Beirut and Baghdad are both watching how the other seeks to give the state a monopoly of weapons.

Hasan Hamra

{

"authors": [

"Yezid Sayigh"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Diwan",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Palestine",

"Israel"

],

"topics": [

"Foreign Policy",

"Security"

]

}

Or how the absence of insights about the Israeli “other” is a hindrance for the Palestinian liberation struggle.

Palestinians and (Jewish) Israelis are locked in a strange and damaging paradox. Majorities on both sides don’t really know the other, and yet seemingly believe they do with absolute certainty, as people dedicated to the complete annihilation of the other.

In Israel, knowing the Palestinians, especially those who found themselves under military rule in the first seventeen years after Israel’s establishment in 1948, was overwhelmingly the domain of the military intelligence and domestic security services, and of a handful of academic “Arabists,” who advised the authorities. Only a few Israelis, most prominently members of the joint Jewish-Arab Communist Party, could claim to “know” Palestinians for any purpose other than controlling them.

On the opposite side, as Jonathan Gribetz details in his most recent book, Reading Herzl in Beirut: The PLO Effort to Know the Enemy, learning about the Israeli Other was a primary purpose of the Research Center established in 1965 by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Gribetz is a professor in the Near Eastern Studies Department and in the program in Judaic Studies at Princeton University. His interest derives from his previous book, Defining Neighbors: Religion, Race, and the Early Zionist-Arab Encounter, which studied “how Arabs and Zionists in Palestine and the broader region conceived of one another in the final decades of Ottoman rule.” This revealed that Muslim Arabs recognized that “the return to Zion was central to the Jewish religious tradition,” while Zionists acknowledged “the close similarities between Judaism and Islam and the long history of generally amicable relations between Jews and Muslims in the Levant” (p. xii). Indeed, “certain Arab intellectuals in the region argued that the economic, social, and cultural success of Jews in Europe demonstrated that Semites were no less capable than European races and thus, that as the Jews’ racial relatives, Arabs were equally able to excel in these areas” (p. xiii). Astonishingly, the Zionist leader who went on to become Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, “believed that Palestine’s Arab peasants were not merely the Jews’ racial relatives but themselves bona fide Jews in racial terms.” (p. xiii).

But in 1965, “the political encounter between Zionists and Arabs was profoundly different, almost unrecognizably so.” By then, knowing the enemy was contentious terrain. The same is true again today, 60 years later. Gribetz’s new book looks at one angle of what happened in between, and at why it’s important. He is a historian, and a nontheoretical one at that. His tone is judicious, balanced, and empirically neutral. And yet he employs the tools of ethnography to bring into clear focus the individuals involved not only in establishing the Research Center, but also in shaping its scholarly and political legacy. The narrative that Gribetz unfolds across 278 pages is wonderfully empathetic: it neither obscures nor exceptionalizes things such as the Palestinians’ perceptions or the circumstances of being driven from their homes in the course of Israel’s establishment. His deep dive into the political thought of the center’s founders and researchers, and into the cultural and ideological influences to which it was subject, therefore delivers a powerful human story.

I emphasize this because the history that Gribetz tells is so personal to me: Fayez Sayegh, the Research Center’s founder, and Anis Sayegh, who became its director in 1966, were both my paternal uncles. I was not quite a teenager when the center was founded, but its subsequent trajectory was interwoven with my own political development and, no less so, my humanist values. What struck me most on reading Gribetz’s book was the extraordinary intertwining of the threads he teases apart with those from which the tissue of today’s seemingly apocalyptic confrontations is spun: antisemitism, anticolonialism, and knowing the Other/Oneself. Neither Gribetz nor his publishers could have realized that his book would appear amid the extreme polarization generated by the Hamas attack of October 7, 2023, and the Israeli war on Gaza. However, it is timely to be reminded of the “radical” fact that six decades ago the PLO, in the form of its Research Center, thought it important and necessary to study Zionist texts and Jewish history.

One of the most important outcomes of this interest was the publication by the Research Center of a lengthy indictment by Asaad Razzouq of “European antisemitic myths and conspiracy theories about the Talmud” and their relationship with Zionism (p. 106). TheTalmud and Zionism debunked the fraudulent Protocols of Elders of Zion and argued for the repudiation and elimination of antisemitism—all this in Arabic, for Arab audiences, not as propaganda for Western ones. Indeed, the Palestinian Authority’s Ministry of Culture published an online version of Razzouq’s book in 2009.

Gribetz concludes that the Research Center’s engagement with “Judaism and core Jewish texts” in order to argue against antisemitism constituted “a critical legacy of the Center” (p. 122). The center’s effort appears all the more extraordinary in hindsight, given the current weaponization of the fight against antisemitism by governmental and university authorities—including by frankly antisemitic rightwing politicians and movements—in various Western countries who repeatedly deploy the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism as “a blunt instrument to label anyone an antisemite,” in a statement by the IHRA’s author, Kenneth Stern. The performance of liberal virtue is used cynically to cloak the silencing of dissent about Palestine and collusion in the mainstreaming of Islamophobia and anti-migrant racism, and to justify a wholesale onslaught on academic freedoms.

The actual readership of such scholarly output on Judaism and Zionism was probably small. I confess that what I appreciated the Research Center for most was its Shu’un Filastiniyya (Palestinian Affairs) periodical, that started life as a quarterly and then became a monthly, and which reached a large audience of Palestinians and other Arabs. It was especially through Shu’un Filastiniyya that the center achieved what Gribetz labels “bidirectionality,” connecting academic research to the political purposes of the PLO and intellectual engagement to activism. He cites the “pioneering programmatic article” by leading PLO figure Salah Khalaf, who used Shu’un Filastiniyya to set out the argument for recognition of pragmatic realities and an embrace of diplomacy following the Arab-Israeli war of October 1973. This was the first public step in a trajectory that eventually culminated in the PLO’s espousal of a two-state solution to the Palestine conflict and its formal recognition in 1988 of Israel’s right to exist. Khalaf was arguing for something that Anis Sayegh steadfastly opposed to the end of his days, but it was his commitment as editor of Shu’un Filastiniyya to free debate and intellectual integrity that established the periodical as the arena for all Palestinian political factions and ideological currents to debate issues dividing them deeply.

There is not enough space here to do more than note some issues that Gribetz examines. One is PLO chairman Yasser Arafat’s tense relationship with Anis Sayegh and with the Research Center more generally (which Anis discussed in his autobiography), leading to the temporary detention of the late Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury, who edited Shu’un Filastiniyya in 1975–1979. This antagonism may also help explain the sorry fate of the center’s archive: initially seized by Israeli forces when they entered West Beirut in September 1982—concurrently with the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps massacre by Israeli-assisted rightwing Lebanese militias—it was returned to the PLO as part of a prisoner exchange deal. However, Arafat banished it to a PLO camp in Algeria, where it eventually disappeared.

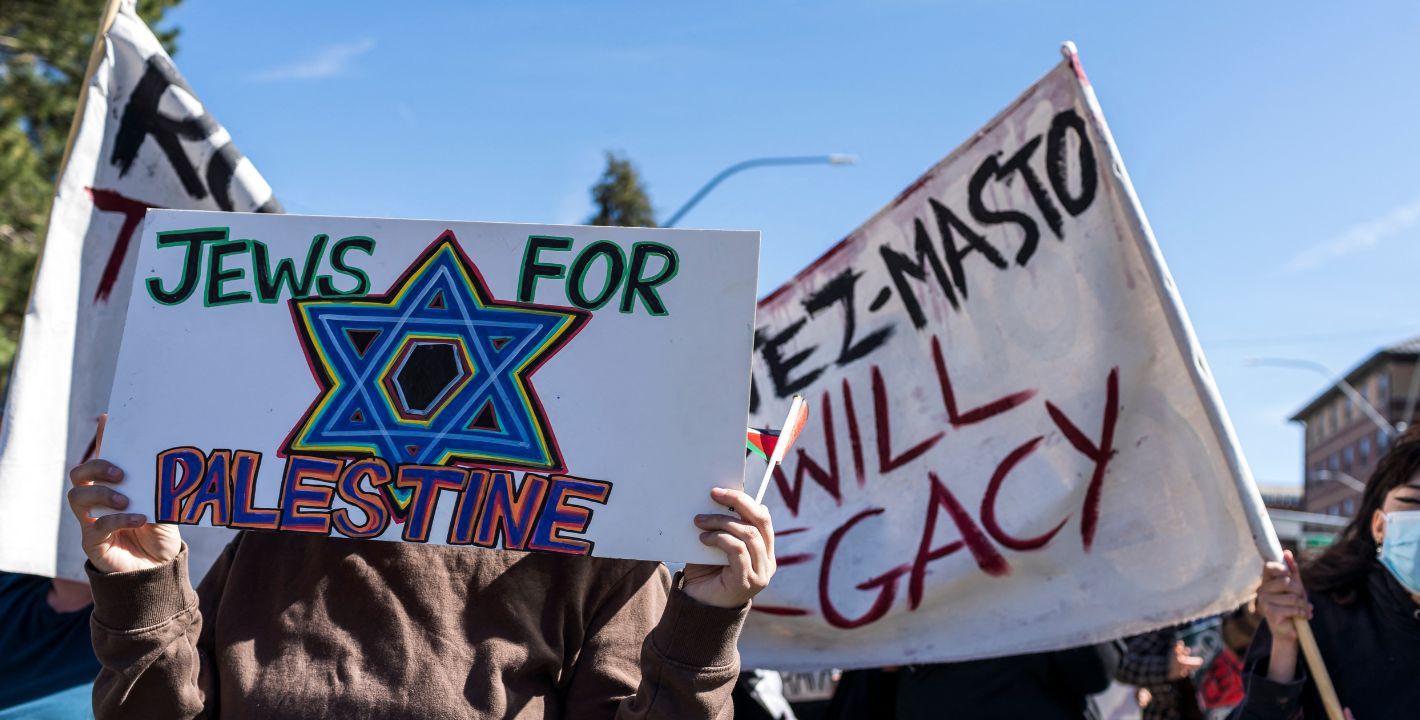

More pertinent for our present day are three issues that Gribetz raises, which are once more of vital concern to a Palestinian movement that is again struggling to find its way. First, in addition to opposing antisemitism, the Research Center sought to ground its views in the attitude of those non- or anti-Zionist Jews, especially in the United States, who were always “deeply unsettled by Israeli policies toward both the Palestinian refugees and Arabs living under Israeli rule,” in the words of the American journalist Peter Maass. This partly reflected Fayez Sayegh’s engagement with U.S. Jewish organizations in the 1950s and 1960s, which Geoffrey Levin has recently explored in Our Palestine Question, at a time when “leaders of mainstream American Jewish organizations stated very clearly that anti-Zionism was not inherently antisemitic.” Gribetz carries the theme forward, arguing that “[a]s the debate over the nature of Jewishness persists into the twenty-first century, and as the implications of the definition of Jewishness appear no less weighty, new and perhaps similarly peculiar convergences and coalitions may be on the horizon” (p. 136).

Second, as Gribetz notes, “the PLO Research Center’s gaze was also on the global community.” Specifically, he argues that the center perceived international law as important to frame arguments, impacting “the PLO political leadership’s decision to engage in global diplomacy” (p. 4). The institutional infrastructure of international law has in fact proved disastrously wanting in the face of genocidal violence over the past decade—in Myanmar, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and now Gaza—prompting disillusionment among many Palestinians and their global supporters. Yet others, such as Bashir Abu-Manneh, still regard international law as the crucial “universal standard for justice that has to sit at the core of an emerging Palestinian liberation strategy.” As Lori Allen shows in her book A History of False Hope: Investigative Commissions in Palestine, this replicates a century-long pattern of Palestinians repeatedly seeking justice and protection from an international legal framework that has just as often let them down.

Lastly, it is refreshing to recall the influence of Fayez Sayegh, who, in the words of Yoav Di-Capua, cited by Gribetz, “persistently deployed an existentialist perspective to elucidate the impact of the colonial condition on the Arab subject” (p. 16). This evokes the path of his contemporary, Martinique revolutionary Frantz Fanon, which is painstakingly traced in Adam Shatz’s The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon. Indeed, it is hardly coincidental that both men have been rediscovered by a new generation of activists, who now circulate Fayez’s observations on decolonization in his article “Zionist Colonialism in Palestine,” published by the Research Center in 1965, alongside Fanon’s various writings on colonialism. Recognizing both the condition of the colonial subject and the abomination of antisemitism is a bridge for solidarity. It is in this context that the IHRA definition is being wielded as a tool to suppress not only Palestinians but also Jewish dissenters from Israeli policies and practices. Genuine solidarity, conversely, addresses the continuing, crucial intertwining of Palestinian and Jewish fates as discussed in the On the Nose podcast titled “Talking About Antisemitism,” for example.

My uncle Anis once told me about the resistance he initially met among Palestinians and Arabs opposed to the center’s intention to study all things Israeli. Yet this was the precursor to a fairly long line of “Israeli studies” programs established in Arab countries since then. When I recently sought insight through social media on the changing ideological profile of the Israeli officer corps, one response was “they are all Zionists, it makes no difference.” Anis, who was maimed by a Mossad letter bomb in 1972 and who again demonstrated his anti-Zionist credentials as spokesperson of the alliance of rejectionist factions opposed to the PLO’s 1993 Oslo Accords with Israel, would have been unimpressed, to put it mildly. True to his mission for knowledge, Anis invited me to speak to his Palestinian Cultural Forum, made up of Palestinians residing in Beirut, about my impressions of the Israeli officers I had met as a peace negotiator.

Israel has changed beyond recognition since the PLO Research Center first set out to study its politics, government, society, and economy. However, too much of “knowing the enemy” has been hijacked by the likes of Yahya Sinwar and other Hamas “graduates” of Israeli prisons who claimed to understand their enemy well. The slaughter of civilians in southern Israel by their fighters on October 7, 2023, shows they did not. Instead, it conveyed a dearth of the understanding that the PLO Research Center and Shu’un Filastiniyya pioneered. Palestinians may and do legitimately disagree among themselves, but the fact that there are no longer enough gatekeepers willing to host cantankerous debate and accept contestation in good faith in the manner that those precursors once did is a calamitous hindrance to their struggle.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Beirut and Baghdad are both watching how the other seeks to give the state a monopoly of weapons.

Hasan Hamra

The country’s leadership is increasingly uneasy about multiple challenges from the Levant to the South Caucasus.

Armenak Tokmajyan

The U.S. is trying to force Lebanon and Syria to normalize with Israel, but neither country sees an advantage in this.

Michael Young

The objective is to lock Hamas out of political life, but the net effect may be negative indeed.

Nathan J. Brown

The negotiator will have a delicate task of preserving Lebanon’s eroding sovereignty and getting on with Nabih Berri.

Michael Young