be even more intransigent on Franjieh than Nasrallah was, mainly because he will have to prove himself equal to his predecessor. But standing up against Berri may not be easy, especially for a less experienced figure, if the speaker pushes in a particular direction. Ultimately, Berri may choose to do nothing, but that would only deepen the dilemma in which Hezbollah finds itself: The party refuses to end its support for Gaza, because doing so would risk a backlash from an outraged Shia community demanding to know what its sacrifices were for. But continuing a war in which Hezbollah is at a decisive disadvantage would only lead to more destruction of Shia areas, and perhaps of Lebanon as a whole. In that case, the party would face the rage of a community, even a county, that would see such a decision as justification alone to question Hezbollah’s ruinous hegemony.

Implementing Phase 2 of Trump’s plan for the territory only makes sense if all in Phase 1 is implemented.

Yezid Sayigh

Israeli-Lebanese talks have stalled, and the reason is that the United States and Israel want to impose normalization.

Michael Young

Beirut and Baghdad are both watching how the other seeks to give the state a monopoly of weapons.

Hasan Hamra

The country’s leadership is increasingly uneasy about multiple challenges from the Levant to the South Caucasus.

Armenak Tokmajyan

Recent leaks made public by Al-Jazeera suggest that this is the case, but the story may be more complicated.

Mohamad Fawaz