Stéphane Malsagne is an author and a professor of history at Sciences-Po in Paris. He is the author of several books, including Fouad Chéhab, Une Figure Oubliée de l’Histoire Libanaise (Karthala, 2011), Sous l’Œil de la Diplomatie Française: Le Liban de 1946 à 1990 (Geuthner, 2017), and, co-authored with Dima de Clerck, the forthcoming Le Liban En Guerre: De 1975 à Nos Jours, an updated version of a book published in 2021. Diwan interviewed Malsagne in late February to discuss his biography of Fouad Chehab.

Michael Young: Your book is a fascinating and much-needed biography of Fouad Chehab, Lebanon’s president between 1958 and 1964. But might I start with a disagreement? The subtitle of your book is “Une figure oubliée de l’histoire libanaise,” or “a forgotten figure in Lebanese history.” Yet not only is Chehab far from forgotten in Lebanon, many Lebanese often seem to be in perpetual anticipation of the return of a Chehabist figure. In using this subtitle, what were you trying to say?

Stephane Malsagne: The biography of Fouad Chehab, published in 2011, is the result of my doctoral research, in which I sought to fill a significant historiographical gap in the life and legacy of this prominent Lebanese reformist political figure. At the time of its publication, there was no scholarly biography of Chehab available in English, French, or Arabic, which prompted me to undertake my research. While numerous scholars have drawn parallels between Chehab and Charles de Gaulle, the relevance of such a comparison is exaggerated. Nevertheless, the purpose of this study was to explore the reasons for Fouad Chehab’s enduring prestige and popularity among the Lebanese people.

In the absence of comprehensive biographies until the early 2000s, Fouad Chehab remained an overlooked Arab leader in academic research and was virtually unknown to Western audiences, particularly in France, where my book was published. In this biography, I argue that Fouad Chehab (1902–1973) cannot be reduced to Chehabism, a term that designates the period of his reformist presidency (1958–1964) and whose spirit persisted under his successor Charles Helou (1964–1970). Chehab’s personal career offers a unique vantage point from which to examine the major events and issues that have shaped modern Lebanese history, from the period of the French Mandate to the eve of the civil war in 1975.

A second reason for the title of the book is related to the Lebanese people’s perception of their own history. Many people still believe that the golden age of Lebanon and the myth of the “Switzerland of the Middle East” are much more closely associated with the presidency of Camille Chamoun (1952–1958), when banking secrecy was established in Lebanon (1957), than with that of his successor, Fouad Chehab (1958–1964). On the contrary, my biography seeks to emphasize that the golden age lies elsewhere, in the first attempt during Chehab’s presidency to build a modern state in Lebanon based on modern institutions, social justice, and a policy of development of underdeveloped peripheral areas. Most Lebanese, with the exception of the younger generations, knew Fouad Chehab, but I found during my research that many of them had little or no knowledge of the importance of the institutional and social reforms launched under his presidency with the help of the French IRFED mission, led by Dominican Father Louis-Joseph Lebret. In fact, this crucial period in Lebanese history is not taught in Lebanese schools today and is still not well studied in the curriculums of the various universities in Lebanon.

Thanks to new and unpublished sources with which I had an opportunity to work, I offered a much more nuanced analysis of this reformist moment, so that the Lebanese people could rediscover their own history. Chehab’s legacy has left a dual image in current Lebanese narratives: that of a president who carried out important reforms and tried to short-circuit the sectarian system; but also that of a president who violated freedoms and established an authoritarian regime through the officers of the army’s famous Deuxième Bureau, or military intelligence agency, especially after the failed coup of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) in 1961. Although the Deuxième Bureau undoubtedly interfered in the electoral processes during the 1960s, I showed that this reputation was part of a conspiratorial narrative of Fouad Chehab, largely constructed by his opponents, both Christian and Sunni Muslim. After Chehab’s death, it is true that many politicians and reformist elites in Lebanon claimed his legacy and sought to bring the issue of state reform and social justice to the forefront, including during the civil war (1975–1990). After the war, references to Chehab and his reformist policies returned regularly to the Lebanese political scene, especially when elected presidents, like Chehab himself, came from the military institution. We saw this again recently with the election of General Joseph Aoun.

MY: As you ended your book, what were the main conclusions you reached about Chehab, and do you feel another Chehab is possible in the present Lebanese context?

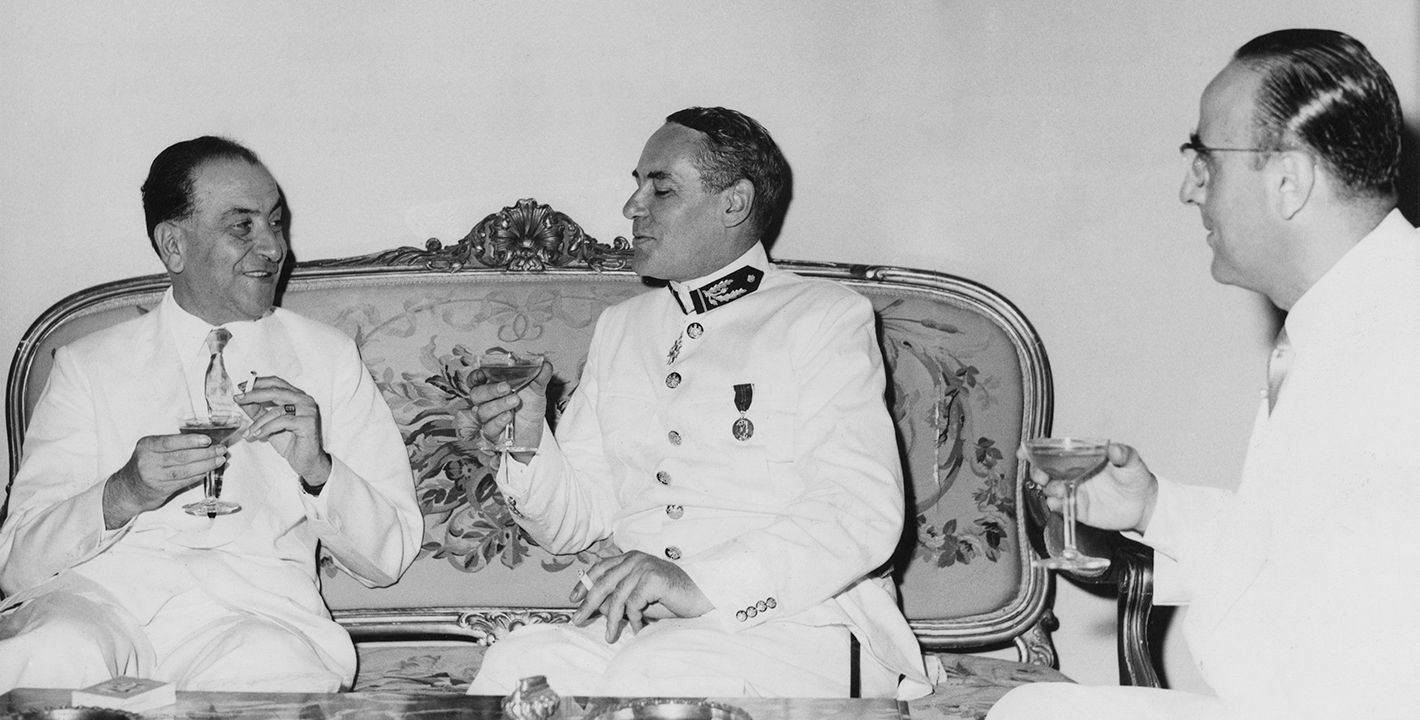

SM: My biography makes it clear that Fouad Chehab scorned the Lebanese political class. He thought his country was paralyzed by political confessionalism and the patronage games of what he called the “fromagistes,” or those who shared the “cheese” of state among themselves. Moreover, Chehab was never attracted to power or the preservation of power. As commander of the armed forces, he first refused to run for president in 1952, despite repeated requests. In 1958, in the midst of the first Lebanese civil war, he reluctantly agreed to run at the last minute because his name had been the subject of a consensus between the Egypt of Gamal Abdel Nasser and the Americans. Witnesses even report that after his election in July, the bells in his village of Kisirwan rang the death knell. During his presidency, he accomplished his mission of restoring order and launching a series of reforms of the country and its administration. In July 1960, he announced that he would resign from the presidency. Under pressure from members of parliament, and probably his wife, he finally agreed to reverse his decision. But this display of contempt for power was unprecedented in the history of independent Lebanon. In 1964, he refused to extend his term, although many encouraged him to do so.

As president and an admirer of Charles de Gaulle, Fouad Chehab tried to develop the image of an honest and pious president who lived a simple life and refused wealth and honors. His main themes were the general interest, the unity of the Lebanese, national independence, social justice, and the sovereignty of his country. Chehab wanted to offer a counter-model to the political class of his country.

Second, he was unwavering in his belief that strict adherence to the Lebanese constitution was paramount to Lebanon’s stability. However, he was strongly reluctant to engage in the practice of political and administrative appointments based on sectarian affiliation, which he saw as a major obstacle to the country’s development. This attitude was exemplified by his famous statement of August 4, 1970, in which he declared that he could not run for the presidency again unless the constitution was reformed. At that time, he knew full well that this was impossible. He recognized that efforts to implement reforms were likely to face opposition from conservative forces who sought to maintain their privileges. By challenging political confessionalism, Chehab failed. However, he proved to be a visionary, because these issues are being taken up today by a younger generation of reformists, who have understood that this was a major factor in the paralysis of reform in Lebanon.

Comparing the Chehab presidency to the present is not only premature, but also historically an irrelevant approach. The contexts are totally different and historians must avoid this pitfall. It is unwise to speak of a new Chehab in 2025 in relation to Joseph Aoun, as some have done. There are some similarities, including the fact that both are former commanders of the armed forces and were elected in a context of war after a consensus among regional and international powers (Egypt and the United States in 1958, and the United States and its Arab allies, including Saudi Arabia, taking advantage of the weakening of Hezbollah in 2025). Many Western observers saw Chehab and see Aoun as providential men. But the comparison ends there. Many Lebanese are no longer calling for a providential man; they made it clear during the protests of 2019 that they wanted a president capable of initiating reforms.

In 1958, Chehab’s election took place in parliament without a foreign army. This was unlike 2025, when the Israeli army shelled and destroyed a large part of Lebanon, especially the south and the southern suburbs of Beirut, causing numerous deaths among Lebanese civilians, and a large number of displaced, while occupying part of the south. Nor was Chehab elected in the presence of foreign ambassadors who had come to offer their support, as in 2025 for Joseph Aoun, who was congratulated in front of the cameras by U.S., French, and Arab representatives, creating the impression of a weak president under the direct control of the West and dependent on Western financial aid to carry out reforms. It is also noteworthy that before assuming the role of president, Joseph Aoun served as commander of a military that was both weak and humiliated. This military was completely incapable of protecting the country from Israeli bombardment. Given his limited military resources, it is likely that Chehab’s performance would have been similar.

At the beginning of his term, at the end of the 1958 crisis, Fouad Chehab encountered a regional environment that exhibited a greater degree of stability than today. This facilitated the implementation of reforms supported by the majority of antagonistic political parties. These parties were previously gathered in a “no victor, no vanquished” government following the minor civil war of 1958.

Chehab’s foreign policy of strict neutrality was also a strategic move to assuage the internal dissensions associated with an orientation deemed too Western for Muslims, as evidenced during Camille Chamoun’s presidency, or too pro-Arab for Christians, as demanded by the Nasserite factions. This diplomatic approach paid considerable dividends, providing Lebanon with nearly six years of relative stability despite the failed coup by the SSNP in 1961. This stable environment facilitated the consideration of long-term reforms aimed at establishing a modern state based on the principles of state reform, social justice, and harmonized territorial development.

In the current context, it seems that the aforementioned conditions for an independent reform policy accepted by all Lebanese are not currently in place due to a very unstable external environment. Israel continues to occupy five locations inside Lebanon, despite the provisions that provided for its complete withdrawal from the country, and the Israeli army continues to regularly violate Lebanese sovereignty by sending drones to bomb so-called Hezbollah positions. In addition, Western (mainly American) and Israeli pressures on the Lebanese government are very strong and do not contribute to stability. The Shia are under pressure and feel targeted by the new alliance between President Joseph Aoun and Prime Minister Nawaf Salam. Instead of a policy of “no victor, no vanquished,” the Lebanese government, under American and Israeli supervision, has been ordered to reduce Hezbollah’s influence as much as possible or risk losing financial aid. The Lebanese government has even had to ban air travel between Beirut and Tehran. Despite the loss of its main leaders, eliminated by Israel, and the deployment of the Lebanese army in the south, Hezbollah, which is attached to its prerogatives, retains a significant military arsenal and continues to exert its influence by weighing on the policies of the government, which proclaims itself as reformist. It is too early to say whether this government will succeed in implementing such reforms.

MY: There is an interesting sociological dimension in Chehab, who was from a noble family. Normally, such people don’t enroll in the military, but because Chehab’s father disappeared when Fouad was young and the family was cash poor, he appears to have joined the army out of financial necessity. How did this shape the man?

SM: The army deeply shaped Fouad Chehab’s personality and career. Although he belonged to an illustrious Maronite family whose ancestor, Bashir II, was emir of the Mountain in the 19th century, Fouad joined the army after the World War I for economic reasons. His family, originally from the Kisirwan, suffered greatly from the war. Before World War II, he was sent to French military schools for training. His potential as a leader was quickly recognized by French officers, and in 1945 he became the founding father of the Lebanese army (Ab al-Jaysh), a role the military institution in Lebanon continues to honor to this day. His time in France left an indelible impression on him, fostering a deep bond with France and a strong Francophile sentiment that would guide his political decisions during his presidency from 1958 onward. Upon returning to Lebanon, Chehab ascended the ranks in the “Troupes Spéciales du Levant,” a unit led by French officers.

At that time, two things left a mark on him: his encounter in Lebanon at the end of the 1920s with Charles de Gaulle, who impressed him profoundly and served as his political role model for life, although Chehab never officially met his mentor during his presidency. A second thing was that, as a young officer, Chehab was involved in securing the territories of the French Mandate in Lebanon by fighting against banditry. There, he became keenly aware of the state of underdevelopment in which many Sunni and Shia communities in the outlying regions of northern and southern Lebanon and the Beqaa Valley lived. The army made Chehab aware of social and developmental issues in Lebanon. Many Lebanese Muslims, neglected by the successive governments in place since Independence, did not recognize themselves as Lebanese in the state created by France in 1920. A large part of the Lebanese periphery had no roads, schools, electricity, or water.

This context is essential for understanding the 1958 uprising led by Muslim leaders from these regions against Camille Chamoun. Chamoun was accused of violating the National Pact through his pro-Western policies and of having favored Beirut and Christian Lebanon to the detriment of Muslim regions. Chehab, the armed forces commander in 1958, defiantly refused to obey Camille Chamoun’s orders to use the army to suppress what the Chamoun called at that time the “rebels.”

The Lebanese army’s neutrality during the 1958 events was essential for pacifying the country and establishing Fouad Chehab as the consensus candidate for the presidency, a position that the opposing camps accepted. Chehab demonstrated an unwavering commitment to maintaining this neutrality throughout his career. He understood that the key to strengthening the unity of his country and reinforcing Lebanese identity was not only neutrality in foreign affairs, but also embarking on an ambitious policy of developing outlying regions, which he initiated during his time in office. Chehab founded and led the armed forces as a model and mirror of society. The military institution, under his leadership, was set up as a shining example of unity, citizenship, courage, and hard work. However, the army also ended up unintentionally contributing to the conspiratorial narrative of Chehabism when officers during and after his presidency were accused of interfering in political games to support Chehabist candidates. Chehab has always maintained that he himself did not encourage such interference.

MY: How would you qualify Chehab’s reform efforts during his term? What kind of a new elite did it create, who drove the president’s reforms, and were these successful?

SM: At the start of his term, Chehab initiated a series of reforms, the first of which was administrative reforms implemented by décret-loi, or decree, in 1959 with the objective of enhancing the efficiency of the Lebanese state. New structures were created, some of which are still in place today, including the Civil Service Council, which aims to recruit more competent civil servants to serve the state, and a Statistical Institute with the objective of collecting precise data on the conditions of the Lebanese economy and society. The concept of fortifying and rationalizing the state through the implementation of a statistical apparatus and a flexible planning policy represented a novel approach in Lebanon, where elites had historically favored the merchant republic and economic laissez-faire since the country’s independence in 1943.

The second major strand of reforms pertained to regional economic development, which entailed opening up outlying areas of the country through road construction, the electrification of remote villages, the establishment of drinking water supply systems, and the development of village schools.

Chehab entrusted this development policy to a Ministry of Planning created under Chamoun, but whose prerogatives were strengthened from 1959 onward. The ministry collaborated closely with the French IRFED mission, to which Chehab had entrusted a pivotal role at the highest echelons of the state. This mission, comprising French and Lebanese experts, was tasked in 1959 with assessing the needs of the populations and the possibilities for development in Lebanon’s peripheries. In 1960, the mission published a widely cited report that revealed the significant economic and social inequalities between a minority of the population, who held the bulk of wealth, mainly around Beirut, and a large impoverished Shia Muslim population that was completely cut off from this island of prosperity. The report also concluded that it was necessary to develop productive sectors, such as agriculture and industry, that were underrepresented in Lebanon’s GNP compared to the services sector. Concurrent with the IRFED mission, Lebanon promulgated a Social Security Code in 1963, based on the French model, laying the foundations for a welfare state.

The main innovation of the Chehab presidency was an unprecedent desire to promote meritocracy within the state at the expense of traditional recruitment based on sectarianism and patronage, which favored the traditional political families, or zu‘ama. On the contrary, Chehab tried to promote technocrats as the core of a new political elite within the state, one based primarily on skills. Many of them were Muslim engineers, who, for the first time in Lebanese history, occupied large number of key posts in the state. Indeed, Chehabism represents the first golden age for Lebanese engineers in the state, most of them trained abroad, as well as for foreign experts whom the state called upon in all fields to modernize the country.

This Lebanese technocracy, which I have studied in detail, occupied strategic positions in various public offices (a true parallel administration in which the logic of sectarian recruitment no longer applied), in the general directorates of the ministries, and even in the presidency, where Chehab was advised by a brain trust. Some of these individuals even became president of Lebanon, such as Elias Sarkis during the 1975–1990 civil war. Others tried to revive the spirit of the Chehabist reforms, including during the civil war and during the reconstruction of Lebanon after 1990.

The outcome of these Chehabist reforms must be qualified. The current Lebanese state undoubtedly owes an important part of its institutions to Chehab. Let us not forget that the National Council for Scientific Research, which recently provided a detailed assessment of the major destruction caused by Israel in 2025, was created by Fouad Chehab. The regional development policy launched in the 1960s opened up and provided electricity to many villages and developed irrigation and the agricultural sector. However, state intervention did not succeed in rebalancing Lebanon’s productive sectors. Chehab also faced resistance from local leaders and the Maronite Church, who saw state intervention in regional development as a threat to their privileges and prerogatives. Some of Chehab’s reforms were abandoned under the presidency of Charles Helou, and the technocratic elites imposed by Chehab failed to assert themselves against the politicians. The construction of roads to open up peripheral regions accelerated the exodus of impoverished Shia from the south to the southern suburbs of Beirut at the end of the 1960s, reinforcing their political radicalization on the eve of the civil war. This is a paradox of Chehabism that my colleague Dima de Clerck and I highlight among the factors leading to the civil war in our book, Le Liban En Guerre: De 1975 à Nos Jours, which will appear in March, as an updated version of the book we published in 2021.

MY: You also address in your biography the post-1964 period, when Chehab was no longer president, but Lebanon was going through major upheavals, with fighting in the south between the Palestinians and Israel, culminating in the 1969 Cairo Accord. If you had to summarize Chehab during this period, what was most striking about him?

SM: After 1964, Chehab officially retired from political life, but he remained influential, as many people came to consult him on the evolution of the situation in the country. Although he had not been commander of the armed forces since 1958, his prestige within the Lebanese military remained very strong. Under the Helou presidency, allegations of intervention by the Deuxième Bureau in electoral politics in favor of Chehabist candidates multiplied, but Chehab always maintained that these were abuses and that he did not condone these practices. In the second half of the 1960s, he was very concerned about developments in his country, as some of the economic reforms he had initiated were abandoned under pressure from conservative forces.

His second concern was the growing polarization of Lebanese society and political life, as well as the increase in violence due to the growing weight of the Palestinian factor after the June 1967 war. Chehab was disillusioned by the end of his life. In a letter written in 1965, he predicted the possibility of a new civil war in Lebanon, which did break out ten years later. Regarding the Palestinian question, he considered the Palestinian cause and the armed struggle of the Palestine Liberation Organization as legitimate, but he refused to allow the PLO to establish itself in Lebanon to carry out its military operations against Israel in order to preserve Lebanese unity. He clearly expressed his rejection of the 1969 Cairo Agreement signed by then armed forces commander, General Emile Boustani.

MY: Finally, as we touched on earlier, Lebanon has a new president, Joseph Aoun, who is perceived by some people as following in the footsteps of Fouad Chehab (rightly or wrongly, we shall soon see). As you examine what you call the myth surrounding Chehab and its repercussions and reverberations, does it tell us anything about the kind of challenges that the current president is likely to face?

SM: Immediately after his election, some analysts and even part of the Lebanese media, were quick to present the new president as a strong president and the right man for the job, even before he had managed to carry out any reforms. We have already seen the particular circumstances of his election. The same thing happened in 1958 with Fouad Chehab, who became the man of the moment immediately after the mini-civil war. However, Chehab had a free hand to rapidly launch an ambitious reform program without international pressure, and without having to deal with the existence of a powerful military force in the country, such as Hezbollah, which many describe today as a state within a state. Nor did he have to face an Israeli army that is violating Lebanese sovereignty on a daily basis with its warplanes and drones. It is this very point that lends itself to the argument that a comparison between Chehab and Aoun is ultimately irrelevant. At the end of his presidency, Chehab had earned the title of reforming president and statesman because he had a real political balance sheet that was to his advantage. His decisions were made easier by his neutrality in foreign policy and independence from the great powers. Despite the United States’ support for his election, he did not align himself with Washington, instead opting to rely on France’s assistance in developing his country.

Some efforts may already be underway to fashion the myth of Joseph Aoun. However, the lack of tangible measures to quickly revitalize Lebanon, without excluding any community for political reasons (Shia are a current example), could make turn this into a mere facade. Aoun’s ability to maneuver independently, unhindered by pressure from Donald Trump’s new administration in the United States and blackmail over Western financial aid, seems limited at this stage. Only time will tell us whether Aoun will be brave enough to stand up to Washington and live up to the myth that some are already trying to create for him.