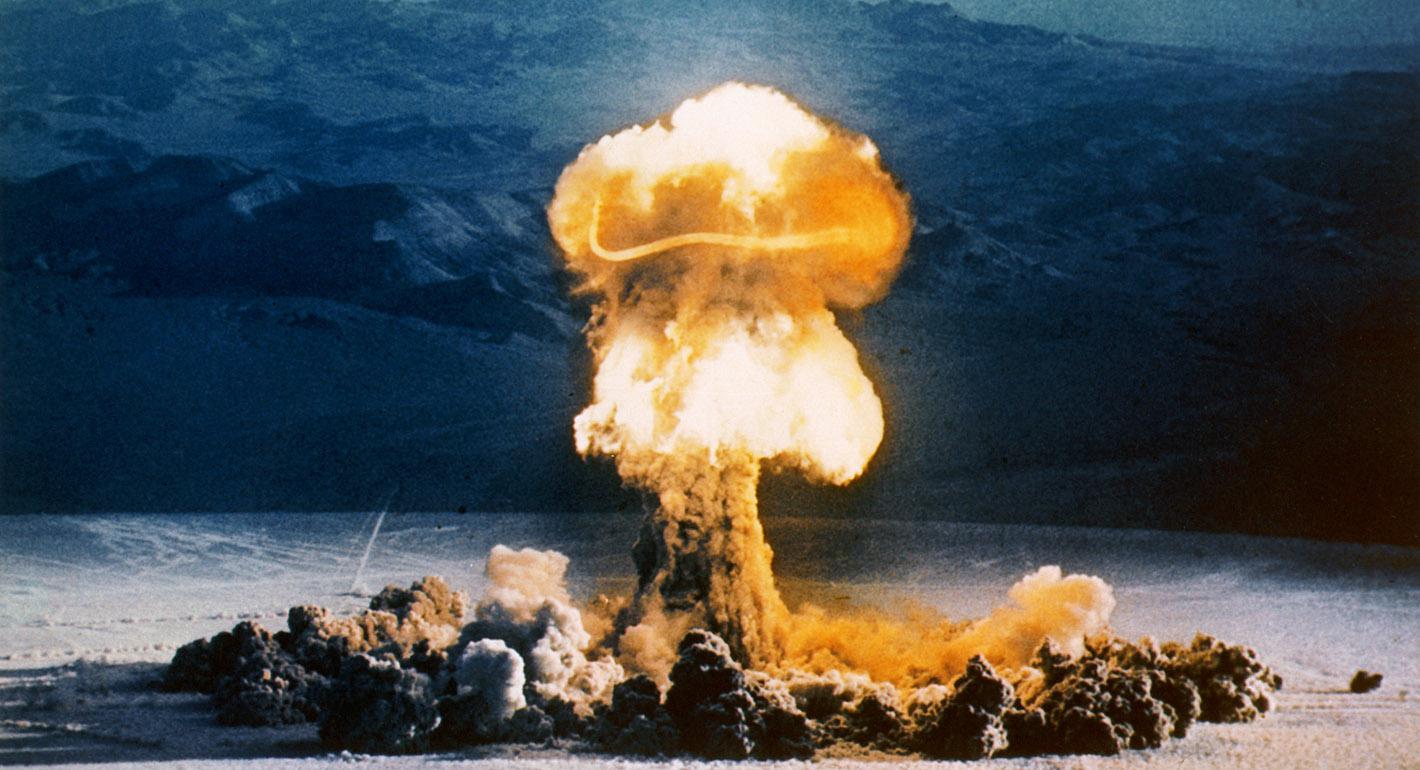

Россия отзывает ратификацию Договора о всеобъемлющем запрещении ядерных испытаний (ДВЗЯИ) — одного из ключевых международных соглашений в сфере глобальной безопасности. Владимир Путин, а вслед за ним и остальные российские чиновники утверждают: речь идет о восстановлении паритета с США, которые до сих пор не ратифицировали ДВЗЯИ. Между тем плюсы для Москвы от такого шага неочевидны. А вот негативных последствий может быть немало.

Претензии России

Более двух десятилетий Россия пыталась сделать ДВЗЯИ, открытый к подписанию еще в 1996 году, одним из компонентов стратегического диалога с США. 4 июня 2000 года Владимир Путин и Билл Клинтон подписали Заявление о принципах стратегической стабильности, где среди прочего упоминался вопрос ратификации документа. Россия пошла на этот шаг 30-го числа того же месяца, а вот США все медлили, что сделало ДВЗЯИ удобным инструментом для давления на Вашингтон.

Российские эксперты регулярно говорили, что целесообразно было бы восстановить паритет. Такие заявления звучали и на фоне выхода США из Договора 1972 года об ограничении систем ПРО, и в рамках переговоров по ЕвроПРО в начале 2010-х, и гораздо позже. Стремление сохранить стратегический паритет и «повести себя зеркально» в отношениях с Соединенными Штатами в итоге и стало обоснованием нынешней дератификации Россией ДВЗЯИ.

Путин вспомнил об этом договоре еще в феврале, выступая перед Федеральным собранием. Он заявил, что «некоторые деятели в Вашингтоне» задумываются о возможности натурных испытаний ядерного оружия. Судя по словам президента, его беспокоит разработка ядерной боеголовки W93, информация о которой впервые появилась в бюджетном запросе Минэнерго США в феврале 2020 года. Тогда же американская администрация заявила о возможном возобновлении ядерных испытаний. В США давали понять, что испытания могли бы подвигнуть Китай присоединиться к соглашениям по сокращению стратегических вооружений.

Однако то была администрация республиканца Дональда Трампа. Соратники демократа Джо Байдена, наоборот, выступают в поддержку ДВЗЯИ и обещают добиваться вступления договора в силу. В 2021 году, уже после смены команды в Белом доме, сотрудник Лос-Аламосской лаборатории Чарли Накле подтвердил, что W93 можно поставить на вооружение и без натурных ядерных испытаний, которых так опасался Путин. Так что российские власти в своей риторике как будто обращаются к прошлому правительству США. Или готовятся к возможной победе республиканцев на выборах-2024.

Слова Путина соответствуют устоявшемуся среди многих российских специалистов мнению, что создание нового типа боезаряда обязательно требует натурных ядерных испытаний. Об этом говорили в том числе академики Александр Сахаров и Виктор Михайлов. Однако это представления в лучшем случае из середины 2000-х. Современная наука позволяет разрабатывать новые боеголовки без полномасштабных испытаний.

МИД России также беспокоит принятое в США «решение о повышении готовности ядерного испытательного полигона в Неваде». Однако в 2018 году российские дипломаты уже жаловались, что американцы повысили до шести месяцев степень готовности полигона к возобновлению полноформатных ядерных испытаний. Прошло уже пять лет, полноформатных испытаний там по-прежнему нет, а претензии все те же.

Нынешняя активность на полигоне связана с субкритическими ядерными и неядерными экспериментами, которые не запрещены ДВЗЯИ. Это не означает, что США готовы провести там ядерные испытания хоть завтра. Более того, такая же активность наблюдается на ядерных полигонах в Китае и самой России. Научный руководитель российского ядерного центра ВНИИЭФ Вячеслав Соловьев признавал, что Центральный ядерный полигон России на архипелаге Новая Земля готов к возобновлению ядерных испытаний. Дело лишь в политической воле.

Другие участники

В том, что ДВЗЯИ не вступил в силу, российский МИД винит только США. Действительно, американские власти подписали договор в 1996 году, но до сих пор не ратифицировали его — прежде всего из-за нежелания связывать себе руки в вопросах национальной безопасности. Однако дело не только в позиции США. Согласно условиям договора, для его вступления в силу нужна ратификация 44 странами, имеющими ядерное оружие или возможности его создания (этот список определен Международным агентством по атомной энергии). Помимо США, есть еще семь проблемных стран. Египет, Израиль, Иран, Китай подписали договор, но не ратифицировали его. А Индия, КНДР и Пакистан даже не дошли до подписания.

Не приходится ожидать, что ратификация ДВЗЯИ Соединенными Штатами станет стимулом для этой семерки. Индия и Пакистан, например, больше смотрят друг на друга, чем на США. Показателен и пример России. Ратификация ею договора в 2000 году стала сигналом разве что для Беларуси: та пошла на такой же шаг спустя два месяца. А, например, дружественное России сирийское руководство до сих пор ДВЗЯИ даже не подписало.

При этом у Москвы не возникает вопросов к заявлениям китайских чиновников, что Пекин последует за США в деле ратификации договора. Хотя никаких гарантий нет. Напротив, Китай был бы только рад выходу из ДВЗЯИ других участников. До подписания договора Пекин успел провести только 45 ядерных испытаний — в 23 раза меньше, чем Вашингтон. На тот момент по техническому оснащению Китай уступал двум ведущим ядерным державам, поэтому не смог создать хорошую испытательную базу для моделирования испытаний. Сейчас китайцы активно увеличивают свой ядерный арсенал и были бы рады любому поводу для практической проверки новейших разработок.

Любопытно, что Россия ранее высказывала заинтересованность в том, чтобы согласовать с Китаем меры по обеспечению взаимной прозрачности полигонов. Однако китайцев это предложение не заинтересовало. Тем не менее Москва не критикует по этому поводу Пекин и не беспокоится о перспективах ядерных испытаний на территории Китая.

То есть вопрос явно не в паритете с США. Тем более что в сентябре 2023 года, по сообщениям СМИ, Соединенные Штаты предлагали представителям РФ и КНР присутствовать на субкритических испытаниях — таких, при которых не возникает условий для самоподдерживающейся цепной ядерной реакции. Подобные действия не запрещены ДВЗЯИ. Цель инициативы — доказать, что мораторий на полноценные испытания не нарушается (хотя ДВЗЯИ и не вступил в силу, обладающие ядерным оружием страны взяли на себя добровольные обязательства на этот счет).

Однако позитивной реакции со стороны РФ не последовало. Замглавы МИД Сергей Рябков, например, утверждал, что Москва сейчас в целом не намерена обсуждать с США контроль над вооружениями. Ранее в качестве условия для переговоров по подобным вопросам российские власти выдвигали изменение политики США в отношении Украины. Из этого можно сделать вывод, что и ДВЗЯИ стал жертвой войны: Россия поместила судьбу договора на лестницу эскалации, чтобы добиться уступок по Украине.

Решение дератифицировать ДВЗЯИ может обрадовать союзников России — например, Северную Корею и Иран, которые заинтересованы в свободном развитии своих ядерных программ. Но также это выгодно США и Китаю, для которых испытания еще важнее. Суть ДВЗЯИ в том, что запрет на ядерные испытания ограничивает возможность обойти количественные ограничения за счет качественного улучшения ядерного оружия. Россия между тем уже почти завершила модернизацию своих ядерных сил: создала, по словам Путина, сверхтяжелую межконтинентальную баллистическую ракету «Сармат», испытала крылатую ракету «Буревестник». И казалось бы: чтобы не облегчать жизнь другим, Москва как никто должна быть заинтересована в сохранении ДВЗЯИ. Но иные мотивы тут оказались важнее.

Баланс решения

Отзыв ратификации договора не принесет России никаких плюсов. Безопасность страны не усилится, а США на какие-то уступки в связи с этим шагом не пойдут. Единственное, чего добьется Россия — представит себя в невыгодном свете перед теми партнерами, которые у нее еще остались. До сих пор она воспринималась как важный игрок в деле ядерного нераспространения. Еще недавно МИД называл ДВЗЯИ важнейшим международно-правовым инструментом, призванным поставить надежный заслон качественному совершенствованию ядерного оружия и его расползанию по миру.

Теперь же приоритет российской политики изменился: Москва говорит миру, что ядерное нераспространение для нее не важно. Главное — это борьба с США. Возможно, скоро начнутся и дискуссии о целесообразности другого ключевого международного соглашения — Договора о нераспространении ядерного оружия (ДНЯО). С точки зрения некоторых российских ястребов, стабильный мир — это мир с ядерным оружием. Чтобы добиться мира и насолить США, ядерное оружие должно быть у многих, говорят такие эксперты.

Еще хуже будет, если отзыв ратификации станет первым шагом к ядерным испытаниям на территории РФ. Путин отмечал, что «пока достаточно будет вести себя зеркально по отношению к нашим противникам, США или другим». Однако тут важно это «пока». Президент Курчатовского института Михаил Ковальчук — близкий к президенту человек — уже призывает к ядерным испытаниям, чтобы все встало на свои места в отношениях с Западом. При таком варианте все остальные страны тоже получат моральное право на возобновление испытаний. И остановить цепную ядерную реакцию будет очень нелегко.